- Home

- About the Journal

- Peer Review

- Editorial Board

- For Authors

- Reviewer Recognition

- Archive

- Contact

- Impressum

- EWG e.V.

Cite as: Archiv EuroMedica. 2025. 15; 6. DOI 10.35630/2025/15/Iss.6.619

Background: Periodontally Accelerated Osteogenic Orthodontics (PAOO) is an advanced technique that combines conventional orthodontic treatment with selective corticotomy and alveolar bone augmentation to significantly shorten treatment time. By inducing the Regional Acceleratory Phenomenon (RAP), PAOO enhances bone remodeling and allows tooth movement up to three times faster than traditional methods.

Aim: The aim of this article is to analyze the data in the available literature regarding aspects of periodontally accelerated orthodontic therapy such as reduction in treatment time, variation in surgical techniques, and patient satisfaction.

Methods: An internet-based search was performed for the articles published until 2025 identified through targeted searches of PubMed/MEDLINE, Embase, Cochrane Library using keywords periodontal accelerated orthodontic tooth movement, corticotomy, PAOO, periodontally accelerated osteogenic orthodontics, tooth movement, and treatment duration.

Results: On analysis, it was observed that earlier studies primarily focused on animal and preliminary clinical models to evaluate biological mechanisms such as the Regional Acceleratory Phenomenon (RAP). More recent clinical trials and case series demonstrated that PAOO can reduce treatment duration by approximately 30–70% compared with conventional orthodontic therapy. Most studies reported enhanced alveolar bone thickness and improved post-treatment stability, with minimal adverse effects when proper case selection and surgical protocols were followed. Patient satisfaction levels were generally high due to shorter treatment time, improved facial aesthetics, and reduced risk of root resorption.

Conclusions: Most of the studies included in the review concluded that there was a significant reduction in orthodontic treatment duration using periodontal accelerated techniques compared to conventional orthodontic treatment.

Keywords: periodontally accelerated osteogenic orthodontics; corticotomy; regional acceleratory phenomenon; orthodontic treatment acceleration; alveolar bone augmentation; adult orthodontic treatment

An increasing number of adult patients seek orthodontic treatment, motivated by growing aesthetic demands and heightened oral health awareness. Conventional orthodontic therapy typically lasts between 12 and 24 months, depending on the complexity of the case, treatment objectives, and patient-specific factors. Prolonged treatment is associated with risks such as root resorption, caries, gingival inflammation, enamel demineralization, and periodontal disease, often due to compromised oral hygiene over extended treatment periods.

Tayer [1] found that 33% of adult patients were discouraged from having orthodontic treatment due to the length of treatment and the discomfort and inconvenience involved with having orthodontic appliances. A major concern for adult orthodontic patients is the prolonged length of treatment. Adults tend to desire a shorter treatment time and demand more aesthetic appliances [2]. Reducing the total duration of orthodontic treatment remains a major objective in contemporary clinical research. Over the years, numerous surgical and less invasive, non-surgical strategies have been proposed to accelerate tooth movement.

Non-surgical methods primarily focus on optimizing orthodontic biomechanics through the use of advanced bracket systems and archwires. Additionally, biological approaches include the local delivery of cellular mediators and the use of adjunctive therapies such as electromagnetic and magnetic field stimulation, low-level laser therapy, and mechanical vibrations to enhance the rate of tooth movement. Surgical techniques, on the other hand, encompass procedures like fiberotomy, osteotomy, corticotomy, and piezocision, as well as the application of skeletal anchorage devices. These interventions are intended to reduce overall treatment time and lower the risk of orthodontically induced root resorption and periodontal problems [25]. It is important to remember that the prevalence of periodontal issues tends to rise with age, making the interplay between orthodontics and periodontics crucial in managing such patients. However, as reported by Gehlot M. et al. [26], orthodontic treatment does not appear to have a detrimental impact on periodontal health once periodontal stabilization has been achieved in periodontally compromised individuals. In addition, in individuals with a healthy periodontium, PAOO is an emerging alternative that leverages accelerated bone remodeling to facilitate faster tooth movement while simultaneously enhancing periodontal support [40]. Adult patients and their expectation for shorter treatment durations, caused that innovative strategies have been developed to accelerate orthodontic tooth movement. Among these, surgical adjunctive techniques remain the most effective and predictable. Periodontally Accelerated Osteogenic Orthodontics (PAOO) combines traditional orthodontics with selective alveolar corticotomy and bone grafting, enabling tooth movement two to three times faster than conventional methods. This multidisciplinary approach addresses several limitations of standard orthodontics and has revolutionized adult orthodontic care. This procedure also reduces the need for extraction and also increases bone support for teeth and soft tissues

