- Home

- About the Journal

- Peer Review

- Editorial Board

- For Authors

- Reviewer Recognition

- Archive

- Contact

- Impressum

- EWG e.V.

Cite as: Archiv EuroMedica. 2025. 15; 3. DOI 10.35630/2025/15/3.323

Introduction: Chronic pain is a major global public health issue, affecting an estimated 20% of adults worldwide. Prevalence is particularly high among the elderly and those in long-term care. In Poland, up to 30% of adults are affected, with even higher rates observed among institutionalized populations. Osteoarthritis is the most frequent cause, accounting for over one-third of cases. Despite ongoing medical advances, effective management of chronic pain remains a major clinical challenge due to its multifactorial etiology and high interindividual variability.

Aim: This narrative review aims to provide a comprehensive and integrative summary of current knowledge on chronic pain, including its pathophysiological mechanisms, classification, and modern management strategies. Particular attention is given to pharmacological and non-pharmacological approaches, with an emphasis on the role of individualized, interdisciplinary care in improving patient outcomes.

Methods: A narrative literature review was conducted using PubMed and Google Scholar. The search prioritized large cohort studies, systematic reviews, meta-analyses, and recent mechanistic investigations. Studies addressing both pharmacological and non-pharmacological methods of chronic pain management were selected based on scientific relevance and evidence quality.

Results: Pharmacological treatment includes nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), opioids, antidepressants, and anticonvulsants, although their use is often limited by adverse effects and reduced long-term efficacy. Non-pharmacological interventions such as physiotherapy, psychotherapy, relaxation techniques, neuromodulation, and lifestyle modification play a crucial role in improving patient quality of life and functional status. An individualized treatment plan based on a biopsychosocial model is considered the most effective approach.

Conclusions: Chronic pain management requires personalized, interdisciplinary strategies aimed not solely at symptom relief but at enhancing daily functioning and well-being. Improved access to comprehensive pain services and increased awareness among healthcare professionals and patients are essential for optimizing outcomes.

Keywords: Chronic Pain, pain classification, pain mechanisms, neuropathic pain, pain treatment, pharmacological pain management, non-pharmacological pain management and multidisciplinary pain therapy.

According to the International Association for the Study of Pain (IASP), chronic pain is defined as pain that persists or recurs for more than three months and extends beyond the expected period of tissue healing [1,2]. It may be continuous or intermittent and classified as nociceptive, neuropathic, or mixed in origin. Chronic pain is frequently associated with impaired quality of life, emotional distress, sleep disorders, and significant physical and social limitations.

Globally, chronic pain affects approximately 20% of the adult population—over 1.5 billion people—with prevalence ranging from 13% to over 50% in some low- and middle-income countries [8–10].

In Poland, an estimated 27–30% of adults experience chronic pain, representing nearly 8.5 million individuals [3–5]. Prevalence increases with age, reaching approximately 63% among people over 85 years, and as high as 83–93% among residents of long-term care institutions. Women constitute around 60% of those affected. The most common cause of chronic pain in Poland is osteoarthritis, accounting for about 34% of diagnosed cases [6,7].

Due to its multifactorial nature and chronic course, pain significantly impacts patients across psychological, physical, social, and economic domains, posing a considerable burden on healthcare systems and societies.

This narrative review aims to provide a comprehensive and integrative summary of current knowledge on chronic pain, including its pathophysiological mechanisms, classification, and modern management strategies. Particular attention is given to pharmacological and non-pharmacological approaches, with an emphasis on the role of individualized, interdisciplinary care in improving patient outcomes.

This article is a narrative review based on literature published between January 2013 and April 2024. Sources were identified through searches in the PubMed and Google Scholar databases using combinations of keywords such as “chronic pain,” “pain classification,” “pain mechanisms,” “neuropathic pain,” “pain treatment,” “pharmacological pain management,” “non-pharmacological pain management,” and “multidisciplinary pain therapy.”

Priority was given to clinical guidelines, large cohort studies, systematic reviews, meta-analyses, and high-impact narrative reviews. Studies involving adult populations were primarily selected, while pediatric studies were included only where relevant. Articles not available in English or Polish, conference abstracts, and non-peer-reviewed content were excluded.

The review includes 46 peer-reviewed sources, with a focus on publications from the last 5 years. References were screened for scientific relevance, topicality, and quality of evidence.

The sensation of pain serves as a warning signal of injury and triggers appropriate protective responses. Acute pain is usually physiological in nature and directly related to tissue damage, whereas chronic pain is a pathological phenomenon, often unrelated to any current injury. The process by which acute pain becomes chronic is referred to as chronification [12][13].

At the root of pain perception lies the complex process of nociception, which includes transduction, transmission, modulation, and final perception occurring in brain structures. The proper functioning of these mechanisms is influenced by genetic factors, which explains individual differences in pain sensitivity threshold, pain tolerance, and predisposition to develop chronic pain [14].

A tissue-damaging stimulus activates proteolytic enzymes that act on kininogens (tissue proteins), leading to the release of kinins (polypeptides) that depolarize naked nerve endings. Damaged tissues also release histamine, which has similar effects to kinins. The pain impulse is then conducted via A fibers (myelinated) and Cdr fibers (unmyelinated).

