- Home

- About the Journal

- Peer Review

- Editorial Board

- For Authors

- Reviewer Recognition

- Archive

- Contact

- Impressum

- EWG e.V.

Cite as: Archiv EuroMedica. 2025. 15; 6. DOI 10.35630/2025/15/Iss.6.609

Background: Migraine is a common disabling neurological disorder that disproportionately affects women of reproductive age. Pregnancy complicates management because therapeutic decisions must balance maternal wellbeing with fetal and neonatal safety, requiring individualized risk assessment.

Aims: To summarize recent evidence on nonpharmacological and pharmacological approaches to migraine treatment during pregnancy with specific attention to maternal safety obstetric outcomes and child health.

Methods: This narrative review is based on a structured search of PubMed MEDLINE Embase and the Cochrane Library using pregnancy related and migraine related keywords. Priority was given to recent peer reviewed evidence. A total of 170 records were screened and 79 sources were included.

Results: Evidence in pregnant women remains limited. Nonpharmacological strategies are central to management and show benefit across behavioral therapies physiotherapy exercise relaxation and selected neuromodulation methods though heterogeneous study designs limit generalizability. Pharmacotherapy requires trimester specific evaluation. Paracetamol is the preferred drug. NSAIDs may be used briefly in mid pregnancy but should be avoided after 20 weeks. Sumatriptan has the most reassuring pregnancy data among triptans. Intravenous magnesium and short corticosteroid courses may be considered for severe attacks. Several drug classes including ergot derivatives valproate topiramate opioids metamizole and agents targeting the CGRP pathway are not suitable in pregnancy because of safety concerns or insufficient evidence. Preventive therapy may include beta blockers or amitriptyline with onabotulinumtoxinA reserved for selected refractory cases.

Conclusion: Management of migraine in pregnancy relies on prioritizing nonpharmacological interventions and applying pharmacotherapy cautiously with regard to gestational timing and clinical necessity. Current evidence remains limited underscoring the need for well designed prospective studies and pregnancy registries.

Keywords: Migraine, pregnancy, pharmacotherapy, nonpharmacological treatment, maternal safety, obstetric outcomes

Migraine is not a benign condition and, particularly when accompanied by aura, is associated with increased cardio and cerebrovascular risk [77,78]. Although most women with preexisting migraine report an improvement in symptoms during pregnancy, substantial evidence indicates that migraine adversely affects pregnancy outcomes, including a higher risk of preeclampsia and miscarriage [58].

In addition, many medications used for migraine treatment are not approved for use in pregnancy and some are associated with an increased risk of teratogenic effects [79].

Nevertheless, some women still require treatment during pregnancy to control symptoms and prevent attacks, although therapeutic options remain limited. This review examines the risks associated with migraine and the approaches to migraine management during pregnancy. It is important to discuss these risks with patients and incorporate them into clinical decision making throughout pregnancy.

Migraine is a widespread neurovascular disorder that disproportionately affects women, particularly those of reproductive age, with female-to-male ratio of approximately 2:1 to 3:1. Women not only experience a higher incidence of migraine but also report more severe associated symptoms, including photophobia, nausea, vomiting, and aura. Furthermore, women exhibit greater functional impairment during attacks, and they are more likely to be diagnosed with headache-related disability [1]. These sex differences in incidence and severity are related to hormonal fluctuations, particularly changes in estrogen levels [2,3]. A decline in estrogen is considered a principal mechanism underlying menstrual migraine and the postpartum recurrence of migraine. Accordingly, many pregnant women experience improvement in pregnancy and breastfeeding, likely due to sustained high estrogen concentrations.

However, a subset continues to suffer or develops new-onset migraine during these periods [3]. Maintaining quality of life in this population requires individualized therapeutic strategies. Pharmacotherapy remains the primary modality for migraine management; however, its use in pregnancy is complicated by concerns regarding maternal and fetal safety, and by limited clinical trial data. The objective of this literature review is to synthesize the latest evidence on migraine pharmacotherapy, with emphasis on the safety and efficacy of treatments for pregnant women.

Migraine is a prevalent, disabling primary headache disorder defined by the International Classification of Headache Disorders, 3rd edition (ICHD-3) as recurrent attacks of moderate to severe headache with characteristic associated symptoms, including photophobia, phonophobia, nausea, and vomiting. Given that approximately one-third of patients experience transient neurological disturbances termed aura, the disorder is subdivided into migraine with aura and migraine without aura [4].