Although several reviews describe the concept of Periodontally Accelerated Osteogenic Orthodontics (PAOO), the present article provides one of the most up-to-date syntheses, including clinical and biological evidence published in 2024–2025. This review integrates current knowledge on surgical protocols, biological mechanisms such as the Regional Acceleratory Phenomenon (RAP), modern grafting strategies (e.g., sticky bone), and the expanding role of PAOO in aligner-based therapy. This makes the work relevant for clinicians seeking evidence-based guidance applicable to contemporary orthodontic practice.

AIM

The aim of this review is to critically evaluate current scientific evidence on Periodontally Accelerated Osteogenic Orthodontics (PAOO) with emphasis on its biological foundation, clinical effectiveness, and surgical variations.

An extensive electronic literature search was conducted to identify studies related to Periodontally Accelerated Osteogenic Orthodontics (PAOO) and other corticotomy-assisted orthodontic procedures. The databases searched included PubMed/MEDLINE, Embase, and the Cochrane Library, covering publications up to 2025. The following keywords and their combinations were used: periodontally accelerated osteogenic orthodontics, PAOO, Wilckodontics, corticotomy-assisted orthodontics, orthodontic tooth movement, treatment duration, and Regional Acceleratory Phenomenon (RAP). Boolean operators “AND” and “OR” were applied to refine the search strategy.

Included: Clinical trials, randomized controlled trials (RCTs), prospective and retrospective studies, and case series related to PAOO; Studies evaluating treatment duration, bone and periodontal changes, patient satisfaction, or surgical techniques; Articles published in English.

Excluded: Case reports without sufficient methodological details; Review articles without primary data; Animal studies not directly related to PAOO clinical applications.

The reference lists of relevant articles were manually screened to identify additional studies. Data were extracted regarding study design, sample size, intervention protocol, outcome measures, and key findings. Qualitative synthesis was performed due to the heterogeneity of study methodologies and reported outcomes.

Surgical approaches to facilitate orthodontic tooth movement date back to the 1800s. For over a century, basic surgical techniques have been employed to enhance or accelerate the movement of teeth [4]. The concept of surgically assisted orthodontic tooth movement dates back to the 19th century. In 1893, Cunningham [3] introduced the “luxation” technique during the International Dental Congress in Chicago, using interproximal osteotomies to reposition palatally inclined maxillary teeth. Stabilization was achieved with wires or metal splints for 35 days, and treatment duration was significantly reduced to approximately one-third of the conventional timeline. L.C. Bryan described facilitated tooth movement through corticotomy in 1893, later published by S.H. Guiliford [5]. Subsequent efforts combined alveolar osteotomy with corticotomy to enhance orthodontic efficiency. In 1950s Dr Gabriel Ilizarov promoted Distraction Osteogenesis (DO). According to him stressing a bone increases metabolic activity and cellular generation, also known in orthopedic science as ‘bone remodeling’. A pivotal milestone was Heinrich Kole’s 1959 publication [6], introducing the “bone block movement theory.” Kole proposed that the cortical bone layer represented the primary resistance to tooth movement. His approach involved raising a mucoperiosteal flap, creating interproximal cuts through the cortical plate into cancellous bone, and connecting them apically around the teeth to form mobilizable bone blocks.

Bell and Levy (1972) [7] conducted the first experimental animal study of alveolar corticotomy in 49 monkeys. Duker (1975) [8] carried out a study on beagle dogs and demonstrated that rapid tooth movement could be achieved by orthodontic appliance by weakening the bone with corticotomy. In 1983 Harold Frost and Jee [9] first described The Regional Acceleratory Phenomenon (RAP) which is the biological foundation of accelerated tooth movement in PAOO. They discovered direct correlation between the degree of injured bone and the intensity of its healing response. However, it was not until 2001 when an innovative technique designed to preserve periodontal health and accelerate orthodontic tooth movement was developed by Dr. William Wilcko (orthodontist) and Dr. Thomas Wilcko (periodontist)[10]. This method, called periodontally accelerated osteogenic orthodontics (PAOO) and widely known as Wilckodontics, combines orthodontic treatment with periodontal procedures to achieve faster and more efficient results [17, 15]. Nowadays, PAOO can also be combined with clear aligner systems such as Invisalign, providing patients with a more aesthetic and comfortable treatment experience. The integration of advanced orthodontic technologies not only accelerates tooth movement but also offers a discreet and convenient option for individuals seeking to enhance their smile with minimal interference in daily life [14].