Neurons of the Cdr fiber group, located in spinal ganglia, release neuropeptides such as substance P, calcitonin gene-related peptide (CGRP), vasoactive intestinal peptide (VIP), somatostatin, and galanin. These neuropeptides are released not only at synapses, where they act on the second-order sensory neuron in the dorsal horn, but also at the terminals of sensory fibers within the innervated tissues.

The pathway of pain impulse conduction overlaps with that of temperature receptors (cold and heat). Neuronal fibers in the dorsal horn cross to the opposite side of the spinal cord and ascend to the brain via the lateral spinothalamic tract.

The third-order sensory neuron is located in the thalamus, within the ventroposterolateral and ventroposteromedial nuclei. The fourth-order neuron resides in the sensory fields of the cerebral cortex, in the postcentral gyrus, and in the secondary sensory representation areas in the frontal-parietal operculum and the insula cortex.

In addition to this specific pathway, pain impulses are simultaneously transmitted through multineuronal, non-specific pathways [15].

Pain impulse inhibition occurs in the dorsal horn of the spinal cord and in thalamic nuclei. Additionally, opioid receptors located in the cell membranes of neurons in brain regions bind with endogenous opioid peptides, acting as synaptic modulators [16].

Chronic pain can be classified into several main types: nociceptive, neuropathic, psychogenic, and complex mixed pain. Only 20–25% of patients experience a single type of pain; the rest experience two or more types [17]. The frequency and nature of chronic pain vary significantly depending on the patient’s age (Table 1).

Table 1. Nature of Chronic Pain Depending on Patient Age

| Age Group | Most Common Pain Types | Clinical Characteristics |

| Children (0–17 years) |

Functional Psychosomatic |

Strong influence of psychological factors, frequent injuries |

| Young Adults (18–40 years) |

Nociceptive Onset of Neuropathic |

Overuse, post-traumatic, and musculoskeletal pain |

| Middle-Aged

Adults (41–60 years) |

Nociceptive Neuropathic Mixed |

Complex pathophysiology, higher incidence of radicular pain |

| Seniors (60+ years) |

Nociceptive Neuropathic Mixed |

Multifactorial pain syndromes |

Source: [18][19][20][21].

Nociceptive pain arises as a result of stimulation of nociceptors that respond to noxious stimuli, such as inflammatory mediators. Prolonged exposure to such stimuli can lead to peripheral sensitization, characterized by a lowered threshold for nociceptor activation and increased activity of sodium channels. This results in increased neuronal excitation and enhanced transmission of pain signals to the dorsal horns of the spinal cord.

At the spinal level, this leads to so-called central sensitization, or increased neuronal reactivity to stimuli. This process involves, among others, activation of NMDA receptors and changes in gene expression. Central sensitization contributes to exaggerated responses to painful stimuli (hyperalgesia) and pain in response to normally non-painful stimuli (allodynia).

Clinical studies suggest that pain hypersensitivity can cause structural changes in the brain over time. However, these changes are reversible once pain is effectively managed [22][23].

Neuropathic pain results from damage to or disease of the somatosensory nervous system. Peripheral nerve injury triggers a cascade of molecular changes. In the dorsal root ganglion, protein particles are produced, gene expression is altered, and changes occur in potassium and calcium ion channels. There is also upregulation of tetrodotoxin-sensitive sodium channels and formation of new adrenergic receptors. These alterations lead to spontaneous neuronal discharges, contributing to spontaneous pain. [13][22]

Additionally, pathological connections ephaptic transmission may form between nerve fibers, underlying phenomena such as allodynia. An inflammatory process, involving mediators such as bradykinin, serotonin, and cytokines, can also induce neuropathic pain even without direct nerve injury. [23]

Within the central mechanisms, central sensitization plays a crucial role. This includes both functional and structural changes from synaptic and transcriptional modifications, to glial cell proliferation and nerve fiber sprouting. During this process, activated microglia in the dorsal horn of the spinal cord release mediators like brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF), which reduces the inhibitory effect of neurotransmitters GABA and glycine. This leads to disinhibition of synapses and activation of polysynaptic pathways, amplifying pain signal transmission from the damaged nerve.

