- Home

- About the Journal

- Peer Review

- Editorial Board

- For Authors

- Reviewer Recognition

- Archive

- Contact

- Impressum

- EWG e.V.

Cite as: Archiv EuroMedica. 2025. 15; 6. DOI 10.35630/2025/15/Iss.6.605

Background: Malnutrition in adults aged 75 years and older is a major determinant of morbidity, mortality, and reduced functional independence. Although diagnostic frameworks such as ESPEN and GLIM have improved recognition, malnutrition in this population remains underdiagnosed and undertreated.

Aim: To summarize and critically evaluate current evidence (2010–2025) on the association between malnutrition and treatment outcomes in individuals aged 75 years and older, emphasizing diagnostic criteria, prognostic implications, and the effectiveness of nutritional interventions.

Methods: A narrative review was conducted using PubMed, Scopus, Web of Science, and Clinical Nutrition databases. Forty-one studies meeting inclusion criteria were analyzed, including randomized controlled trials, cohort studies, meta-analyses, and expert guidelines.

Results: Malnutrition in the 75+ population is consistently associated with longer hospitalization, increased postoperative and infectious complications, higher readmission and mortality rates, and poorer quality of life. Diagnostic heterogeneity persists across studies, and GLIM-based definitions yield the strongest prognostic discrimination. Nutritional interventions—particularly early, multidisciplinary approaches combining oral nutritional supplementation, individualized dietetic care, and rehabilitation—improve short-term outcomes but show variable long-term benefits.

Conclusions: Malnutrition in advanced old age is a preventable and modifiable predictor of adverse clinical outcomes. Systematic screening, standardized diagnosis using ESPEN and GLIM criteria, and early implementation of comprehensive nutritional care should become integral to geriatric practice. Future research must include large, age-specific interventional trials evaluating long-term effects on survival, functional capacity, and quality of life.

Keywords: malnutrition, older adults, geriatric nutrition, GLIM criteria, ESPEN, nutritional intervention, quality of life, frailty, sarcopenia

Malnutrition is one of the key medical and social challenges in geriatric medicine and clinical nutrition. It is defined as a state of deficiency or impaired absorption of nutrients leading to changes in body composition, reduction of fat-free mass, decline in physical and cognitive performance, and increased risk of adverse treatment outcomes [1, 2]. In individuals aged 75 years and older, malnutrition is particularly common and accompanies a wide range of chronic conditions, including cardiovascular, oncological, inflammatory, and neurodegenerative diseases [3, 4]. According to international studies, the prevalence of malnutrition among hospitalized older patients reaches 40–50%, and 5–10% among those living at home [5]. The risk is higher in women due to hormonal changes, lower muscle mass, and a higher incidence of comorbidities [2, 6]. The main determinants of malnutrition in advanced age include physiological factors (reduced salivation, taste disorders, malabsorption, gastrointestinal dysfunction), psychological factors (anorexia of aging, depression, cognitive impairment), social determinants (loneliness, low income, limited access to care), and pathological processes associated with chronic inflammation or malignancy [2, 4, 7].

Malnutrition in older adults significantly worsens disease progression, increases hospital stay, raises the frequency of infectious and postoperative complications, reduces quality of life, and elevates mortality [5, 7]. At the same time, systematic diagnosis and correction of nutritional disorders in individuals over 75 years remain insufficiently implemented in clinical practice, despite the existence of international diagnostic standards such as ESPEN and GLIM, which aim to standardize the assessment and management of protein–energy deficiency [1, 9]. The relevance of the present review lies in the need to update and expand current knowledge on the impact of malnutrition on treatment outcomes in the elderly population, taking into account the latest data from 2020–2025 [5]. Unlike previous reviews covering studies up to 2019–2020 and focusing mainly on the general older population, this paper concentrates specifically on adults aged 75 years and older—a group at particularly high risk of malnutrition and its consequences [4, 7]. The novelty of this review consists in the synthesis and analysis of the most recent data on the relationship between nutritional status and hospitalization duration, mortality, functional independence, cognitive decline, and quality of life. The work integrates updated diagnostic approaches (ESPEN, GLIM) and modern clinical guidelines, extending the evidence base up to early 2025 [1, 5, 9]. Thus, the review provides a comprehensive interdisciplinary perspective on malnutrition in advanced old age and its implications for clinical outcomes, prevention of complications, and the effectiveness of therapeutic interventions [2, 3, 5].

To summarize and critically analyze current evidence on the impact of malnutrition on treatment outcomes in individuals aged 75 years and older, with a focus on diagnostic criteria, pathophysiological mechanisms, and the effectiveness of nutritional interventions in this age group.

This study was conducted as a narrative literature review summarizing and critically analyzing recent evidence on malnutrition and its clinical outcomes in individuals aged 75 years and older. The search was performed in PubMed, Scopus, Web of Science, and Clinical Nutrition databases for the period from January 2010 to February 2025. The search strategy combined free-text and MeSH terms, including malnutrition, elderly, geriatric nutrition, nutritional status, GLIM, ESPEN, hospitalization, mortality, wound healing, nutritional support, and quality of life.

Inclusion criteria comprised studies investigating populations aged 75 years and older, using validated instruments for nutritional assessment (MNA-SF, NRS-2002, SGA, GLIM), and reporting associations between malnutrition and treatment outcomes. Randomized controlled trials, cohort studies, systematic reviews, meta-analyses, and international clinical guidelines were included. Publications without clear assessment of nutritional status or outcome data were excluded.