According to contemporary models, migraine is considered as a neurovascular network disorder involving genetically determined neuronal hyperactivity, as well as activation and sensitization of the trigeminovascular system. The release of vasoactive, pro-nociceptive neuropeptides, particularly calcitonin gene-related peptide (CGRP), from perivascular afferents, leads to meningeal neurogenic inflammation and central sensitization within brainstem and thalamocortical nociceptive circuits [5,6]. Neuroimaging demonstrates dynamic preictal and ictal engagement of brainstem and hypothalamic nuclei that regulate homeostasis, vigilance, and autonomic control, consistent with prodromal symptoms and the heterogeneous clinical manifestations of attacks [7]. Beyond CGRP, pituitary adenylate cyclase-activating polypeptide (PACAP-38) has emerged as an additional mediator capable of provoking migraine-like attacks, highlighting convergence across neuropeptide-mediated pathways [8].

Estradiol, progesterone, and allopregnanolone, the neuroactive metabolite of progesterone, modulate critical mechanisms relevant to migraine. Abrupt estradiol withdrawal is implicated as a precipitant of attacks, whereas higher and more stable estradiol levels are associated with higher pain thresholds and attenuation of neurogenic inflammation [5,9]. Progesterone and allopregnanolone enhance GABAergic inhibition and stabilize cortical excitability [10,11]. Interactions between reproductive hormones and neural circuits underlie the female predominance and cyclical patterns of migraine expression. During pregnancy, estradiol and progesterone concentrations rise in early gestation and reach high levels that are sustained throughout the second and third trimesters. Many women with preexisting migraine, particularly without aura, experience fewer and less intense attacks. However, improvement is not consistent across patients, and a subset experiences persistence or exacerbation. Moreover, migraine attacks, sometimes with aura, may manifest de novo during gestation. In the early postpartum period, the abrupt decline in estrogen concentrations frequently coincides with recurrence of attacks [12,13].

Physiologic vascular adaptations in pregnancy provide additional context for how migraine manifests during gestation. CGRP is a potent vasodilator that contributes to maternal systemic and uteroplacental hemodynamics, lowering uterine vascular resistance and supporting placental perfusion. This duality, pathogenic in migraine yet physiologically essential for uteroplacental blood flow, highlights the connection between migraine pathophysiology and pregnancy [14]. Although pharmacovigilance analyses of anti-CGRP agents used off-label in pregnancy have not revealed disproportionate safety signals, caution remains warranted given CGRP’s homeostatic roles and incomplete outcome data [15]. Observational studies associate migraine to adverse obstetric outcomes, including hypertensive disorders of pregnancy and preterm birth, as well as an increased risk of maternal stroke, particularly among women with aura, although absolute risks remain low and causality is unproven [12,16,17].

To synthesize recent evidence on nonpharmacological and pharmacological treatment strategies for migraine in pregnancy, with attention to maternal safety, obstetric outcomes, and child health.

This study was conducted as a narrative literature review aimed at synthesizing contemporary evidence on nonpharmacological and pharmacological management of migraine in pregnancy. A narrative design was selected because the available literature is heterogeneous in methodology, incorporates clinical guidelines, mechanistic studies, observational cohorts, pharmacovigilance analyses, and a limited number of randomized trials, and therefore does not permit formal meta analytic synthesis.

A structured literature search was performed in PubMed MEDLINE Embase and the Cochrane Library. Search terms combined migraine related and pregnancy related keywords and included variations for acute treatment preventive therapy pharmacovigilance maternal outcomes fetal outcomes and obstetric complications. The search covered all years available in the databases and prioritized publications from the last ten years while incorporating earlier articles when required for mechanistic or historical context.

All retrieved records underwent a two stage screening process consisting of title abstract review followed by full text assessment. A total of 170 publications were screened. After evaluation of clinical relevance and data interpretability 79 peer reviewed sources were included in the final synthesis.

Inclusion criteria consisted of peer reviewed clinical guidelines systematic reviews meta analyses randomized or observational studies pharmacovigilance reports and case series that provided clinically interpretable data on migraine in pregnancy or postpartum including maternal safety pharmacological or nonpharmacological treatment fetal or neonatal outcomes and obstetric endpoints.