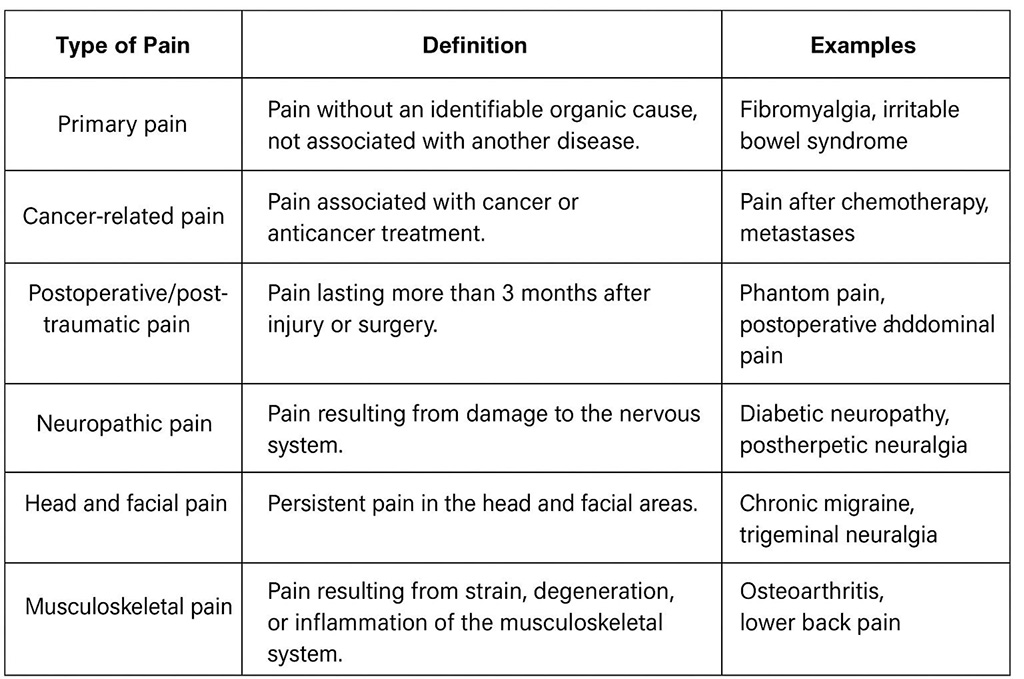

As a result, complex networks of mutual excitations and positive feedback loops are formed. Once these surpass physiological regulatory limits, they may become self-perpetuating, leading to persistent chronic pain [24][25]. Table 2 outlines types of chronic pain and provides definitions and examples.

Table 2. Types of Chronic Pain: Definitions and Examples

Source: [9][10] [3] [6] [7].

Chronic pain significantly increases the risk of depression, anxiety disorders, hopelessness, and social isolation. It disrupts sleep by making it harder to fall asleep and causing frequent awakenings, leading to chronic fatigue. Constant discomfort also lowers mood and reduces stress tolerance [1][2][10]

It leads to avoidance of physical activity and, in some cases, even immobilization. It impairs daily functioning and the ability to perform basic daily tasks, and may hinder or prevent professional work [3][4].

Individuals experiencing chronic pain may withdraw from social life and interpersonal relationships. It may strain family dynamics, leading to tension and conflict. In addition, decreased concentration and work performance can result in job loss [10][5].

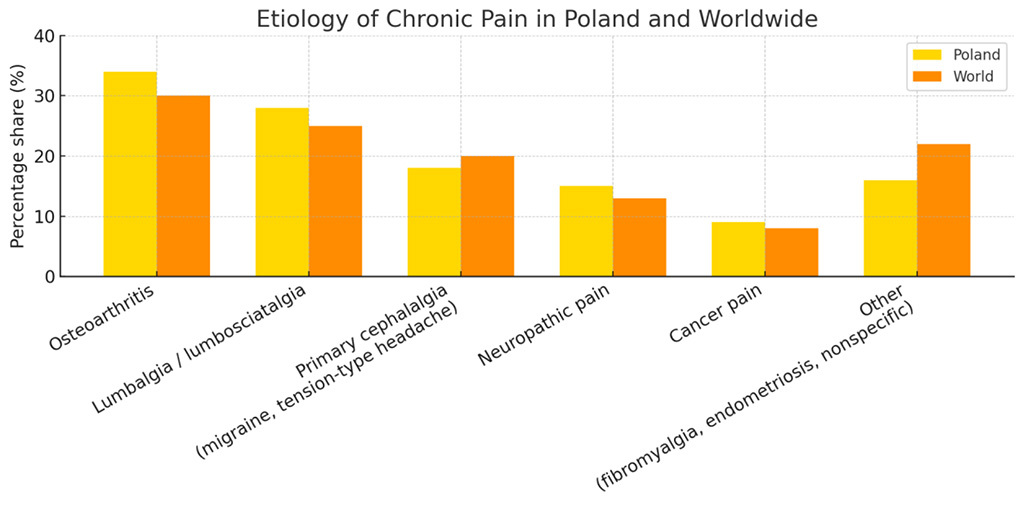

Chronic pain generates significant expenses related to medical visits, medications, rehabilitation, and alternative therapies [3][11]. The distribution of underlying causes plays a key role in shaping both the clinical approach and the associated economic burden of chronic pain syndromes, as illustrated in Chart 1.

Chart 1. Etiology of Chronic Pain in Poland and Worldwide

Source: [3][4] [11] [6][7].

Pharmacological treatment of chronic pain is based on selecting medications according to the type and intensity of the pain. It should be individualized, taking into account drug efficacy, tailored to the clinical condition of the patient, and the benefits of the treatment should outweigh the potential side effects [26].