The table below presents the chronological development of Periodontally Accelerated Osteogenic Orthodontics

Table 1. Historical development of Periodontally Accelerated Osteogenic Orthodontics (PAOO)

| Year | Researcher(s) |

| 1893 | Cunningham |

| 1893 | L.C Bryan |

| 1950 | Gabriel Ilizarov |

| 1959 | Heinrich Kole |

| 1972 | Bell & Levy |

| 1975 | Duker et al |

| 1983 | Frost & Lee |

| 2001 | Wilcko Brothers |

Orthodontics (PAOO) and related biological concepts. It highlights the key researchers and their contributions that shaped the evolution of corticotomy-assisted orthodontic techniques, from early experimental approaches to the modern PAOO protocol introduced by the Wilcko brothers in 2001.[3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,14,15,17]

PAOO can be performed under local or general anesthesia. A full-thickness mucoperiosteal flap is carefully elevated to expose the alveolar bone at the intended corticotomy sites. The flap should extend beyond the surgical area mesially and distally to avoid vertical releasing incisions. For aesthetic reasons, preserving the interdental papilla between the maxillary central incisors is crucial; access in this region may be achieved through a tunneling approach from the distal aspect.

It is important to state the differences between the four types of surgical damage in alveolar bone: Osteotomy (complete cut through cortical and medullar bone), corticotomy (partial cut of cortical plate without penetrating medullar bone), ostectomy (removal of an amount of cortical and medullar bone) and corticotectomy (removal of an amount of cortex without medullar bone) [23]. Decortication involves perforating the cortical bone adjacent to teeth targeted for movement. This step aims to trigger the Regional Acceleratory Phenomenon (RAP) without creating mobile bone segments. Using a low-speed round bur or a piezoelectric knife (piezocision), decortication is performed without penetrating the cancellous bone, minimizing the risk of damaging vital structures such as the maxillary sinus or mandibular canal.

According to Kotula et al. [33], superior outcomes are achieved when the procedure is combined with tissue augmentation. Moreover, „sticky bone”, a combination of heterologous bone material and autologous blood barrier membranes, successfully preserved the bone height and thickness 1 year after PAOO surgery [38]. Therefore, following decortication, bone graft materials such as bovine xenograft, autogenous bone, or demineralized freeze-dried bone allograft (DFDBA) are placed over the surgical sites. The typical graft volume ranges from 0.25 to 0.5 mL per tooth, depending on the alveolar bone thickness and augmentation requirements. The use of leukocyte- and platelet-rich fibrin (L-PRF) in combination with graft materials has been shown to reduce postoperative inflammation, pain, and infection risk while preserving tooth movement dynamics and stability. [12]

The flap is repositioned and sutured with non-resorbable sutures under minimal tension. Periodontal dressing is not necessary, and sutures are typically removed after 1–2 weeks. Sufficient time is allowed for the epithelial attachment to re-establish.

Orthodontic appliances are usually placed one week before surgery. However, in cases involving complex mucogingival procedures, delaying appliance placement until after surgery can facilitate flap handling and suturing. Orthodontic forces should be applied immediately or within two weeks postoperatively to take advantage of the RAP window, which typically lasts about four months. During this period, rapid progression to larger archwires is recommended. Combining PAOO with Aligners offers patients a more aesthetic and comfortable treatment option. Aligners are discreet and removable, allowing patients to maintain confidence throughout treatment and making oral hygiene easier, thereby reducing the risk of caries and periodontal disease [14].