Exclusion criteria consisted of studies without relevance to migraine in pregnancy conference abstracts lacking extractable data preclinical research papers with no clinical applicability duplicated analyses from the same cohort and articles without clinically interpretable outcomes.

Given the narrative design no formal risk of bias scoring or quantitative pooling was performed. Evidence was integrated descriptively with attention to trimester specific safety management strategies maternal adverse effects fetal and neonatal outcomes and principal obstetric complications.

Pregnancy is an exceptional time in a woman’s life that requires caution from healthcare providers when prescribing medications. Consideration must be given not only to maternal health, but also to the transplacental passage of pharmacological agents and their potential teratogenic effects on the fetus. In 2015, The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) replaced its letter-based drug safety classification system in pregnancy with the Pregnancy and Lactation Labeling Rule (PLLR). The PLLR provides both clinicians and patients with more detailed, narrative risk-benefit information, not only for use during pregnancy and lactation, but also concerning its influence on female and male reproductive potential [18]. Before initiating treatment in a pregnant woman, healthcare providers are required to review the safety profile of each medication and to counsel patients regarding possible adverse drug reactions.

According to the current guidelines of the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG), nonpharmacological interventions are recommended as first-line approaches to migraine prevention in pregnancy. These include lifestyle modifications that are unlikely to cause harm, such as identifying and avoiding individual triggering factors and maintaining adequate hydration [19]. Studies have demonstrated a correlation between sleep disturbances and migraine incidence, highlighting the significance of optimizing sleep hygiene. Inadequate sleep quality, irregular sleep patterns, sleep deprivation and oversleeping have all been implicated in the increased frequency and intensity of migraine attacks. Therefore, adhering to a consistent sleep-wake up schedule with adequate duration and quality is considered an essential preventive measure [20,21].

Additionally, behavioral interventions have an increasingly robust evidence base. Relaxation techniques and cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT), including stress reduction based on mindfulness techniques and guided meditation, have been shown to reduce the clinical burden of migraine. These interventions not only alleviate stress and anxiety, which are well-recognized migraine exacerbating factors, but also contribute to improved sleep regulation [22-24]. In a randomized clinical trial involving 98 adults with migraine, the majority of whom were women (mean age approximately 43 years), mindfulness-based stress reduction did not reduce attack frequency more than structured headache education. However, over 3-9 months of follow-up period, it significantly improved disability, quality of life, self-efficacy, pain catastrophizing, mood, and experimental pain sensitivity [25]. These outcomes are particularly relevant in pregnancy when pharmacologic options are limited. Recent reviews focused on headaches during pregnancy and the postpartum period emphasize behavioral interventions as low-risk, reasonable first-line options, while underscoring the need for randomized clinical trials in this population [24].

Physical therapy and low-impact exercises, such as yoga, swimming, or walking, have also emerged as promising interventions for migraine management during gestation, given their favorable safety profile. In a randomized clinical trial including 60 pregnant women with migraine, three nonpharmacological approaches were implemented over an eight-week period. Evidence demonstrated that physiotherapy and exercise, as well as relaxation techniques, reduced attack frequency, intensity, and duration, while also improving sleep and quality of life [22]. These findings are supported by recent systematic reviews and clinical guidelines in the general migraine population, which emphasize moderate-intensity aerobic exercise and yoga as the most effective modalities for decreasing migraine frequency, severity, and disability [26,27]. Although evidence in pregnant women remains limited, the overall consistency of results supports recommending appropriately individualized physical activity as first-line interventions. Particularly, data from a cohort study including more than 90,000 pregnant women, found that women with migraine were significantly less likely to achieve recommended levels of physical activity in early pregnancy compared with those without migraine, emphasizing the importance of targeted counseling and individualized exercise plans [28].

Acupuncture and biofeedback may be considered as low-risk nonpharmacological options for migraine management during pregnancy. Current obstetric guidance notes limited evidence for safety and efficacy in pregnant patients, warranting the need for further investigation [19]. Limited observational findings suggest feasibility and reassuring safety: in a retrospective cohort of 68 pregnant women with migraine who underwent a standardized acupuncture protocol, no statistically significant differences were observed in gestational age or preterm birth, and adverse effects were mild and transient, such as local pain or paresthesia [29,30]. However, the limited number of participants and retrospective design restrict the applicability of these results. Pregnancy-specific trials for safety and efficacy of biofeedback remain limited, however, reviews focused on pregnancy and lactation describe it only as a reasonable, low-risk behavioral adjunct, while emphasizing the need for well-designed randomized studies to define efficacy in this population [24]. In clinical practice, these modalities should therefore be introduced through shared decision as experimental adjuncts to first-line lifestyle and behavioral strategies, delivered by trained practitioners and tailored to individual patient preferences and obstetric considerations.