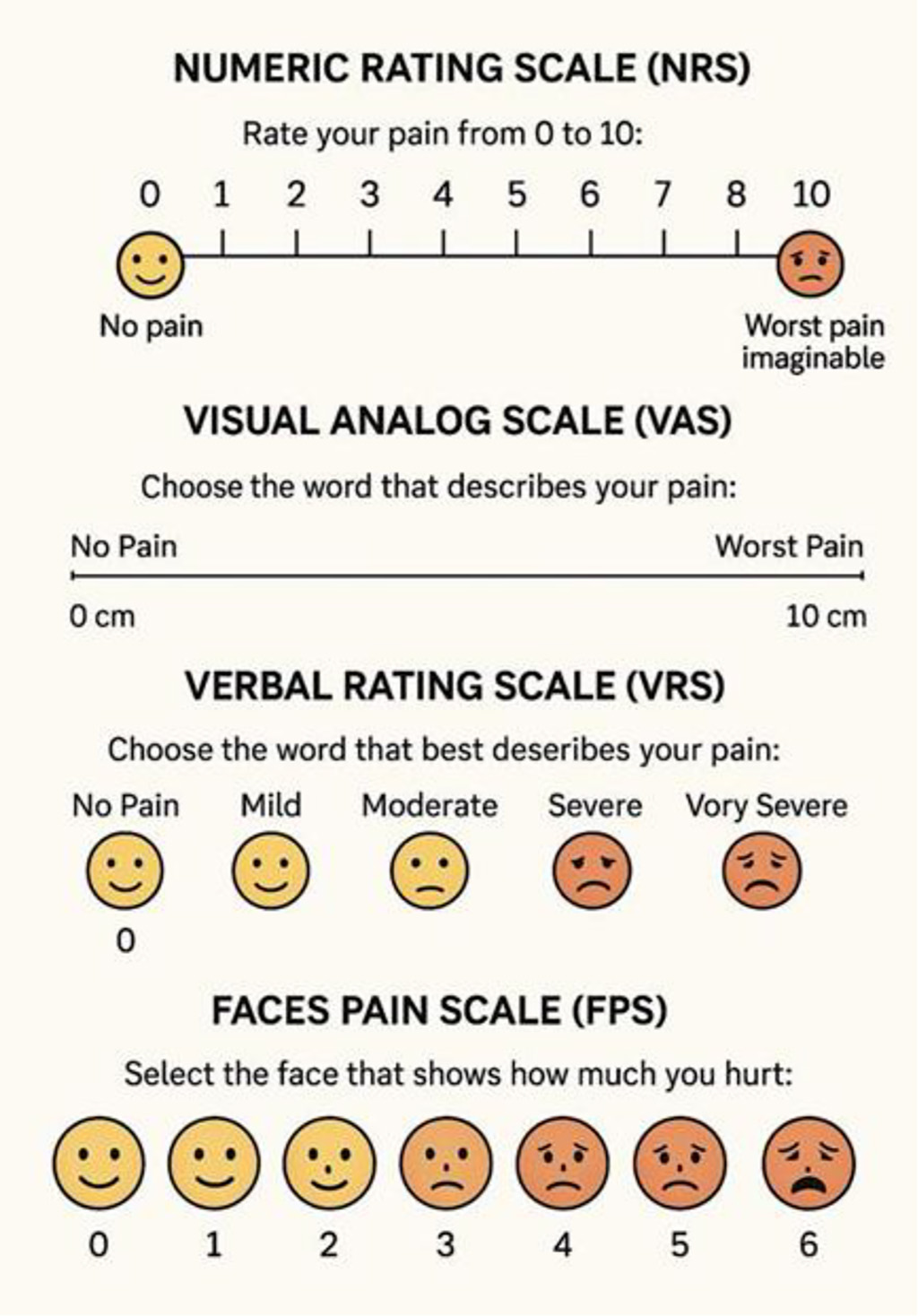

To determine the appropriate therapeutic approach, pain intensity assessment scales are commonly used. Recommended scales for assessing pain intensity include (Chart 2) [26]:

Chart 2. Pain rating scales

Based on the result obtained using one of the above-mentioned scales, pain can be classified according to its intensity. The following categories are distinguished:

