- Home

- About the Journal

- Peer Review

- Editorial Board

- For Authors

- Reviewer Recognition

- Archive

- Contact

- Impressum

- EWG e.V.

Cite as: Archiv EuroMedica. 2025. 15; 6. DOI 10.35630/2025/15/Iss.6.612

Myxofibrosarcoma is a rare, aggressive soft tissue sarcoma, usually occurring at an older age. The tumors most often involve the limbs. MFS frequently mimics benign conditions, leading to delayed diagnosis. This case describes an 80 year old woman who was initially diagnosed and treated for presumed prepatellar bursitis. The failure of surgical treatment and the rapid enlargement, erythema and necrosis, followed by histopathological examinations, CT and MRI imaging finally led to definitive diagnosis of high-grade (FNCLCC 3) MFS. The patient underwent neoadjuvant radiotherapy, followed by wide surgical excision with gastrocnemius muscle flap and skin graft reconstruction. This case highlights the diagnostic difficulty of MFS due to its ability to masquerade as common illnesses, despite its malignant nature, and emphasizes the importance of a multidisciplinary approach in specialized centers for the treatment of soft tissue tumors.

Keywords: Myxofibrosarcoma, Soft tissue sarcoma, Prepatellar region, High-grade sarcoma (FNCLCC G3), Neoadjuvant radiotherapy, Wide local excision, Gastrocnemius flap reconstruction

Myxofibrosarcoma (MFS) is an aggressive and rare malignant neoplasm, which represents type of soft tissue sarcoma. It is diagnosed particularly in elderly patients, usually between 60 and 80 years old. Clinically, the first manifestation is a painless, slow growing nodule. The most common sites for this sarcoma are the extremities, followed by the trunk, pelvis, the head and neck region, and the genital area [1]. Although the diagnosis is established via histological examination, a major challenge is defining the boundaries of the tumor. The standard approach involves the use of high quality T1- and T2-weight with pre- and post-gadolinum imaging [2]. The diagnostic and therapeutic complexity poses a challenge that should be managed by a multidisciplinary medical team. The primary treatment for localized tumor is surgical resection with (neo)adjuvant radiotherapy and/or chemotherapy. In the case of metastatic disease, chemotherapy is the standard, although the prognosis is unfavorable, with limited chance of achieving complete remission [3].

An 80-year-old woman presented to the outpatient orthopedic clinic with a several-month history of a palpable nodule over the left knee. Her medical history included breast cancer treated surgically, ischemic stroke and transient ischemic attack, chronic kidney disease, bronchial asthma, and degenerative spine disease.

Physical examination revealed a firm, tender 2-cm lesion over the prepatellar region with preserved knee range of motion and no changes in skin appearance. Prepatellar bursitis was diagnosed, and aspiration of bursal fluid was performed. Symptom recurred and the procedure was repeated.

After the second aspiration, the lesion enlarged rapidly, this time also swelling and erythema were present. The patient was scheduled for surgical evacuation of a prepatellar hematoma. Resection of the prepatellar bursa, evacuation of hematoma, and removal of fibrotic tissue were performed, and tissue samples were obtained for histopathological analysis.

Within one month post-surgery, the lesion expanded dramatically to ~7 cm, became markedly erythematous, cyanosed, and showed areas of necrosis. This raised a suspicion of a malignant tumor which led to extended diagnostic. CT imaging identified a soft-tissue mass with dense fluid components (73 × 40 × 70 mm), without patellar destruction or intra-articular effusion (Fig 1, 2).

Figure 1: CT scan of the knee joint with Myxofibrosarcoma (MFS). Sagittal plane.

Figure 2: CT scan of the knee joint with Myxofibrosarcoma (MFS). Axial plane.

First histopathological result suggested an atypical non-epithelial lesion. Further evaluation in a reference laboratory revealed a malignant, partially pleomorphic tumor with high proliferative activity (Ki-67: 90%) and focal necrosis. Immunohistochemistry, where Vimentin+, CD10+, CD68+, focal CD34/CD31+, β-catenin+, Cyclin D1+ where present, excluded malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumor and synovial sarcoma, leading to a preliminary diagnosis of undifferentiated/unclassified sarcoma.