Noninvasive neuromodulation, such as trigeminal nerve stimulation, has emerged as a promising nonpharmacological option for the management of migraine. Nonetheless, evidence remains preliminary, and further studies are required to confirm its efficacy [31]. Its use during pregnancy is not routinely recommended, as its safety has not yet been sufficiently established in this population [19]. Preliminary pregnancy-specific data exist for remote electrical neuromodulation (REN): a retrospective, controlled survey reported no increase in adverse outcomes among pregnant REN users compared with a control group, supporting a reassuring safety signal but not establishing effectiveness in migraine management during pregnancy [22]. A recent review on neuromodulation in pregnancy likewise concludes that safety and efficacy data in pregnant patients is limited across modalities, and emphasizes the need for prospective trials before routine use can be recommended [33].

Overall, nonpharmacological interventions represent a valuable first-line approach for migraine management in pregnancy, offering an alternative strategy to pharmacological treatment while minimizing fetal exposure. Further well-designed clinical trials are essential to strengthen the evidence base and refine recommendations for their application in obstetric care.

When nonpharmacological methods are insufficient, consideration must be given to implementing pharmacological treatment. In pregnancy, medication choices should be individualized by trimester, attack severity, comorbidities, and prior response, using the lowest effective dose for the shortest necessary duration. Decisions should be made with the involvement of the pregnant women and with periodic reassessment. As presented in Summary Table 1, several migraine medications are associated with fetal risks and are therefore contraindicated or may be considered safe only during specific trimesters of pregnancy. The ACOG clinical guideline endorses a stepwise strategy that prioritizes drugs with the most favorable obstetric safety evidence, escalates cautiously when attacks remain resistant, and requires evaluation for secondary causes when warning signs or clinical context suggest a nonprimary etiology [19].

Summary Table 1. Pharmacological migraine management in pregnancy

| Class/drug | Role | Trimester consideration | Key cautions |

| Paracetamol (acetaminophen) | First-line option | All trimesters | Use intermittently at the lowest effective dose; ongoing debate on long-term neurodevelopmental outcomes [34-42] |

| Caffeine (≤200 mg/day) | Adjunct | All trimesters | Avoid later in the day to limit sleep disruption [43-45] |

| NSAIDs (e.g., ibuprofen, naproxen) | Consider when first-line option inadequate | Avoid routine use ≥20 weeks’ gestation; contraindicated in 3rd trimester | Fetal renal dysfunction, oligohydramnios; ductus arteriosus constriction, neonatal pulmonary hypertension [19], [46-50] |

| Triptans (especially sumatriptan) | Consider when first-line option inadequate | All trimesters | Mixed signals for miscarriage in one cohort with notable limitations [19], [56-58] |

| Antiemetics (e.g., metoclopramide ± diphenhydramine; prochlorperazine/promethazine; ondansetron) | Control nausea and vomiting, facilitate oral therapy | All trimesters | Extrapyramidal symptoms/sedation with dopamine antagonists; ondansetron as second-line when needed [19] |

| Intravenous magnesium sulfate | Consider for aura/status migrainosus | Short, targeted exposure | Differentiate from prolonged obstetric regimens [19] |

| Systemic corticosteroids (e.g., prednisone) | Short course for refractory status migrainosus | Prefer to avoid in 1st trimester | Epidemiological reports for orofacial clefts with early systemic exposure [19], [62] |

| Metamizole (dipyrone) | Reserve to use only if alternatives unsuitable | Avoid especially in 3rd trimester | Oligohydramnios; ductus arteriosus constriction; agranulocytosis [48], [53-55] |

| β-blockers (metoprolol, propranolol) | Migraine attacks prevention | All trimesters | Possible small-for-gestational-age, consider fetal growth assessment in the 3rd trimester [19], [68-69] |

| Amitriptyline | Alternative first-line for prevention [19] | All trimesters | |

| OnabotulinumtoxinA | Refractory cases after counseling [73-76] | All trimesters | |

| Ergot derivatives (ergotamine, dihydroergotamine) | Contraindicated | - | Uteroplacental perfusion reduction, prematurity [19], [56] |

| Valproate | Contraindicated | - | Teratogenicity, adverse neurodevelopmental outcomes [19], [66] |

| Topiramate | Should be avoided | - | Increased risk of congenital malformations, fetal growth restriction [19], [67] |

| Opioids | Should be avoided | - | Limited efficacy, neonatal opioid withdrawal syndrome [19], [68-70] |

| CGRP-pathway agents | Not recommended | - | Insufficient evidence of safety [15], [19], [63-65] |