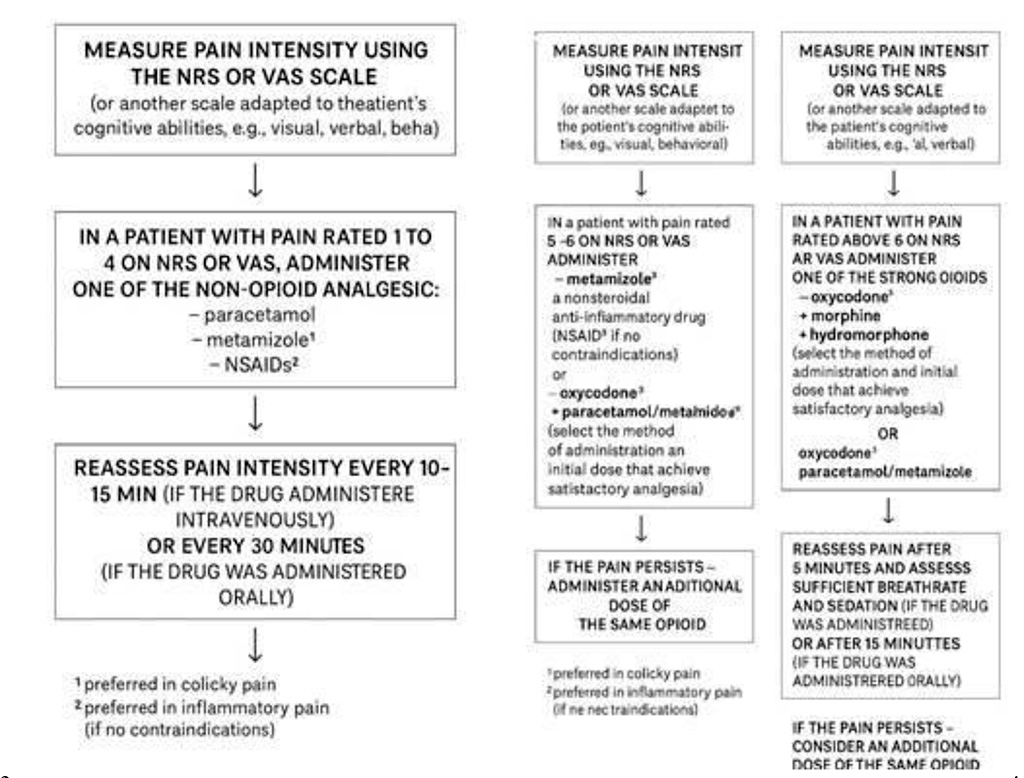

Chart 2 presents the most frequently reported forms of chronic pain in clinical populations. Understanding the predominant forms of chronic pain provides essential context for evaluating the therapeutic strategies most commonly employed in clinical practice, as shown in Chart 3.

Chart 3.Treatment of mild, moderate and severe pain based on NRS scale or VAS scale

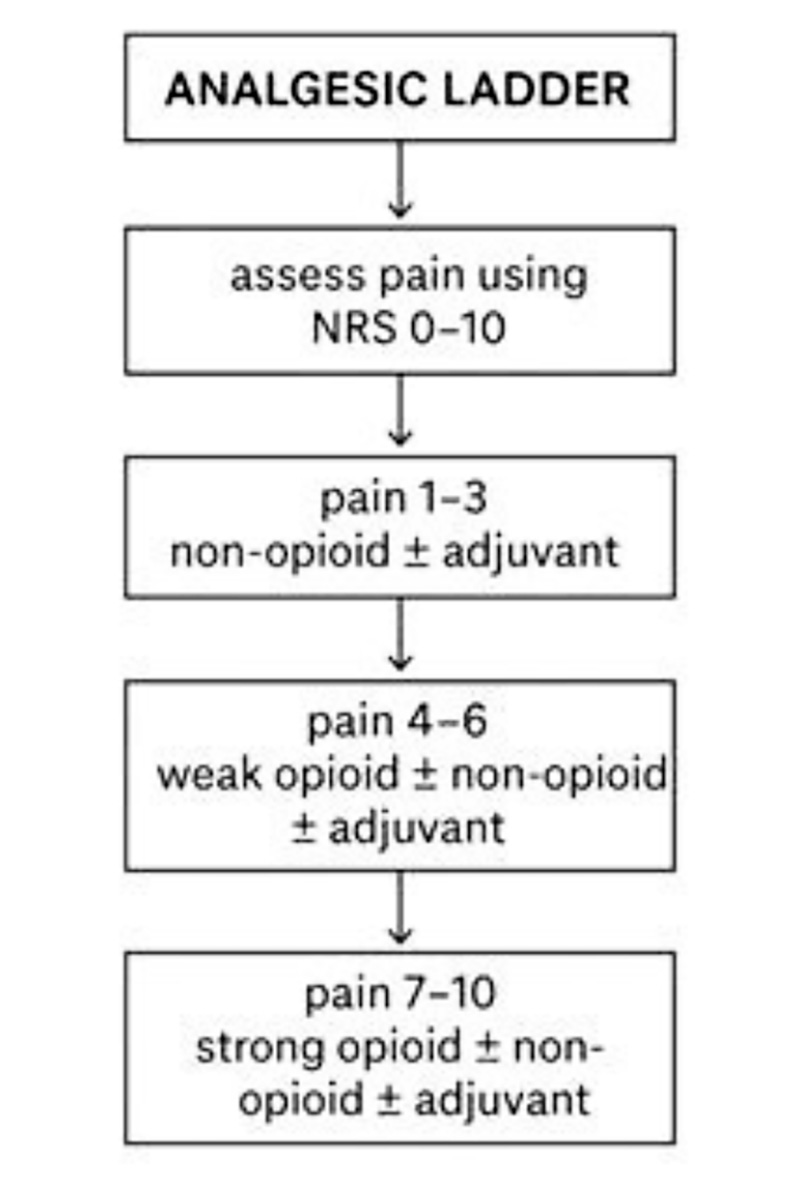

After determining the intensity of the pain, it is possible to implement pharmacological treatment with a lower risk of adverse effects [28]. Chart 4 illustrates the WHO analgesic ladder for pharmacological treatment of chronic pain, a stepwise model guiding the use of analgesics according to pain intensity and therapeutic response.

Chart 4. Pharmacotherapy based on the WHO analgesic ladder.

Source: [29].

The principles of pain management are based on several key assumptions aimed not only at relieving pain but also ensuring the patient’s safety and comfort. First and foremost, the strength of the analgesic should correspond to the intensity of the pain — it should neither be underestimated nor overtreated. It is equally important to match the drug’s mechanism of action to the underlying cause of pain: first-line medications such as paracetamol are ineffective for neuropathic pain, while non-anti-inflammatory drugs will not be effective in treating inflammatory pain [30][31].

The choice of drug must also consider individual patient characteristics — age, organ function, comorbidities, and concomitant medications. In chronic pain therapy, adjuvant drugs (also known as co-analgesics) are often introduced. Although they are not classic painkillers, they significantly enhance the effectiveness of treatment, especially in cases of neuropathic or cancer-related pain [30] [31] [29].