After screening 168 records, 41 publications met the inclusion criteria. Data were synthesized narratively, with results organized into thematic sections covering diagnostic criteria, energy and protein requirements, hospitalization and mortality outcomes, wound healing, quality of life, and nutritional interventions. This approach allowed a comprehensive qualitative integration of current evidence on malnutrition in the 75+ population.

A total of 41 publications met the inclusion criteria, including randomized controlled trials, cohort studies, systematic reviews, meta-analyses, and expert consensus papers. The analyzed studies varied considerably in design, diagnostic criteria, and populations, but collectively provided consistent evidence linking malnutrition in adults aged 75 years and older with adverse clinical outcomes. Key findings concern hospitalization duration, mortality, wound healing, and the effectiveness of nutritional interventions.

The main clinical studies included in this review, with their design characteristics, populations, outcomes, and limitations, are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1. Summary of key clinical studies on malnutrition and treatment outcomes in individuals aged 75 years and older.

| No. | Author | Year | Study Design | Sample Characteristics | Main Outcomes | Limitations |

| 1. | Martínez- Escribano JA et al., | 2022 | Systematic review | Older adults, mean age>75, hospitalized | Malnutrition associated with longer hospital stay and higher mortality | Heterogeneity of diagnostic criteria |

| 2. | Lenti MV et al., | 2023 | Prospective cohort | Internal medicine inpatients, aged ≥75 | Malnutrition predicted early post-discharge mortality | Small sample size, single-center |

| 3. | Montalcini T et al., | 2015 | Observational study | Patients with minimal conscious state, aged ≥75 | Nutritional deficits correlated with higher short- term mortality | Lack of standardized assessment |

| 4. | Gazotti C et al., | 2003 | Randomized controlled trial | Hospitalized elderly, mean age 78 | Nutritional supplementation reduced complications and hospital stay | Limited follow-up period |

| 5. | Deutz NE et al., | 2014 | Expert consensus | Geriatric population | Adequate protein intake improves muscle function and outcomes | Not based on primary data |

| 6. | Cederholm T et al., | 2019 | Consensus report (GLIM) | Multicenter expert panel | Established international diagnostic criteria for malnutrition | Requires clinical validation |

Following the summary of key studies presented in Table 1, the main findings from representative clinical and consensus works are outlined below.

Martínez-Escribano and colleagues (2022) conducted a systematic review analyzing the relationship between malnutrition and treatment outcomes among older hospitalized adults, with a mean age exceeding 75 years. The review synthesized data from multiple clinical and observational studies, aiming to assess the impact of nutritional status on hospitalization parameters and mortality [24].

The findings demonstrated a consistent association between malnutrition and poorer clinical outcomes, particularly prolonged hospital stays and increased mortality rates. Malnourished patients exhibited slower recovery trajectories, higher complication rates, and greater dependency after discharge compared to well-nourished counterparts [24,25].

However, the study also emphasized significant heterogeneity in diagnostic criteria across the included research. Different assessment tools—such as the Mini Nutritional Assessment (MNA), Subjective Global Assessment (SGA), and more recent GLIM criteria—were used inconsistently, resulting in wide variability in the reported prevalence of malnutrition and its prognostic strength [22].

The authors found out that despite the strong and reproducible link between malnutrition and adverse outcomes, the lack of standardized diagnostic protocols remains a major barrier to evidence comparability and the formulation of universal clinical guidelines. They highlighted the need for further prospective studies using unified definitions, such as the GLIM framework, to better estimate the magnitude of risk and guide effective nutritional interventions in the ≥75-year-old population [22].

Lenti and colleagues [21] conducted a prospective cohort study among internal medicine inpatients aged ≥75 years to examine the prognostic role of malnutrition in early post-discharge outcomes. The study found that malnutrition was a strong independent predictor of early post-discharge mortality, underscoring the need for systematic nutritional screening during hospitalization. However, the study was limited by its small sample size and single-center design, which restricts generalizability. Despite these limitations, the findings support early nutritional assessment as a critical component of discharge planning for older adults.

Montalcini and colleagues [16] examined patients aged ≥75 years in a minimally conscious state and reported that nutritional deficits were strongly correlated with higher short-term mortality. The study emphasized the vulnerability of cognitively impaired elderly patients to malnutrition-related complications. However, the absence of standardized assessment tools for nutritional evaluation limited the precision and comparability of the results. The findings nonetheless highlight the clinical importance of nutritional monitoring even in patients with severely limited cognitive and functional capacities.

Gazotti and colleagues [26] performed a randomized controlled trial involving hospitalized elderly patients (mean age 78 years) to assess the effects of nutritional supplementation on clinical outcomes. The results demonstrated that nutritional supplementation significantly reduced the incidence of complications and shortened hospital stays, confirming the therapeutic potential of targeted nutritional interventions. Nevertheless, the study’s limited follow-up period prevented assessment of long-term benefits and sustainability of outcomes [26].

Deutz and collaborators [29] published an expert consensus summarizing evidence regarding protein requirements in the geriatric population. The consensus emphasized that adequate protein intake improves muscle functio physical recovery, and overall clinical outcomes among older adults, particularly those with frailty or chronic disease. However, since the document was not based on primary clinical data, its recommendations require further validation through prospective and interventional studies [30].

Cederholm and an international, multicenter expert panel developed the GLIM (Global Leadership Initiative on Malnutrition) criteria, establishing standardized international diagnostic guidelines for malnutrition [34]. The GLIM framework represented a major advance toward unifying clinical and research definitions of malnutrition, proposing a two-step diagnostic process that combines screening and phenotypic/etiologic assessment. However, the authors noted that clinical validation of these criteria in diverse geriatric populations—particularly in those aged ≥75 years—remains essential to ensure reliability and applicability across healthcare settings [34].