NSAID - Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, CGRP - Calcitonin gene-related peptide

Paracetamol (acetaminophen) remains a first-line option for mild-to-moderate attacks in pregnancy and may serve as a foundation to which adjuncts are added for more severe pain. In September 2025, the U.S. FDA initiated a change to acetaminophen product labeling to note a possible association between use during pregnancy and neurodevelopmental outcomes in the fetus [34,35]. Concerns remain unresolved - although some observational analyses report associations between prenatal exposure and later attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) or autism spectrum disorder (ASD), including cohorts using cord-blood biomarkers and meconium assays [36,37], a large Swedish cohort with sibling-control analyses (N=2,480,797 children; 185,909 [7.49%] exposed) found no associations once shared familial factors were accounted for (HR for autism 0.98, ADHD 0.98, intellectual disability 1.01). These findings suggest that reported associations may reflect indication and shared environmental, as well as genetic factors rather than a drug effect [38]. In addition to the ACOG guidance, the Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (RCOG) and the European Medicines Agency (EMA) advise that paracetamol should be used when clinically indicated, at the lowest effective dose for the shortest duration [39-42].

Caffeine can be used as an adjunct (e.g., in combination products), although total daily intake should adhere to obstetric guidance and must not exceed 200 mg/day, with all dietary and medicinal sources considered [43]. Cohort data indicate small reductions in neonatal size and subtle differences in childhood growth even at low intakes. Although the clinical significance of these findings remains uncertain, they support a restrained intake limit and avoidance of excess [44,45]. To minimize sleep disruption, a recognized migraine trigger, adjunctive caffeine should generally be avoided later in the day.

Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), e.g., ibuprofen or naproxen, may be used carefully when paracetamol is inadequate, but gestational timing is critical. Obstetric guidance emphasizes trimester-specific precautions for the prostaglandin-synthesis inhibitors [19]. Routine use from 20 weeks’ gestation onward should be avoided because of fetal renal dysfunction leading to oligohydramnios. If treatment between 20 and 30 weeks’ gestation is necessary, therapy should be restricted to the lowest effective dose for the shortest possible course; exposures longer than 48 hours warrant consideration of ultrasound assessment of amniotic fluid. In the third trimester, NSAIDs are contraindicated owing to the risk of premature ductus arteriosus constriction with potential neonatal pulmonary hypertension [46-49]. Emerging population-based data also suggest potential adverse renal outcomes in offspring following gestational NSAID exposure, reinforcing cautious, time-limited use and preference for non-NSAID options whenever feasible [50]. An exception is low-dose aspirin for preeclampsia prophylaxis under obstetric supervision, which is not subject to these restrictions [19, 51, 52].

Metamizole (dipyrone) is a non-opioid analgesic with established use in several European countries, yet it is unavailable in the United States. Exposure in second and in third trimesters has been associated with oligohydramnios and prenatal ductus arteriosus constriction, supporting avoidance in pregnancy [48]. A recent systematic review judged the evidence insufficient to define teratogenic risk, noting that most included studies did not show an association, but overall risk of bias was high [53]. A subsequent systematic review and meta-analysis likewise reported no association between maternal metamizole exposure and several offspring outcomes (e.g., congenital anomalies, pregnancy loss), while grading the certainty of evidence as low to very low and cautioning against interfering safety [54]. From the maternal safety perspective, metamizole-induced agranulocytosis remains a rare but serious idiosyncratic reaction; recent syntheses and population-based analyses confirm that risk is not negligible, with signals suggesting higher rates than with some alternative analgesics [55]. These data support restricting metamizole to situations in which alternatives are unsuitable, with careful clinical monitoring when exposure occurs later in gestation.