To increase analgesic efficacy, combination therapy is frequently used — combining drugs with different mechanisms of action but similar pharmacokinetics (i.e., drugs that act over the same time frame). For example, opioids can be combined with agents that act on serotonin, norepinephrine, or the endocannabinoid system. Such strategies utilize synergistic and pleiotropic effects that enhance pain relief through different pathways [30] [31].

The preferred routes of administration for pain medications are oral or transdermal, as they are the most convenient and least invasive for patients [32].

Among the drugs used to treat chronic pain are:

Paracetamol – an analgesic and antipyretic with minimal adverse effects on the gastrointestinal tract and kidneys. It is primarily used to treat mild to moderate somatic pain. As it is mainly metabolized in the liver, caution is necessary in patients with hepatic impairment. Maximum daily dose: 4 g [32].

Metamizole – an analgesic, antipyretic, and spasmolytic. Used in the treatment of pain caused by renal colic, postoperative pain, and menstrual pain. Contraindications include allergies, hypotension, hypovolemia, and pregnancy. Maximum daily dose: 5 g [32].

NSAIDs (Non-Steroidal Anti-Inflammatory Drugs) – possess anti-inflammatory, analgesic, and antipyretic properties. Commonly used for musculoskeletal pain. Doses vary by substance:

Tramadol – a weak opioid with a dual mechanism of action: it stimulates opioid receptors and inhibits the reuptake of norepinephrine. Used to treat acute, cancer, or spinal pain. Caution is advised in patients with a history of addiction. Side effects may include headache, drowsiness, nausea, vomiting, and constipation. Maximum dose: 400 mg/day [32].

Codeine – indicated for mild to moderate pain, especially when non-opioid analgesics are ineffective. It is also used to relieve post-traumatic, postoperative pain and suppress coughing. Adverse effects include respiratory depression, constipation, and drowsiness. Maximum daily dose: 240 mg [32].

Morphine – a strong opioid used primarily for dull, persistent pain [32]. Side effects include nausea, vomiting, itching, dizziness, urinary retention, and risk of dependence. Used for cancer-related and postoperative pain.

Fentanyl – a very potent opioid, used in severe chronic cancer pain or in patients intolerant to morphine [32]. Considered a second-line drug. Side effects include drowsiness, nausea, vomiting, and constipation. It should not be used with SSRIs due to the risk of serotonin syndrome.

Buprenorphine – used for cancer and neuropathic pain, usually administered via transdermal patches [32]. Adverse effects include constipation, drowsiness, nausea, vomiting, and skin reactions. Available patch strengths include 5, 10, 20, and up to 40 μg/hour.

Oxycodone – similar to morphine but considered more potent. Indicated in cancer, postoperative, receptor-mediated, and neuropathic pain [32]. Frequently combined with naloxone to reduce opioid-induced constipation.

Proper use of analgesic drugs requires not only knowledge of their strength but also their mechanisms of action, safety profiles, and potential for combination therapy. Ultimately, the goal is not only to eliminate pain but also to improve the patient’s quality of life [35][33].

One of the most recent breakthroughs in pain management involves medications targeting the CGRP (calcitonin gene-related peptide) pathway and its receptors. These therapies provide significant relief for individuals suffering from migraines and represent a major advancement in the treatment of this type of pain [36].

In addressing other mechanisms responsible for pain, an important development will be the introduction of suzetrigine into routine clinical practice. This medication, expected to be approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in 2025, is designed for the treatment of postoperative pain and works by selectively blocking sodium channels of the NaV1.8 type [37].

In the near future, new formulations of opioid medications are expected to enter clinical use, including a combination of tramadol and magnesium, which will soon become available. At the same time, research is ongoing into combining oxycodone with magnesium, where the magnesium additive aims to enhance the analgesic effect while reducing the incidence of side effects [38].

Additionally, innovative oxycodone formulations are being developed to prevent both accidental and intentional overdoses. The new tablet design is intended to limit the release of high doses of the active substance in cases where multiple tablets are ingested at once [39].

Soon, new extended-release versions of pregabalin are also expected to become available. Pregabalin is a well-established first-line treatment for patients with neuropathic and nociplastic pain. These new formulations will allow for once or twice-daily dosing, thereby improving treatment adherence and patient comfort [40].

According to the biopsychosocial model, pain is the result of an interaction between biological, psychological, and social factors. Treatment of chronic pain should focus not only on eliminating physical symptoms but also on providing psychological support and addressing the patient’s social functioning.

In the absence of visible tissue damage, psychological factors-such as emotions and cognitive processes-have the greatest influence on the perceived intensity of pain. Due to the complex nature of pain, effective treatment requires collaboration among specialists from various medical and therapeutic disciplines-including physicians, psychologists, nurses, physiotherapists, and occupational therapists-forming what is known as an integrated, multidisciplinary approach to pain management.

The goal of this approach is not necessarily the elimination of pain, but rather the improvement of quality of life despite ongoing pain. Research shows that this method produces better outcomes than pharmacotherapy alone [41].

The multimodal approach to pain management should include not only medication but also self-care (such as weight loss, a healthy lifestyle, and sleep hygiene), psychotherapy, and physical exercise. Less invasive and safer methods should be introduced before resorting to invasive procedures.

The most common form of self-treatment is physical exercise, which is more effective in improving daily function than in directly reducing pain. An exercise program should be individually tailored to the patient’s specific condition [42].