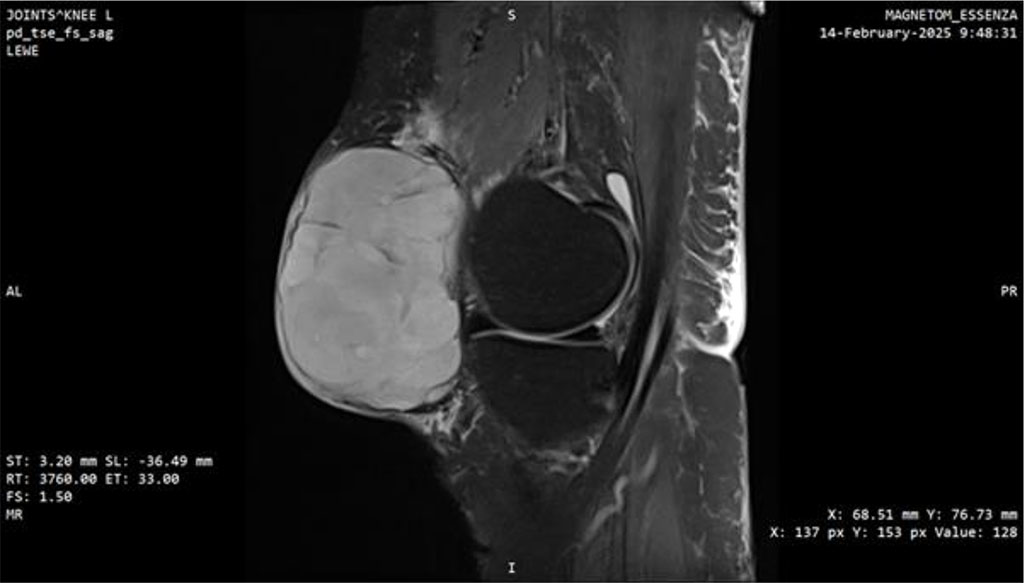

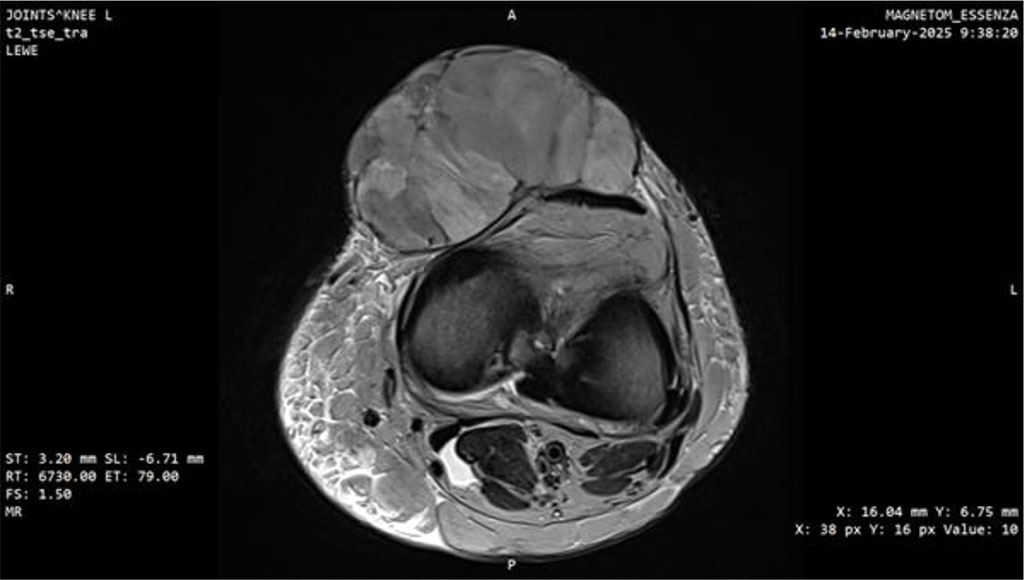

At this point, the patient was transferred to a center of the highest reference, specializing in sarcomas. MRI performed there demonstrated a well-defined, heterogeneously enhancing solid mass measuring 77 × 45 × 78 mm with surrounding fat stranding. A repeat biopsy was performed, and the third histopathological result confirmed myxofibrosarcoma, FNCLCC grade 3 (Fig. 3, 4).

Figure 3: MRI scan of the knee joint with Myxofibrosarcoma (MFS). Sagittal plane.

Figure 4: MRI scan of the knee joint with Myxofibrosarcoma (MFS). Axial plane.

The patient underwent neoadjuvant radiotherapy to the left knee region (6 Gy per fraction to a total of 30 Gy) without complications. Subsequent wide local excision including fascia was performed, followed by placement of a VAC dressing. One week later, reconstruction was completed, using the medial head of the gastrocnemius muscle and a split-thickness skin graft harvested from the left thigh. The postoperative course was uneventful.

Serial imaging of the chest and spine throughout treatment showed no evidence of metastatic disease. The surgical wounds healed adequately, and the patient regained full functional status. She remains under long-term surveillance at the sarcoma reference center.

Myxofibrosarcoma (MFS) typically presents as painless, slowly growing masses. In 30–60% of cases, they are located in the extremities [1], as in our patient’s case. Due to the heterogeneous clinical presentation, misdiagnoses are common during the diagnostic process of MFS [4]. The symptoms which are often scarce, can delay the implementation of extensive diagnostic procedures. This was also observed in our case, where the tumor was initially mistaken for a benign condition. The absence of alarming signs, such as rapid tumor growth, systemic symptoms, or pain, led to originally conservative approach.

The suspicion of a malignant etiology appeared only after the accelerated growth of the mass and the presence of signs of inflammation, which became evident after several weeks of ineffective treatment. In high-grade sarcomas, including the case presented here, rapid tumor growth after surgical manipulation is not uncommon. The disruption of the tumor architecture may unmask its infiltrative potential and promote growth through changes in the tumor microenvironment [5]. This emphasizes the importance of re-evaluating the initial diagnosis when treatment fails.