Collectively, these studies demonstrate that malnutrition in individuals aged ≥75 years significantly worsens treatment outcomes, including mortality, complication rates, and hospitalization duration. While interventional and consensus data underline the benefits of adequate nutrition and standardized diagnostic approaches, methodological limitations—such as small sample sizes, lack of long-term follow-up, and variability in assessment methods—highlight the need for large-scale, multicenter trials and validation of GLIM criteria specifically in the oldest-old population [31].

Several types of malnutrition are distinguished:

Marasmus is associated with the typical features of malnutrition. While kwashiorkor appears to have much more complex and not fully understood causes, marasmus is certainly a consequence of an inadequately balanced and deficient diet. Insufficient intake of energy and nutrients manifests as wasting, significant loss of subcutaneous fat, muscle tissue breakdown, and atrophy of most internal organs [33].

Nevertheless, the marasmus type is associated with lower mortality than edematous malnutrition. Among survivors, long-term complications include impaired cognitive function, which occurs with similar frequency in both types. In contrast, motor function problems are significantly more common in kwashiorkor [34].

Nutritional treatment is very similar for both types. The only difference is that antibiotic therapy does not improve outcomes in marasmus due to the absence of dysbiosis. For this reason, antibiotics are mainly used in clinical practice for patients with kwashiorkor [35].

According to WHO guidelines, the treatment of malnourished patients should follow 10 steps, ranked from the most urgent to the least urgent. Within the first two days, hypoglycemia, hypothermia, and dehydration should be addressed. At the same time, electrolyte deficiencies should be corrected, infections treated, and micronutrient deficiencies supplemented, except for iron. Iron supplementation is introduced only around the second week of rehabilitation [36,37].

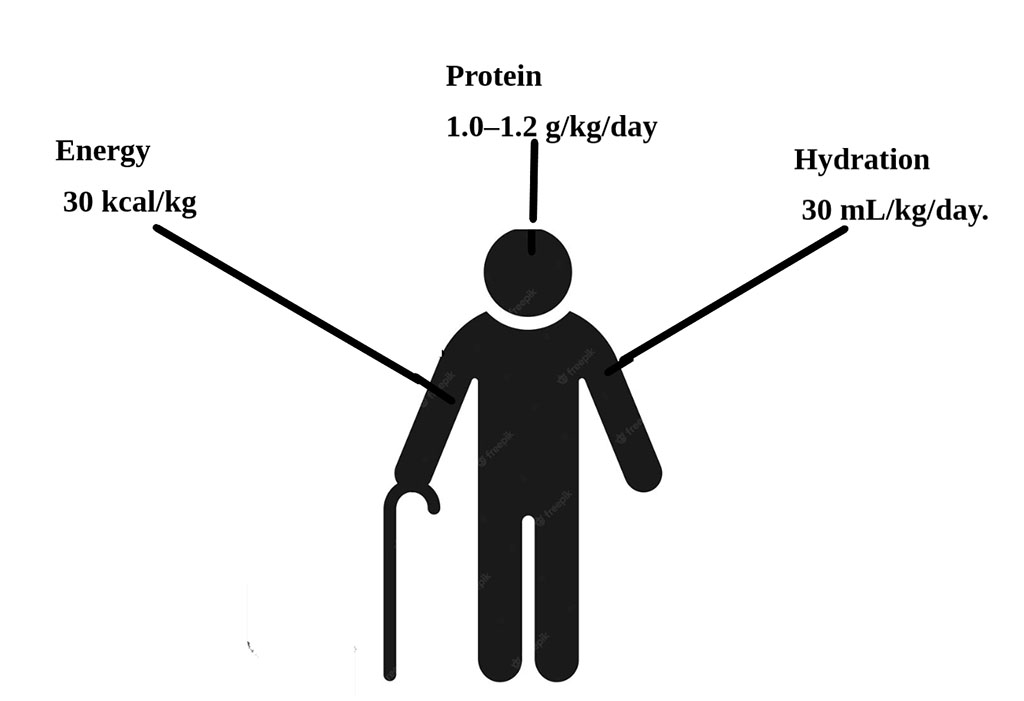

According to ESPEN guidelines (2022):

Energy intake should be approximately 30 kcal/kg body weight per day as a reference value, individualized to nutritional status, comorbidities, and activity; 32–38 kcal/kg/day for underweight individuals and 27–30 kcal/kg/day for older inpatients. Protein intake should be 1.0–1.2 g/kg/day for ill individuals or those with frailty. Hydration should be approximately 30 mL/kg/day.

With advancing age, resting energy expenditure decreases due to reductions in fat-free mass and is influenced by sex and nutritional status. In older adults, energy requirements may be lower because of reduced physical activity, yet higher due to disease-related factors such as inflammation, fever, or medication effects. A growing body of experimental and epidemiological evidence suggests that older adults may require higher protein intakes than younger populations to optimally preserve fat-free mass, physiological function, and health. Intakes of 1.2–1.5 g/kg have been suggested for older adults with chronic diseases, whereas in the presence of malnutrition, trauma, or severe illness, requirements may be up to 2 g/kg.

Older adults often suffer from gastrointestinal disorders, including constipation and diarrhea. Dietary fiber can help normalize bowel function, and its average daily intake should be about 25 g/day to achieve regular bowel movements. Based on the literature, EFSA has recommended a daily water intake of 2 L/day for women and 2.5 L/day for men at all ages. Individual fluid requirements are related to energy expenditure, water losses, and kidney function. Excessive losses caused by fever, diarrhea, vomiting, or bleeding may require additional water intake. In exceptional clinical situations, such as heart or kidney failure, fluid intake may need to be restricted.