Invasive pain treatment methods such as nerve blocks, denervation, IDDS, and nerve stimulation are not included in the classical analgesic ladder and are reserved for patients who do not respond to pharmacological treatment. Their effectiveness varies and is often limited to specific cases [41].

The Intrathecal Drug Delivery System (IDDS) involves the direct administration of medication into the intrathecal space (around the spinal cord). Commonly used medications include opioids, bupivacaine, clonidine, and ziconotide. IDDS therapy is indicated for conditions such as spasticity, cancer pain, complex regional pain syndrome, and failed back surgery syndrome. This method allows for lower opioid doses and fewer side effects, but it is associated with certain risks and limited evidence of long-term effectiveness [41] [42] [43].

Spinal Cord Stimulation (SCS) delivers electrical impulses to the dorsal horn of the spinal cord via electrodes implanted in the dorsal epidural space. This technique, based on the gate control theory, generates an electric field that inhibits activity in the spinothalamic tract by stimulating axons in the dorsal horn and dorsal column.

SCS is particularly recommended for chronic, treatment-resistant neuropathic pain persisting for more than six months. SCS devices can be remotely programmed, and modern models are patient-rechargeable. Additionally, by improving tissue perfusion and reducing the need for limb amputation, SCS can be beneficial in ischemic pain, such as in peripheral artery disease or refractory angina.Spinal Cord Stimulation is a well-established method for treating chronic neuropathic pain conditions – studies have shown approximately a 50–70% reduction in pain in about half of the patients. [44][45]

Deep Brain Stimulation (DBS) involves the implantation of electrodes into brain regions involved in pain processing, such as the periaqueductal gray matter and the thalamus. This method is highly invasive and carries significant risk, and is therefore reserved for carefully selected patients with intractable chronic pain. DBS is approved for use in Europe.

In contrast, non-invasive techniques such as repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation (rTMS) and transcranial direct current stimulation (tDCS) use devices placed on the scalp to stimulate the cerebral cortex. These methods have shown efficacy in reducing pain, particularly in conditions like fibromyalgia and neuropathic pain. They are well-tolerated, non-invasive, and associated with minimal side effects. [46] [47]

Counterirritation involves relieving pain by inducing another, intense stimulus in the same or a different area of the body. Examples include:

TENS and PENS – Transcutaneous Electrical Nerve Stimulation and Percutaneous Electrical Nerve Stimulation use electrodes placed on or implanted into the skin to stimulate nerves. These methods may relieve chronic pain by activating nerve fibers that inhibit pain transmission. The comparison between PENS and TENS demonstrated the superiority of PENS, although the level of recommendation was low to moderate. Although evidence is mixed, they are widely used and beneficial for some patients.[48]

Capsaicin – A compound found in chili peppers, used in creams and patches. Initially causes burning, but with regular use, it desensitizes pain neurons. The method is safe and easy to apply. [41]

Heat and Cold – Provide immediate pain relief by relaxing muscles (heat) or reducing inflammation (cold). These are inexpensive, accessible, and safe methods [41].

Used in radicular pain and osteoarthritis of large and medium joints. Best results are seen when combined with multimodal therapy (e.g., physiotherapy). They offer short-term pain relief, but repeated injections may lead to cartilage volume reduction.[41]

Chronic pain is a problem faced daily by a vast number of people around the world. Unlike acute pain, which is a natural response of the body to injury or illness, chronic pain persists over a long period—weeks, months, or even years—and often does not subside despite treatment.These types of ailments significantly affect daily functioning, make it difficult to perform basic tasks, and, over time, may lead to social and occupational exclusion.

The consequences of chronic pain are felt not only by the patients themselves but also by healthcare systems and national economies. People struggling with pain are far more likely to use medical services, undergo pharmacological and rehabilitative treatment, and take sick leave or apply for disability pensions. All of this generates substantial financial and social costs, related among other things to reduced productivity and early withdrawal from the labor market [50].

Epidemiological studies show that chronic pain does not affect all social groups equally. There are clear differences based on gender-women report such ailments much more frequently than men. This difference amounts to as much as 11.1%, which may be due to both biological and psychosocial factors [50].

This phenomenon is particularly widespread in the countries of the European Union. Data indicate that nearly 44% of people aged 55 and older experience chronic pain, which significantly limits their activity and independence. Overall, the issue affects about 20% of adult Europeans [51]. Equally alarming are the statistics from the United States, where 1 in 5 adults reports chronic pain, equivalent to about 50.2 million people suffering almost daily [52] [53].