Histopathological diagnosis can also be challenging, as MFS can exhibit pleomorphism, a myxoid stroma, and necrosis, features that can overlap with other types of sarcomas or benign reactive lesions[6]. Moreover, MFS doesn’t possess a specific immunophenotype [7]. In our patient’s case, it was only the third histopathological examination, performed at reference center, that led to the establishment of a definitive diagnosis. Therefore, in cases suspicious for MFS, it would be advised to do comprehensive histopathological workup and implement close interdisciplinary collaboration. These are essential to increase the likelihood of correct diagnosis and optimal patient management.

Ultrasonography should be considered the first-line imaging test [8], whereas magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is primarily used for assessing tumor grade, extent, and infiltration during treatment planning. A characteristic MRI feature of MFS is the “tail sign,” reflecting its infiltrative growth pattern [9].

Soft tissue sarcomas, including MFS, are graded according to the FNCLCC (Fédération Nationale des Centres de Lutte Contre le Cancer), which evaluates: 1) tumor differentiation, including cellular atypia and morphological features; 2) mitotic index, defined as the number of mitoses per 10 high-power fields (HPF); and 3) the presence of necrosis.

The main differential diagnoses for MFS include malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumors, myxoma, low-grade fibromyxoid sarcoma, pleomorphic leiomyosarcoma, pleomorphic rhabdomyosarcoma, spindle cell lipoma, pleomorphic or dedifferentiated liposarcoma, melanoma, undifferentiated carcinoma, undifferentiated sarcoma, and nodular fasciitis [10].

Evidence supports treatment in specialized centres, where patients receive coordinated and comprehensive care [11]. The basis of treatment is wide radical surgical excision. Some tumors that are going deep into the tissue, may require reconstructive procedures, as was performed in our patient. Surgical margins should range from 1 to 2 cm to minimize local recurrence [12]. Adjuvant radiotherapy is recommended for grade 2 and 3 tumors to reduce the risk of recurrence and improve prognosis. Some studies report no significant difference in local recurrence rates between irradiated and non-irradiated patients [13], whereas others suggest radiotherapy can prevent local recurrence during the first five years after treatment [14]. In our case, radiotherapy was used to reduce tumor volume before the surgery. The role of chemotherapy in MFS remains unproven, although combined chemoradiotherapy may bring benefits to patients, where complete resection is not possible [15]. Combination immunotherapy may enhance tumor response, particularly in advanced cases with distant metastases [16].

Distant metastases occur in approximately 30% of patients, most commonly affecting the lungs, then bones and soft tissues [6]. In our patient, regular chest CT scans performed after malignant tumor was suspected showed no evidence of metastatic disease. Appropriate surveillance after treatment of the highest priority for monitoring disease spread. Overall prognosis is moderately favorable, with 5-year survival rates typically going from 65% to 70% [17]; however, outcomes may worsen depending on tumor size, stage, patient age, and concurrent disease. MFS is associated with a high rate of local recurrence, appearing in approximately 39% of patients [17], and notably, late recurrences may occur even up to 10 years after remission [18]. Therefore, long-term follow-up is essential, with prompt intervention if signs of recurrence arise.

MFS is often characterized by slow growth and painlessness, which is why it can often be misdiagnosed as benign. Histopathological diagnosis is also difficult due to the lack of specific markers for this tumor. Furthermore, MFS can present a diverse histopathological appearance, which can mimic benign lesions, further complicating diagnosis.

Ultrasound is the basis of MFS diagnostic imaging. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is also crucial in treatment planning, as it allows for the assessment of tumor grade and depth of invasion. MRI may also reveal a characteristic "tail sign," illustrating an infiltrative growth pattern. Treatment primarily relies on wide surgical excision of the tumor, with a margin of 1-2 cm. Due to deep invasion, reconstructive surgery is often necessary to restore function to the operated limb. For grade 2 and 3 tumors, some sources recommend adjuvant radiotherapy to reduce the likelihood of tumor recurrence.

One of the fundamental factors determining patient survival is a rapid and accurate diagnosis. Therefore, it is crucial to be particularly vigilant when making a diagnosis and to respond immediately if conservative treatment fails, and especially if the patient's condition worsens. In such cases, the patient should be immediately referred to specialized centers experienced in the diagnosis and managing soft tissue tumors. Due to the high recurrence rate, which can occur up to a decade after treatment, long-term follow-up in an oncology clinic at a referral center is crucial.

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for the publication of this clinical case and any accompanying images.

Conceptualization: Maria Spychalska

Methodology: Maria Spychalska, Jan Spychalski

Formal analysis: Maria Spychalska, Jan Spychalski

Investigation: Maria Spychalska, Jan Spychalski

Writing-rough preparation: Maria Spychalska, Jan Spychalski

Writing-review and editing: Maria Spychalska, Jan Spychalski

Supervision: Maria Spychalska

All authors have read and agreed with the published version of the manuscript.

The authors declare that no artificial intelligence tools were used in the generation, writing, editing, or revision of this manuscript. All content was created solely by the authors.

The article did not receive any funding.

Authors declare no conflicts of interest.