The Regional Acceleratory Phenomenon (RAP), first described by Frost in 1983 is a localized tissue response to injury that enhances healing capacity in both hard and soft tissues. It occurs following fractures, osteotomies, or bone grafting and involves the recruitment and activation of cells essential for tissue remodeling. Wilcko et al. demonstrated via CT imaging that rapid tooth movement in PAOO is not due to bone block displacement but rather a transient demineralization-remineralization cycle within the alveolar housing. This pattern aligns with the wound healing response characteristic of RAP. In alveolar bone, RAP is associated with increased activation of basic multicellular units (BMUs), resulting in expanded remodeling spaces. Alveolar surgery may also stimulate mesenchymal stem cell (MSC) production in marrow spaces, synergizing with periodontal ligament and bone cells to further accelerate tooth movement [27]. Tooth movement rates peak between days 22 and 25 post-surgery, with corticotomy-treated sites showing approximately double the movement rate compared to controls. RAP can accelerate hard tissue healing by 10–50 times and typically lasts around four months in human bone [24]. Incorporating bone grafting into PAOO further enhances bone mass and improves long-term stability. According to Alsino HI et al The PAOO procedure was effective in accelerating orthodontic movement and tended to increase the thickness of the alveolar bone [21]. As reported by Darwiche F et al., the orthodontic–microsurgical technique enables new orthodontic movement while reducing the risks of bone resorption and ligament ankylosis, shortening treatment duration by up to 60% in the mandible and 70% in the maxilla [42]. Gil et al.,state that corticotomy-facilitated orthodontic treatments required a reduced treatment length of 8.85 months compared to conventional orthodontic therapy, which lasted an average of 16.4 months [30,13].