The tools and measurements used in diagnostics should provide a comprehensive assessment of nutritional status in a simple and rapid manner, taking into account the age and health condition of the person being evaluated. Particular emphasis is placed on the use of complementary methods in nutritional assessment and on the collaboration of an interdisciplinary geriatric team.

In 2019, in the journal Clinical Nutrition, ESPEN published new three-stage diagnostic criteria for malnutrition developed by the Global Leadership Initiative on Malnutrition (GLIM), aimed at standardizing the recognition of malnutrition and qualification for nutritional intervention.

Stage one consists of screening nutritional status using tools such as NRS-2002 (Nutritional Risk Screening-2002), MNA-SF (Mini Nutritional Assessment–Short Form), SGA (Subjective Global Assessment), and MUST (Malnutrition Universal Screening Tool), which identify the risk of malnutrition. A positive screening result indicates the need for further diagnostic evaluation to confirm malnutrition.

Stage two is divided into phenotypic and etiologic criteria.

Phenotypic criteria include:

According to the GLIM group, diagnostics can be supplemented with measurements of serum albumin, prealbumin, and C-reactive protein.

Stage three is used to assess the severity of malnutrition and determines further therapeutic interventions depending on the stage of advancement. Phenotypic criteria are used to define the severity of malnutrition, while etiologic criteria are considered key to establishing standards for nutritional interventions.

According to GLIM, four groups of malnutrition are distinguished based on cause:

Malnourished patients also have longer hospital stays and higher mortality. In a study conducted in China among older patients using the NRS-2002 and MNA-SF scales, a negative effect of malnutrition on length of stay was demonstrated: patients at risk of malnutrition had a longer mean hospital stay of 13.76 days, whereas patients without risk stayed 11.51 days. A positive effect of nutritional intervention was observed in patients at risk. Based on NRS-2002 results, length of stay was 5.48 days in patients receiving nutritional support versus 6.19 days in those without; based on the MNA-SF assessment, 5.18 days versus 6.44 days in malnourished patients. Gn et al. (2021) reported a 22% increase in length of stay (adjusted incidence rate ratio 1.22; 95% CI 1.00–1.49), and Puvanesarajah et al. (2017) reported an additional 3.1 days. Similar observations of prolonged stays were made by Leandro-Merhi and de Aquino (p = 0.013) and by Martínez-Escribano et al. (2022) (14.6 vs 10.5 days, p = 0.009). Two studies also showed higher one-year mortality among malnourished patients—1.7% vs 0.2%, with an adjusted odds ratio of 6.16, and a hazard ratio of 3.08 (95% CI 1.10–8.63). In studies involving patients with a mean age from the mid- to late-seventies, these results indicate that malnutrition, rather than age per se, is the main factor determining adverse outcomes of surgical treatment.

Delirium is common in older adults admitted to hospital wards. Dehydration is a major precipitating factor, and malnutrition significantly contributes to its occurrence. Abraha et al. demonstrated that non-pharmacological nutritional interventions involving feeding and hydration significantly reduced the incidence of delirium.

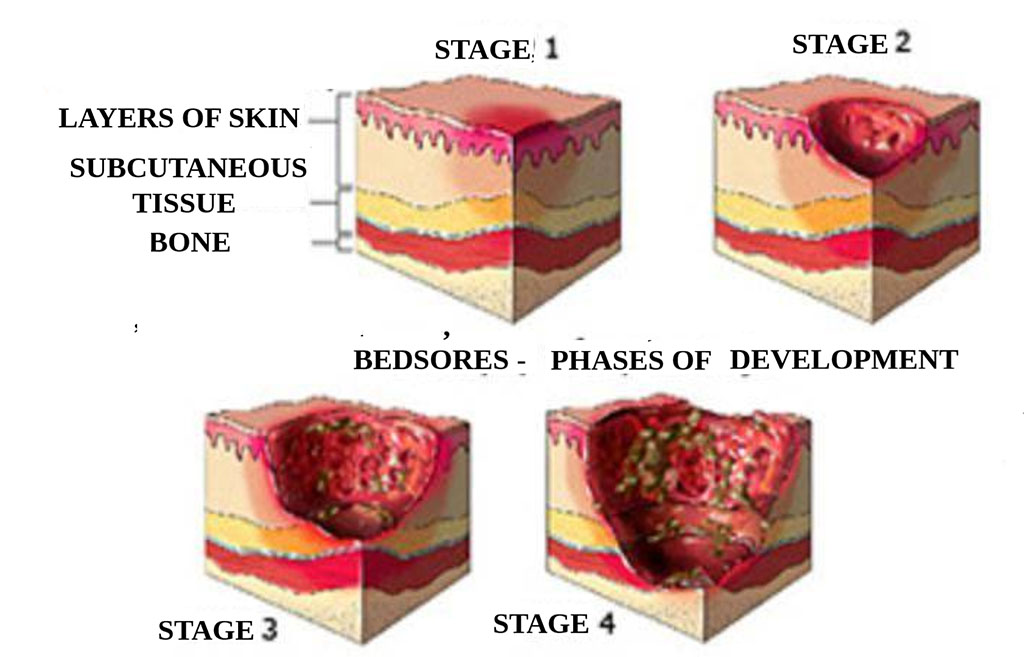

One frequent complication in the geriatric population is the development of pressure injuries, especially among bedridden patients.