For acute migraine attacks unresponsive to nonpharmacological strategies and paracetamol, triptans may be considered. Sumatriptan is preferred, given the most extensive pregnancy data [19]. In a large, observational cohort, based on U.S. administrative claims (2011-2021), gestational triptan exposure was not associated with prematurity, low birth weight, major congenital malformations, or clinically detected spontaneous abortion after adjustment for confounding [56]. Neurodevelopmental follow-up likewise suggests no increased risk of ADHD among offspring with prenatal triptan exposure [57]. A recent meta-analytic synthesis found higher odds of miscarriage among pregnancies exposed to triptan compared with women without migraine, highlighting the importance of comparator selection and the potential residual confounding. The same review reaffirmed that migraine itself is associated with adverse obstetric outcomes, including preeclampsia and preterm birth [58]. Recent narrative syntheses integrating registry and cohort data conclude that measured, intermittent triptan use, particularly sumatriptan, can be appropriate in pregnancy when attacks are refractory to first-line options [12].

For acute migraine with prominent nausea or vomiting, antiemetics may be co-administrated with analgesics to improve symptom control and oral tolerance. ACOG supports the use of metoclopramide, a dopamine-antagonist drug. Diphenhydramine is commonly added to mitigate metoclopramide-related akathisia [19]. Metoclopramide exposure in first trimester has not been associated with major congenital malformations in meta-analysis [59]. For ondansetron, recent cohort data reported no increased risk of overall major congenital anomalies or clinically important cardiac defects with pregnancy exposure. Nevertheless, differences in study design and exposure assessment limit certainty, so use should be reserved for situations in which first-line options are insufficient [60]. Therapy based on antihistamine drugs remains a reasonable option for nausea and vomiting in pregnancy and is considered compatible with gestation recent reviews [61].

Intravenous magnesium sulfate may be considered for aura-predominant attacks or status migrainosus. If used, exposure should be brief and distinguished from prolonged obstetric regimens for hypertensive disorders [19]. Short courses of systemic corticosteroids (e.g., prednisone) may be considered for refractory status migrainosus; however, many clinicians avoid first-trimester systemic regimens owing to signals of a slight increase in orofacial clefts with early-pregnancy exposure [19, 62].

Given the physiological role of CGRP in gestational vascular adaption and uteroplacental perfusion, use of CGRP monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) and gepants during pregnancy is not recommended. ACOG advises discontinuation when pregnancy is planned or recognized and selection of alternative therapies [19]. Pharmacovigilance analyses and periconception case series have not shown a consistent pattern of adverse outcomes. However, the evidence is limited by the low number of exposed pregnancies, brief early exposures, and reporting limitations, and therefore does not establish safety [15, 63]. Expert consensus statements recommend avoiding CGRP-pathway agents during pregnancy until definitive human evidence is available [64, 65].

Ergot derivatives (ergotamine, dihydroergotamine) are contraindicated because potent vasoconstriction may reduce uteroplacental perfusion. Clinical guidance and cohort analyses associate gestational exposure with adverse outcomes, including prematurity [19, 56]. Valproate is likewise contraindicated for migraine treatment during pregnancy owing to documented teratogenicity and adverse neurodevelopmental outcomes [19, 66]. Topiramate, used for migraine prophylaxis, is listed among drugs to avoid during pregnancy in recent international practice recommendations, given increased risks of congenital malformations, e.g., oral clefts, and fetal growth restriction [19, 67]. Opioids are not recommended, given limited efficacy for migraine treatment, risk of headache caused by medication overuse, and perinatal adverse outcomes, including neonatal opioid withdrawal syndrome [19, 68-70].

When migraine attacks are frequent or disabling despite optimized management, preventive medication may be warranted. ACOG lists β-blockers, preferably propranolol or metoprolol, and amitriptyline as reasonable options during pregnancy, using the lowest effective dose with periodic obstetric reassessment [19, 58]. Observational data from maternal cardiovascular cohorts show a dose-related association between β-blockers and small-for-gestational-age birth, underscoring the need for dosing adjusted by trimester and for fetal growth monitoring in the third trimester when migraine prevention is necessary [68, 69]. A recent cohort study reported no significant difference in mean fetal heart rate among pregnancies exposed to maternal β-blocker therapy compared with unexposed controls [70]. In refractory cases, onabotulinumtoxin A may be continued or considered after individualized counseling. A 29-year cumulative safety update and case series did not show an excess of major congenital malformations, although the evidence remains observational with limited data [73-76].