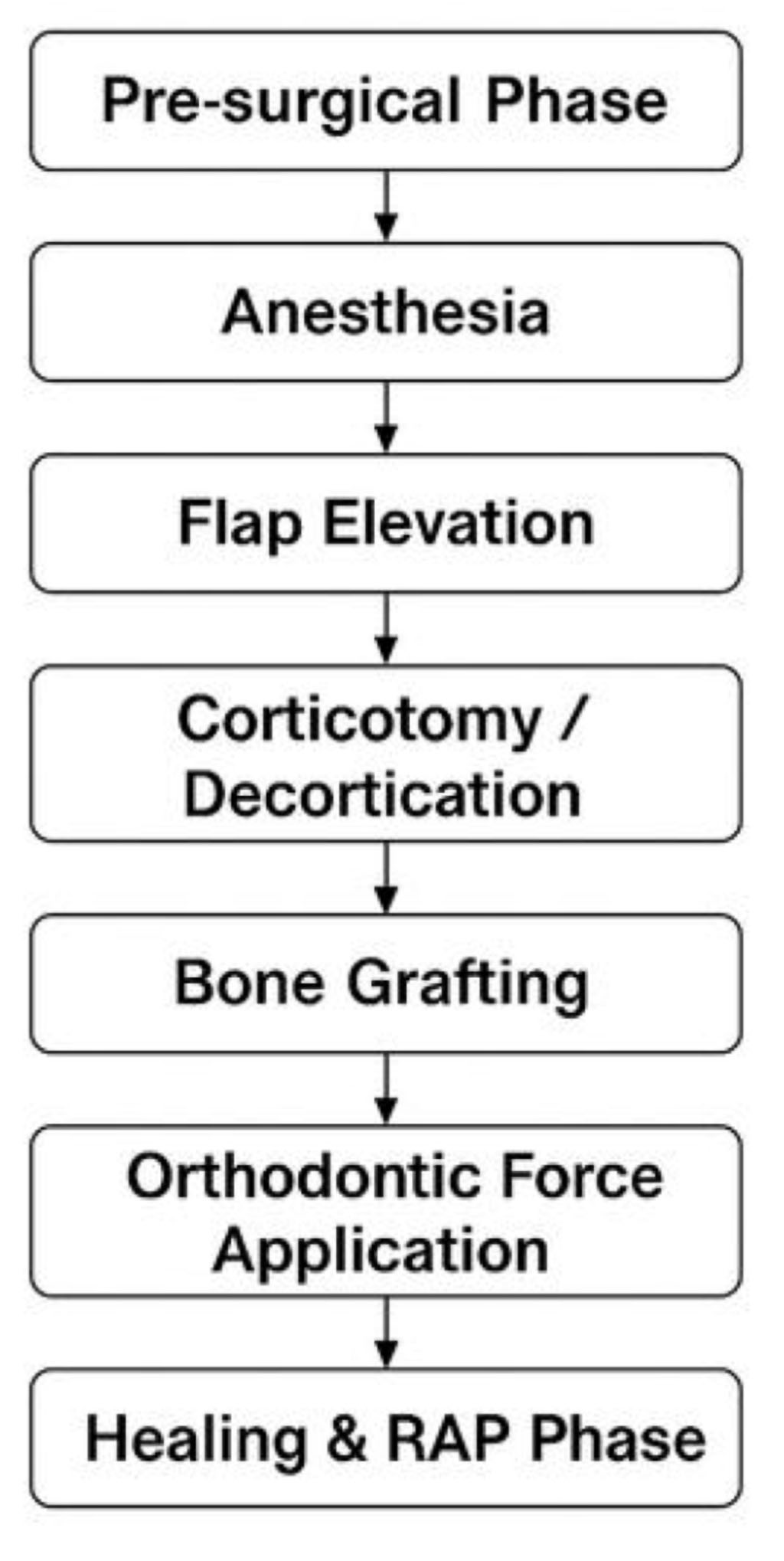

Figure 1 illustrates the sequential stages of the Periodontally Accelerated Osteogenic Orthodontics.

Figure 1. Flow chart of PAOO procedure

Orthodontics (PAOO) procedure. The process begins with the pre-surgical phase and anesthesia, followed by flap elevation, corticotomy or decortication, and bone grafting. Orthodontic force is subsequently applied, initiating the healing and Regional Acceleratory Phenomenon (RAP) phase that facilitates accelerated tooth movement. [12, 13, 14, 16, 21, 24, 27, 30, 31, 33, 38, 42]

The following table summarizes the main clinical indications and contraindications for the application of Periodontally Accelerated Osteogenic Orthodontics (PAOO). The indications include cases where accelerated tooth movement and alveolar bone augmentation provide therapeutic advantages, while the contraindications highlight systemic and local conditions that may compromise treatment outcomes or bone healing.[11,16,18,28,29,32,36,37,39,44].

Table 2. Indications and contraindications of PAOO

| Indications [29,11,18,32,36,39,44] | Contraindications [16,28,29] |

| Resolution of moderate to severe crowding | Thin mandibular cortical plate |

| Class II malocclusions requiring expansion or extraction | Bimaxillary protrusion with a gummy smile |

| Mild Class III malocclusions | Severe skeletal Class III malocclusion |

| Canine retraction after premolar extraction | Untreated endodontic lesions |

| Facilitation of impacted tooth eruption | Bone metabolism disorders, such as osteoporosis or systemic disease |

| Assistance in slow orthodontic expansion | Long-term NSAID or corticosteroid therapy (impairing bone metabolism and prostaglandin synthesis) |

| Molar intrusion and open bite correction | Active periodontal disease or multiple gingival recessions |

| Crossbite and dental discrepancy management | Severe posterior crossbite |

| Anterior open bite and midline deviation correction | Ankylosed teeth |

| Anchorage manipulation | |

| Optimization of treatment of patients with cleft lip and palate |

The decision regarding maxillary or mandibular application depends on clinical needs. For example, maxillary expansion, which is typically slower, may benefit more from PAOO than mild mandibular crowding.

Like every medical procedure, Periodontally Accelerated Osteogenic Orthodontics has its advantages and limitations. Although this technique significantly shortens treatment time and enhances post-treatment stability, it is not without potential risks and contraindications. The main benefits and limiting factors of this method are presented below.

The following table summarizes the main advantages and limitations of the PAOO (Periodontally Accelerated Osteogenic Orthodontics) procedure.[22,24,34,35,37,41,43]

Table 3. PAOO: Advantages and Limitations

| Advantages | Limitations |

| Increased alveolar bone and periodontal volume, lowered recession, reduced dehiscences and fenestrations | Requires a surgical procedure with associated risks such as pain, swelling, and infection |

| Accelerated treatment time (up to three- to fourfold faster) | Not suitable for medically compromised patients or those on long-term NSAID therapy |

| Enhanced post-treatment stability and reduced relapse risk | Chances of damage to the roots of adjacent teeth |

| Expanded treatment possibilities, potentially avoiding extractions or orthognathic surgery | Increased cost of the procedure has to be borne by the patient |

| Improved facial profile and smile aesthetics | Not indicated in all orthodontic cases |

| Accelerated eruption of impacted teeth | Chances of appearance of interproximal black triangles |