Figure 1. Stages of Pressure Injury Development

It is estimated that in Europe approximately 1.5–2 million people suffer from chronic wounds, accounting for 3% of all healthcare expenditures, mainly due to the time required for care, dressings, and prolonged hospitalization [15].

Malnutrition—particularly protein-energy deficiency—and deficits of micronutrients such as zinc and vitamins C, A, and E impair collagen synthesis, angiogenesis, and the inflammatory response, adversely affecting wound healing and increasing the risk of development and progression of pressure injuries. In the study by Montalcini et al., a serum albumin level < 3.1 g/dL was associated with an increased risk of pressure injuries and with higher mortality. Proteins are the most important macronutrients for healing because they are essential for tissue repair, maintenance of a positive nitrogen balance, and all stages of wound healing, including fibroblast proliferation, collagen synthesis, angiogenesis, and immune function. For patients with stage III/IV pressure injuries, the recommended protein intake is 1.5–2 g/kg, depending on wound size. In studies, the group receiving a higher protein dose (1.8 g/kg) showed nearly double the wound-healing rate compared with the group receiving a basic intake.

Chronic pressure injuries predispose to protein loss through exudate. To prevent protein-energy malnutrition and improve wound healing, the diet should provide adequate energy in the form of carbohydrates, fats, and protein. Glucose serves as the primary energy substrate for cellular activity; therefore, enteral nutrition formulas consist mainly of carbohydrates. Fat plays a significant role in cell-membrane synthesis, serves as an energy source, and is a key component in the development of inflammatory mediators and coagulation elements. Amino acids are the building blocks of proteins. Arginine and glutamine are conditionally essential amino acids during severe stress, such as trauma, sepsis, and/or pressure injuries. Arginine stimulates insulin secretion, accelerates wound healing, and helps prevent pressure injuries. It promotes amino-acid transport into tissue cells and supports intracellular protein production. Arginine acts as a substrate for protein synthesis, cell proliferation, collagen deposition, and T-lymphocyte function, and it promotes a positive nitrogen balance. It is also a biological precursor of nitric oxide, which has potent vasodilatory, antibacterial, and angiogenic properties—each important for wound healing. In diabetes, nitric-oxide synthesis is reduced in the wound environment, and because arginine is the sole substrate for nitric-oxide synthesis, it has been hypothesized that arginine supplementation may accelerate healing by increasing nitric-oxide production. In contrast, glutamine has not been shown to have a positive effect on the healing process. In damaged, ischemic tissues, large amounts of free radicals are generated. Some micronutrients, such as vitamins A, C, and E, have antioxidant properties—they can neutralize free radicals and accelerate wound healing.

If oral intake is insufficient or not feasible, enteral or parenteral nutrition should be considered. The goal is to maintain a positive nitrogen balance, providing approximately 30–35 kcal/kg/day and 1.25–1.5 g protein/kg/day.

Vitamin A stimulates epithelialization and the immune response. It promotes monocyte and macrophage aggregation, increases their numbers in the wound, supports mucosal and epithelial surfaces, increases collagen production, and protects against the adverse effects of glucocorticoids, chemotherapy, radiotherapy, and diabetes. Vitamin A deficiency may lead to immune dysfunction, impaired collagen deposition, and delayed wound healing.

Vitamin C supports neutrophil and fibroblast activity and is essential for angiogenesis. It is a cofactor for proline and lysine hydroxylation in collagen formation. Vitamin C deficiency impairs fibroblast activity and, consequently, collagen synthesis and capillary integrity.

Copper plays a role in collagen crosslinking, which is necessary for tissue rebuilding. Manganese has tissue-regenerating roles. Zinc is an antioxidant mineral involved in the production of proteins (such as collagen), DNA and RNA, and in cell proliferation. Zinc is transported mainly by albumin; hence its transport is impaired in malnutrition. Vitamin K is necessary for the production of prothrombin and other liver-derived clotting proteins that are essential in the initial phases of wound healing.

In the SarcoPhage study on mortality among malnourished older adults based on ESPEN and GLIM criteria, a total of 411 individuals were assessed (55.7% women), with a median age of 73.2 ± 6.05 years. Malnutrition according to ESPEN criteria was found in 30 (7.3%) individuals, and according to GLIM criteria in 96 (23.4%). In malnourished individuals—regardless of criteria—significantly lower BMI, lower fat-free mass index, lower appendicular fat-free mass index, lower muscle strength (all sex-adjusted P values < 0.001), more comorbidities (P = 0.008, ESPEN; P < 0.001, GLIM), poorer cognitive status (P = 0.027, ESPEN; P = 0.015, GLIM), and poorer quality of life (EuroQol: P = 0.001, ESPEN; P = 0.02, GLIM) were observed. It was shown that malnourished women had significantly worse performance in activities of daily living than well-nourished women (P = 0.015, ESPEN; P = 0.02, GLIM); among men, this difference was observed only in those who met GLIM criteria (P < 0.001).

In several studies involving populations aged 65 years and older, including some with individuals over 75 years, observational findings indicated an association between poor nutritional status and deterioration in quality of life. For example, in one analysis the odds ratio for low quality of life in malnourished patients was 2.85, while another study found that adverse effects persisted for up to 26 months.

Malnutrition impairs humoral and cellular responses, inhibits neutrophil and macrophage activity, and increases susceptibility to infections and septic complications. Vitamin C enhances resistance to infection by promoting white-blood-cell migration to the wound; its deficiency in malnutrition predisposes to infection. Zinc is an essential element required for cell replication and growth and for protein synthesis. Zinc deficiency leads to poor wound healing due to decreased immune function, disordered phagocytic activity, impaired neutrophil and lymphocyte function, copper and calcium binding interactions leading to copper and calcium deficiencies, and gastrointestinal problems such as nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea.