Available evidence on the treatment of migraine during pregnancy remains fragmented and heterogeneous, which limits the strength of clinical conclusions [2,3,12,19,58]. Most recommendations rely on observational studies with a high likelihood of systematic bias [12,16,19,58]. Randomized controlled trials are extremely scarce due to ethical constraints, so the safety and effectiveness of many interventions are assessed indirectly [19,31,68].

Nonpharmacological approaches demonstrate the most reassuring safety profile, although the volume of data derived specifically from pregnant women is limited [19,22,24,28]. Studies involving pregnant patients generally include small samples, vary in design, and evaluate different clinical endpoints [22,29,30,32,33]. Even with these limitations, research on physiotherapy, relaxation methods, cognitive behavioral therapy, and exercise shows reductions in attack frequency and severity as well as improvements in quality of life [22,23,25 27]. A major limitation remains the lack of standardized protocols and long term follow up, which hinders the development of stronger evidence based recommendations [24,26,33].

Pharmacotherapy requires strict trimester specific individualization. Paracetamol remains the most widely studied agent, yet its safety continues to be debated due to emerging data on potential neurodevelopmental effects based on biomarker and epidemiological studies [34 38]. Large cohort studies and regulatory authorities emphasize that paracetamol should be used only when clinically indicated, at the lowest effective dose, and for the shortest duration required [39 42]. Evidence regarding nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs underscores the critical importance of gestational age, as potential complications such as oligohydramnios, fetal renal dysfunction, and premature ductus arteriosus constriction are directly dependent on exposure timing [46 50]. Triptans are considered an acceptable option when first line therapy is insufficient, with sumatriptan having the most favorable pregnancy specific safety profile and no demonstrated increase in major congenital anomalies or severe perinatal complications with intermittent use [56 58,68]. In contrast, several migraine specific medications including ergot derivatives, valproate, topiramate, opioids, and CGRP pathway agents cannot be recommended during pregnancy due to known teratogenic and perinatal risks or insufficient human safety data [15,31,63 67,69,70,79].

Preventive therapy is also significantly limited. Beta blockers and amitriptyline remain primary options but require individualized risk assessment including potential effects on fetal growth, hemodynamics, and the need for monitoring in late gestation [19,68,71 73]. Data on the use of onabotulinumtoxinA in pregnancy come from registries and observational series which, although not demonstrating a clear increase in major congenital anomalies or other serious adverse outcomes, are insufficient to draw definitive safety conclusions due to sample size and study design [74 76].

A major limitation of the existing literature is the lack of uniformity in safety assessment. Observational studies rarely fully account for migraine severity, disease duration, prior treatments, comorbidities, and behavioral factors [12,16,58]. In many analyses risks attributed to medications may reflect the underlying disease itself, since migraine is independently associated with increased rates of hypertensive disorders, preeclampsia, preterm birth, and vascular events during pregnancy [12,16,17,58,77]. This complicates the interpretation of causal relationships and may lead to overestimation of medication related risks.

Overall, available data support the need for individualized treatment planning prioritizing nonpharmacological strategies and cautious use of medications based on trimester, symptom severity, and obstetric risk [19,22,24,58,68]. Large prospective studies and dedicated pregnancy registries are required to more precisely characterize the risks of specific interventions and to inform more detailed and reliable clinical recommendations [58,68,79].