| Reduced risk of root resorption |

Periodontally Accelerated Osteogenic Orthodontics (PAOO) represents a significant advancement in orthodontic therapy, integrating selective alveolar corticotomy, bone grafting, and orthodontic mechanics to enhance tooth movement through the Regional Acceleratory Phenomenon (RAP). Consistent with the first objective of this review, the available literature confirms the biological foundation of PAOO, in which RAP induces transient demineralization and accelerated bone turnover, allowing tooth movement up to three times faster than in conventional treatment [12,13,21,24,27]. With regard to the second objective, studies demonstrate substantial variability in surgical protocols, including depth and extent of corticotomy, instrument selection, and the use of grafting materials. The incorporation of DFDBA, xenografts, or L-PRF enhances periodontal outcomes, increases alveolar bone thickness, and reduces the risk of root resorption when compared with corticotomy alone [45]. Evaluation of clinical effectiveness (Objective 3) consistently shows that PAOO reduces overall treatment duration by approximately 30–70%, increases alveolar bone volume, decreases the incidence of fenestrations and dehiscences, and improves post-treatment stability [12,13,21,24,27,30,43]. When combined with clear aligner systems, PAOO additionally offers superior comfort and aesthetics compared with traditional fixed appliances [14]. Finally, in accordance with Objective 4, limitations of PAOO must be acknowledged. The technique requires a minor surgical intervention and is contraindicated in patients with systemic bone metabolism disorders, active periodontal disease, or those undergoing long-term NSAID or corticosteroid therapy, which may impair bone remodeling [16,28,29]. Furthermore, variability in surgical protocols and the limited number of large-scale randomized clinical trials remain major constraints in fully standardizing the procedure.

In summary, the current evidence indicates that PAOO is a biologically sound and clinically effective approach for adult orthodontic patients, offering significant reductions in treatment duration while maintaining periodontal health and long-term stability.

The evolution of accelerated tooth movement techniques, initiated as early as 1893, has continued to advance, with PAOO gaining particular momentum over the past decade as refinements have improved both clinical predictability and patient acceptance [19]. In line with the aim and research objectives of this review, PAOO combines orthodontic mechanics with selective alveolar corticotomy and bone augmentation to reduce treatment duration, enhance periodontal support, and improve post-treatment stability. The literature consistently demonstrates that PAOO accelerates orthodontic tooth movement, increases alveolar bone volume, reduces complications, and expands treatment possibilities for adult patients. Successful outcomes depend on careful patient selection, accurate diagnosis, and interdisciplinary planning. PAOO remains a valuable tool in contemporary orthodontics, bridging periodontal and orthodontic disciplines and advancing treatment possibilities beyond traditional mechanics. Despite its strong clinical potential, further randomized controlled trials are needed to standardize surgical protocols and evaluate long-term stability. Overall, Wilckodontics represents a highly successful treatment modality and offers a “win–win” solution for both the patient and the clinician [20].

Conceptualization: Damian Truchel, Adam Janota, Zuzanna Muszkiet

Methodology: Aleksandra Rysak, Damian Truchel

Investigation: Anna Krzywda, Aleksandra Rysak, Zuzanna Muszkiet, Adam Janota,

Data curation: Mikołaj Bluszcz, Zuzanna Dynowska, Anna Krzywda

Writing- original draft: Damian Truchel, Zuzanna Muszkiet, Mikołaj Bluszcz, Aleksandra Rysak, Dominik Poszwa, Zuzanna Dynowska, Anna Krzywda

Writing- review and editing: Zuzanna Muszkiet, Adam Janota, Damian Truchel, Aleksandra Rysak, Zuzanna Dynowska

Validation: Damian Truchel, Mikołaj Bluszcz, Adam Janota, Dominik Poszwa

Visualization: Damian Truchel, Aleksandra Rysak, Zuzanna Dynowska

Supervision: Zuzanna Muszkiet, Damian Truchel, Anna Krzywda

Project administration: Zuzanna Muszkiet, Michał Bar, Damian Truchel, Dominik Poszwa

The authors acknowledge the use of artificial intelligence tools, Grok (created by xAI) and ChatGPT (created by OpenAI), for assistance in drafting initial versions of certain sections and polishing the language of the manuscript. These tools were used to enhance clarity and organization of the text. All content was thoroughly reviewed, edited, and validated by the authors to ensure scientific accuracy, integrity, and alignment with the study’s objectives.

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.