MMalnutrition also predicted short-term mortality after hospital discharge. In a Northern Italian cohort of 1,451 consecutively enrolled adult patients (median age 80 years) admitted to internal medicine wards at a tertiary-care hospital, nearly 16% of participants died within four months of discharge. Malnutrition was defined as BMI < 18.5 kg/m², and using this definition, malnutrition more than doubled the risk of post-discharge mortality compared with patients with normal or elevated BMI. Among patients who died in hospital, 3.2% were classified as malnourished compared with 8% of patients discharged home. The investigators explained this surprising finding as reflecting the effectiveness of nutritional interventions provided to malnourished patients, which improved survival. It is also possible that the use of BMI < 18.5 kg/m² as the measure of malnutrition explains these findings, as individuals with BMI in the normal, overweight, and obese ranges who are malnourished may be misclassified as adequately nourished or at minimal risk. Moreover, if overweight and obesity are associated with improved survival, as shown in populations with acute and chronic diseases, the estimated in-hospital mortality rate will be underestimated. In numerous cohort studies and meta-analyses using GLIM and ESPEN criteria, malnutrition is associated with a 2- to 4-fold increase in in-hospital and long-term mortality. In patients after fractures, such as femoral-neck fractures, those with malignancies, and those with heart failure, the risk of death is significantly higher.

Older patients at risk of malnutrition should be provided with higher energy intakes: 25–30 kcal/kg/day for women and 30–35 kcal/kg/day for men. It is important that meals for older patients be fixed and regular anchors in the day. Management should use high-calorie meals; in case of difficulties, high-energy liquid supplements or powdered formulas added to meals that contain essential nutrients are advisable. In a study by Gazotti et al. involving 80 patients over 75 years of age hospitalized in a Geriatric Ward in Belgium, half received additional liquid nutritional supplements. After 60 days, patients in the control group lost an average of 1.7% of body weight, whereas weight in the nutrition-support group did not change.

Intervention studies using oral nutritional supplements, dietary counseling, and multidisciplinary support often produced measurable short-term effects. In one study, protein intake increased (p = 0.009 and p = 0.02) over 16 weeks; in another, body weight increased by 1.75% (95% CI 1.12–2.30%) along with a simultaneous increase in muscle mass of 1.41% (95% CI 0.46–2.35%). However, the nutritional benefits did not consistently translate into lasting or clinically meaningful improvements in quality of life as measured by tools such as EQ-5D-5L or SF-36. By contrast, one controlled study and several observational studies showed no differences in quality of life after intervention or reported only small benefits.

It has been demonstrated that assisting hospitalized patients during mealtimes—by nurses, staff, or volunteers—Including delivering trays, positioning patients comfortably, feeding, and encouraging intake—positively affects daily energy and protein consumption.

Chewing and swallowing problems limit the ability to consume foods of normal consistency, increasing the risk of malnutrition. Modifying food texture can slow the swallowing process and thus increase safety. One intervention used to improve nutrition is percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy (PEG); however, a meta-analysis showed poor survival after placement—81% at one month, 56% at six months, and 38% at one year. [26]

The complexity of the mechanisms of malnutrition determines the appropriate therapeutic approach, such as treating the underlying cause, increasing caloric intake, using oral nutritional supplements or appetite stimulants, and, in exceptional situations, implementing parenteral or enteral nutrition. [27]

It is essential that monitoring of nutritional status encompass not only all healthcare facilities but also the home environment. Such an approach enables early prevention and, consequently, timely therapeutic actions. It is also crucial to continuously improve healthcare professionals’ qualifications and knowledge in the assessment of nutritional status and nutrition of older patients [28].

The impact of malnutrition on treatment outcomes in individuals aged 75 years and older is a complex and multifaceted clinical issue whose importance continues to grow alongside population aging. A review of current studies indicates that malnutrition is a frequent condition in this age group, has significant consequences for the course of diseases, and profoundly alters treatment trajectories — from the deterioration of postoperative parameters, through prolonged hospitalization, to increased risk of readmission and mortality [37]. At the same time, the literature reveals substantial heterogeneity in definitions, diagnostic tools, and study quality, which makes it difficult to precisely determine the magnitude of the problem and to formulate clear therapeutic recommendations [37,38]. At the epidemiological level, systematic reviews and narrative analyses document a high and variable prevalence of malnutrition among older adults, with the proportion of individuals aged ≥75 years typically higher than in younger geriatric cohorts. These differences arise from both physiological mechanisms of aging (such as decreased appetite, metabolic changes, and sarcopenia) and social or economic factors, polypharmacy, and limited access to nutritional care [38]. In recent years, attempts have been made to standardize diagnostic criteria, including the GLIM consensus, which proposes a two-step approach: initial screening combined with phenotypic and etiologic criteria for confirming malnutrition. The introduction of unified diagnostic standards is crucial for study comparability and care standardization; however, in clinical practice, a variety of tools (e.g., MNA, MNA-SF, NRS-2002, SGA) are still used, leading to inconsistent estimates of prevalence and prognostic value of nutritional status [39].

From the perspective of treatment outcomes, consistent findings from multicenter observational and retrospective studies indicate that malnutrition in older adults correlates with poorer clinical results: higher overall and perioperative mortality, increased incidence of complications (infections, delayed wound healing, metabolic disturbances), longer hospital stays, and higher readmission rates in the short and medium term after discharge [40]. Several studies applying GLIM criteria demonstrated that the severity of malnutrition is an independent predictor of adverse outcomes — the more severe the malnutrition, the worse the prognosis. In individuals aged ≥75 years, this effect may be amplified by coexisting sarcopenia and chronic inflammation, as well as by the overlap with the frailty phenotype, which complicates the interpretation of cause-and-effect relationships [39,40].