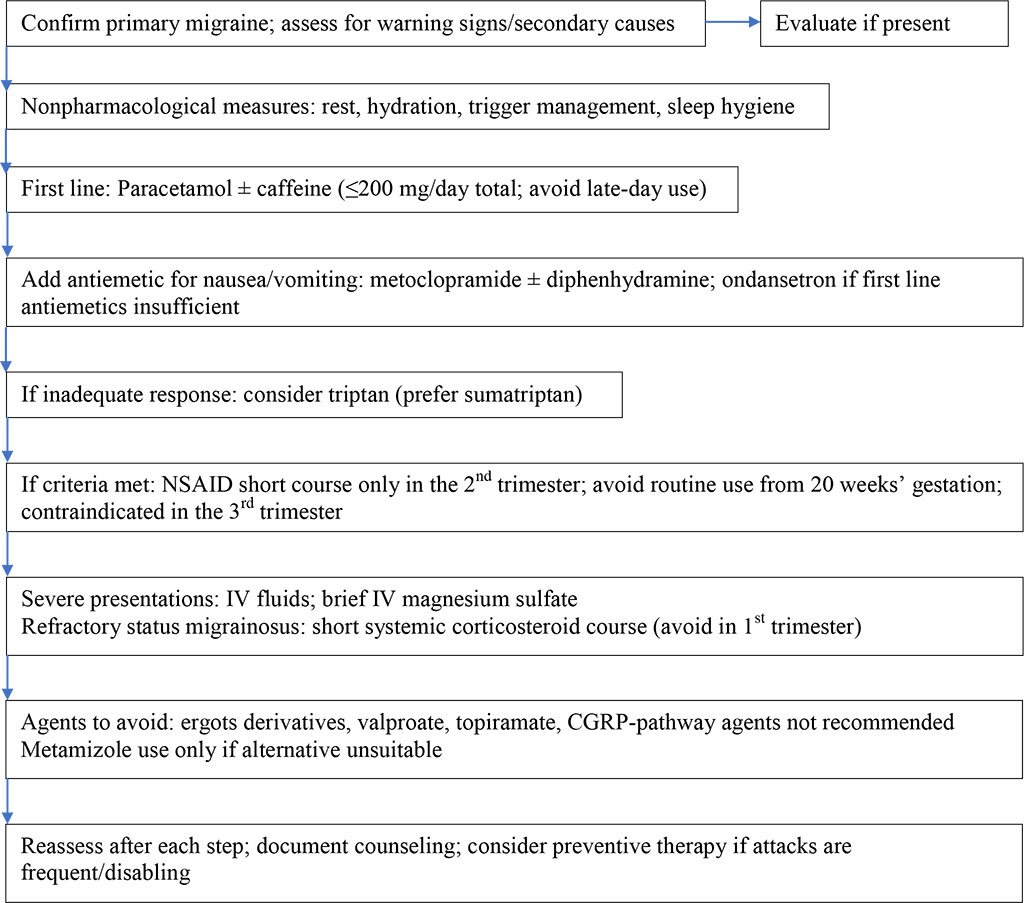

As summarized in Figure 1, management of migraine during pregnancy should prioritize the safest evidence-based approaches that minimize potential fetal impact. Escalation to subsequent treatment steps should be considered only if symptoms persist despite the initial intervention.

Figure 1. Stepwise migraine management in pregnancy

Migraine management in pregnancy requires an approach that aligns with the aims of this review and remains consistent with the available evidence. The synthesis of 80 included sources shows that therapeutic decisions must consider gestational age, maternal comorbidities and the balance between symptom control and fetal safety. Nonpharmacological interventions constitute the safest foundation of care and should be prioritized as first-line strategies whenever feasible. Their effectiveness is supported by multiple studies, although evidence specific to pregnant populations remains limited.

Pharmacological therapy is reserved for situations in which symptoms significantly impair functioning or do not respond to conservative measures. Paracetamol remains the most studied and most commonly recommended option, though its use should be intermittent and limited to the lowest effective dose in light of emerging neurodevelopmental concerns. The safety of NSAIDs depends critically on timing, and their use should be confined to early second trimester when clinically justified. Triptans, particularly sumatriptan, appear acceptable for intermittent use when first-line measures fail, based on available pregnancy data. Antiemetics may be added when needed, while intravenous magnesium sulfate and short corticosteroid courses may be considered only in refractory presentations with strict attention to trimester specific risks. Agents with known or probable teratogenicity or insufficient safety evidence including ergots valproate topiramate opioids metamizole and CGRP pathway targeted therapies should be avoided.

Preventive therapy during pregnancy remains limited to a narrow range of options, primarily beta blockers and amitriptyline, with individualized assessment and obstetric surveillance. OnabotulinumtoxinA may be considered in selected refractory cases, though current data remain insufficient for firm recommendations.

Overall, the evidence base is heterogeneous and constrained by the lack of randomized trials, small sample sizes in pregnancy specific cohorts and inconsistent reporting of migraine severity and obstetric risk factors. These limitations underscore the need for prospective studies and dedicated pregnancy registries. Until such data become available, clinical decision making must rely on individualized risk benefit assessment, prioritization of nonpharmacological methods and cautious trimester adjusted pharmacotherapy.