Nutritional interventions and the model of nutritional care play a crucial role in modifying these outcomes, although the quality of available evidence varies. Randomized and quasi-randomized trials, as well as hospital-based quality programs, have shown that early screening and the implementation of nutritional strategies (including oral nutritional supplements — ONS, targeted dietary support, patient and caregiver education, and post-discharge nutritional follow-up) can reduce the number of complications, shorten hospital stays, and lower 30- and 90-day mortality and readmission rates [40,41]. A classic example is a study showing significant benefits of intensive nutritional intervention among hospitalized geriatric patients, with reduced mortality and improvement in selected clinical parameters. Nevertheless, many studies have methodological limitations (small sample sizes, lack of blinding, short follow-up periods), which weaken the strength of recommendations regarding specific treatment protocols for the 75+ population [41]. An important research challenge lies in distinguishing the effect of malnutrition from the impact of coexisting multimorbidity and frailty. In many analyses, malnutrition co-occurs with a higher number of chronic diseases, poorer cognitive function, and lower physical activity — all of which are independent risk factors for poor treatment outcomes. This creates the risk of overinterpreting correlation as causation [35]. From a methodological perspective, future studies require statistical models that account for a broad range of confounding factors, as well as interventional designs capable of assessing the impact of specific nutritional strategies independently of coexisting clinical conditions [36].

In clinical practice, however, the implications are clear: systematic nutritional screening in individuals aged ≥75 years, prompt confirmation of diagnosis using standardized criteria (e.g., GLIM after positive screening), and the implementation of a comprehensive, multidisciplinary nutritional care plan should become the standard of care, particularly for hospitalized patients and those scheduled for surgical procedures. The effectiveness of such interventions is most likely to increase when combining multiple components: supplementation (ONS), nutrition therapy tailored to energy and protein requirements, physical rehabilitation aimed at maintaining muscle mass, and continuity of care after discharge [37].

In conclusion, although there is a strong body of evidence linking malnutrition to poorer treatment outcomes in older adults — as well as clear indications that targeted interventions can improve these results — there remains a lack of large, well-designed interventional studies focused exclusively on the 75+ population. Long-term studies are also needed to evaluate the effects of nutritional interventions on function, quality of life, independence, and cost-effectiveness within healthcare systems. In clinical practice, routine nutritional screening, the use of standardized diagnostic criteria, early implementation of nutritional care plans, and systematic monitoring of outcomes are recommended — as these measures have genuine potential to improve treatment results in the oldest patients and to reduce the burden on healthcare systems [38].

Many observational studies and systematic reviews consistently demonstrate an association between malnutrition and worse treatment outcomes in older adults — higher mortality, more frequent complications, longer hospital stays, and increased rates of readmission [39]. However, the magnitude of the effect and its statistical significance vary between studies, which stems from several key methodological differences: the definitions of malnutrition used, the nature of the studied population (hospitalized vs. outpatient vs. community-dwelling), the age and level of multimorbidity of participants, and the duration and accuracy of follow-up. For example, analyses using the GLIM criteria report a wide range of malnutrition prevalence and confirm the prognostic importance of malnutrition severity, whereas studies employing MNA or SGA produce different prevalence estimates and results that are not always directly comparable. Standardization of diagnoses (e.g., GLIM) improves comparability, but validation studies still show discrepancies between tools in detecting and grading malnutrition[40].

Comparison of interventional studies reveals similar discrepancies. Large, well-designed trials (for example, programs that include early screening and comprehensive nutritional intervention, as well as studies of specialized ONS containing HMB) have shown beneficial effects on some hard end points — improvement in nutritional indices, muscle strength, and, in selected trials, reduction of mortality and complications. Nevertheless, not all trials confirmed these effects, and positive results more often come from studies that combined nutritional interventions with rehabilitation programs and post-discharge care, suggesting that the effect is greatest with a multidisciplinary approach. Classic trials such as NOURISH and related analyses signal benefits, but their generalizability to an exclusively ≥75 years population is limited because they frequently enrolled broad cohorts of older adults and the oldest subgroups were relatively small [40,41].

The strengths of the evidence base include primarily the consistency of the observational signal and the emergence of unified diagnostic criteria (GLIM). Numerous studies and reviews show a repeatable association between poor nutritional status and adverse clinical outcomes, which increases the credibility of a real clinical relationship. A global consensus facilitates the conduct of more comparable studies and allows validation of tools across different populations [29,30]. The evidence base is also strengthened by interventional data indicating practical benefits: randomized and quasi-randomized trials and quality-improvement programs suggest that early detection and comprehensive intervention (ONS, dietetic support, rehabilitation, continuity of care) can improve short-term outcomes [30].

Weaknesses of the evidence base include heterogeneity of definitions and instruments, a predominance of observational studies, limitations of interventional trials, and poor representation of the oldest and most multimorbid patients. Different screening and diagnostic instruments (MNA, NRS-2002, SGA, GLIM) yield varying estimates of prevalence and prognostic power; many studies do not apply a unified scheme, which complicates comparisons across studies [31,32]. A large portion of the evidence linking malnutrition to outcomes comes from observational research, which is susceptible to confounding (multimorbidity, frailty, cognitive function, socio-economic status). Many analyses do not fully control for these variables. RCTs of nutritional interventions often have limited statistical power (small sample sizes), short follow-up, lack of blinding, or heterogeneous protocols (different ONS formulations, varying intervention durations). This weakens the strength of evidence, particularly regarding long-term outcomes and the 75+ population. The most rigorous trials frequently exclude individuals with severe disability or advanced disease, which limits the applicability of results to real-world patients aged ≥75 [33,34].

The greatest interpretive challenge is distinguishing to what extent malnutrition is a cause of adverse outcomes versus a coexisting marker of more severe disease or frailty. Because many studies are observational, there is a real risk of residual confounding — for example, malnourished patients may simultaneously have poorer cognitive function, a history of more hospitalizations, or weaker social support — all factors that independently increase the risk of poor outcomes regardless of nutritional status. To mitigate this problem, both broader cohort analyses with rigorous control of confounders and RCTs specifically targeting the ≥75 population with robust randomization, adequate power, and longer follow-up are needed [35,36].

The clinical implications of the identified patterns are as follows: given the predictable negative consequences of malnutrition, clinicians should perform routine nutritional screening in patients aged ≥75 (in hospital, primary care, and long-term care). After a positive screen, diagnosis should be confirmed using unified criteria (e.g., GLIM) or a validated tool appropriate for the setting. Standardization will facilitate quality monitoring and comparison of program effects [39,40].

Comprehensive, multidisciplinary intervention programs: Best outcomes are observed where nutritional actions are part of a broader program involving a dietitian, rehabilitation, medication review (de-prescribing), social support, and post-discharge care. In practice, this means creating nutritional care pathways in hospitals and geriatric care systems with clear protocols for ONS, meal planning, anti-sarcopenia exercise, and post-discharge monitoring [41].

Tailoring the intervention to patient and goal: The choice of intervention (e.g., type of ONS, duration, integration with a home exercise program) should be individualized: in patients with sarcopenia the emphasis should be on protein and resistance training; in those with swallowing disorders on texture modification and possible speech-therapy support [42].

Monitoring outcomes and continuity of care: The effectiveness of nutritional therapy should be assessed across multiple dimensions: nutritional parameters (body weight, muscle indices), function (handgrip strength, mobility), clinical indicators (complications, length of stay, readmissions) and quality of life. Continuity of care after discharge (access to ONS, follow-up with dietitians/rehabilitation) is crucial to maintain gains [43].

Based on the critical appraisal of the literature [42,43,44] , I propose the following steps: prioritize RCTs targeted to the ≥75 population (with adequate power and long follow-up); widespread use of GLIM or other standardized criteria with reporting of age subgroups; studies comparing specific protocols (ONS type, duration, rehabilitation components) with measurement of clinical and economic outcomes; and in practice — immediate implementation of routine screening, rapid diagnostics, and comprehensive nutritional care pathways with outcome monitoring [44].

Evidence clearly indicates that malnutrition in people aged 75+ is an important predictor of poorer treatment outcomes and that targeted, multidimensional nutritional interventions have the potential to improve clinical results. However, heterogeneity of diagnostic tools, predominance of observational studies, and methodological limitations of many interventional trials weaken the strength of recommendations for a single universal protocol. In light of this, the optimal clinical strategy combines routine screening and standardized diagnostics (GLIM), rapid implementation of personalized nutritional interventions as part of a multidisciplinary program, and rigorous outcome monitoring — while concurrently generating more high-quality RCTs focused specifically on the ≥75 population [45].

This narrative review has several limitations. First, although the literature search covered major databases (PubMed, Scopus, Web of Science, and Clinical Nutrition) and included studies up to early 2025, the analysis was limited to articles published in English, which may have led to language bias. Second, the heterogeneity of study designs, diagnostic tools, and outcome measures among the included papers made direct comparison difficult and precluded quantitative synthesis. Third, only 41 studies met the inclusion criteria, and many of them involved mixed-age cohorts with limited representation of individuals aged 75 years and older. Finally, as a narrative rather than systematic review, the findings should be interpreted as a comprehensive but descriptive synthesis rather than a meta-analytic summary of evidence.

Malnutrition in adults aged 75 years and older significantly worsens disease course, prolongs hospitalization, increases complications and mortality, and impairs quality of life. Nutritional status is a stronger prognostic factor than chronological age. Early detection and correction of malnutrition using validated tools such as MNA-SF, NRS-2002, SGA, and standardized ESPEN or GLIM criteria should be integral to geriatric care. Individualized strategies ensuring adequate protein intake, balanced diet, and physical activity help maintain functional independence.

Despite progress in diagnostic standardization, evidence for the ≥75 population remains limited, underscoring the need for large, prospective studies to assess long-term benefits of nutritional interventions and their impact on survival and quality of life.

Klaudia Kontek – conceptualization, methodology, writing- original draft, editing.

Olaf Helbig – literature search, data extraction, writing- review & editing.

Bartosz Bobrowski – data interpretation, clinical insights, review of manuscript.

Honorata Derlatka – methodology, supervision, manuscript editing.

Jan Drugacz – literature search, drafting sections, reference verification.

Anna Kuhtiak – manuscript preparation, formatting, data validation.

Julia Marcinkowska – data extraction, figures and tables preparation.

Martyna Radelczuk – writing – review & editing, critical revision.

Łukasz Skowron – supervision, clinical expertise, finalapproval of the manuscript.

All authors have read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Artificial intelligence tools, such as ChatGPT and other OpenAI systems, were used to support language refinement, structural improvement, and the development of certain text sections (including results and conclusions). All AI-generated contributions were thoroughly reviewed and verified by the authors.