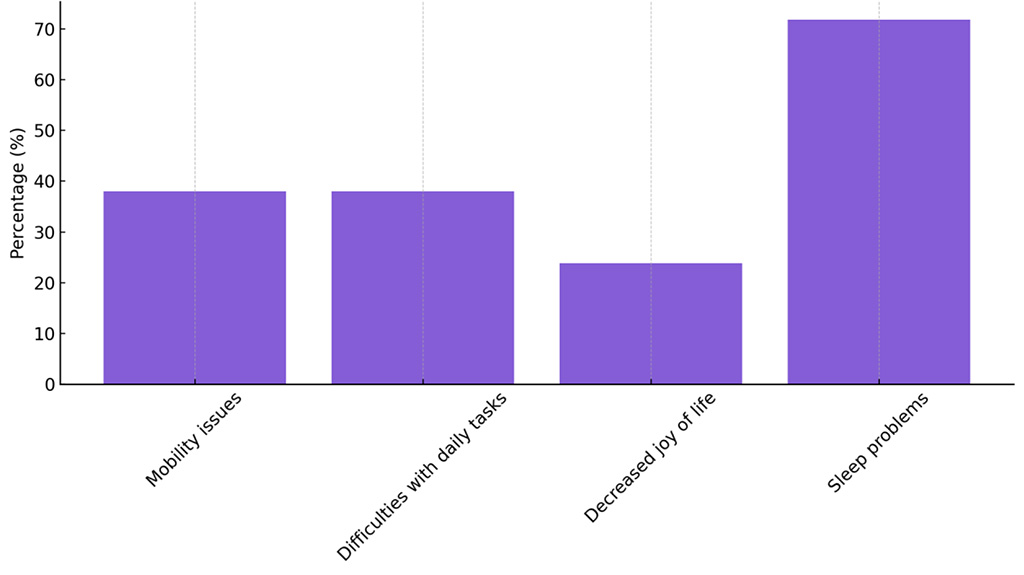

The impact of chronic pain extends beyond physical symptoms to include psychological and social dimensions. Approximately 38% of those affected report serious difficulties with mobility, which limits their independence and ability to move freely. The same proportion of respondents admitted that pain significantly hampers their ability to perform daily household duties and professional work. Moreover, nearly one in four individuals (23.9%) reported that chronic pain had diminished their sense of joy in life, highlighting its profound impact on emotional well-being and overall quality of life [50].

One of the most severe consequences of chronic pain is sleep disturbances. Sleep plays a key role in the body’s regenerative processes; its disruption quickly affects both physical and mental health. As many as 71.8% of individuals with chronic pain complain about difficulties falling asleep, interrupted sleep, and lack of rest [54]. These types of sleep disorders lead to increasing fatigue, reduced concentration, irritability, and a lowered pain threshold-which in turn exacerbates pain symptoms. This creates a vicious cycle in which pain and insomnia intensify each other, leading to further deterioration in health and quality of life. Chronic pain affects not only physical health but also daily functioning and psychological well-being. Chart 5 highlights the most commonly reported personal consequences experienced by patients.

Chart 5. Impact of Chronic Pain on Daily Functioning

In light of this data, it is clear that chronic pain is not merely a physical symptom but a complex issue requiring an interdisciplinary approach combining pharmacological treatment, psychological support, as well as rehabilitation and preventive measures. Proper diagnosis and integrated patient care can not only improve quality of life but also reduce the burden on healthcare systems and the economy as a whole.

Chronic pain represents a complex clinical and societal challenge due to its multifactorial pathogenesis, broad spectrum of clinical manifestations, and variability in treatment response. Despite a wide range of available therapies, both pharmacological and non-pharmacological, a significant proportion of patients continue to experience suboptimal outcomes. This highlights the limitations of monotherapy and the need for integrated, personalized care strategies.[29][41][42]

Pharmacological treatment remains the cornerstone of chronic pain management. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, weak and strong opioids, antidepressants, and anticonvulsants are commonly used, yet long-term efficacy and tolerability remain a concern. While recent advancements, such as sodium channel blockers (e.g., suzetrigine) or CGRP antagonists, offer promising new avenues, clinical adoption is still limited by cost, availability, and insufficient long-term data. Moreover, combination therapy and individualized drug selection based on pain mechanism and patient characteristics are often underutilized in routine practice.[34][36][37][41]

Non-pharmacological strategies—including physiotherapy, psychological interventions, and lifestyle modification—have gained recognition as essential components of multimodal pain therapy. These approaches target the biopsychosocial nature of pain and are especially effective in improving functionality and quality of life. Nevertheless, access to these services varies greatly across countries and healthcare systems, and evidence-based implementation remains inconsistent.[20][29][31][52]

Interventional pain management techniques, such as spinal cord stimulation, intrathecal drug delivery, and radiofrequency ablation, are typically reserved for patients with refractory pain. Although these methods show benefit in selected cases, they are invasive, costly, and supported by limited high-quality evidence. Further clinical trials and long-term studies are required to establish standardized protocols and patient selection criteria.[42][43][44][45]

The reviewed data confirm that chronic pain disproportionately affects older adults, women, and individuals with lower socioeconomic status. These disparities reflect both biological differences and systemic inequalities in access to care. Furthermore, the impact of chronic pain on quality of life, psychological well-being, and work productivity reinforces the importance of early diagnosis, preventive strategies, and patient education.[2][8][50][53]

A key limitation of current practice is the fragmented nature of care, which often lacks coordination between medical, psychological, and rehabilitative services. Integrated pain management programs, although shown to improve outcomes, are still not widely available. Moreover, while the literature supports the benefits of multidisciplinary approaches, implementation is frequently hindered by resource constraints and insufficient provider training.[29][42][51]

This review also highlights several gaps in the existing research landscape. These include a lack of large-scale comparative studies of combined pharmacological and non-pharmacological interventions, insufficient data on the long-term effects of new therapeutic agents, and underrepresentation of certain patient populations—such as the elderly, those with cognitive impairment, or individuals with chronic primary pain disorders.[18][21][30]

In addition, there is a pressing need to reform professional education and healthcare system organization to meet the growing burden of chronic pain. Medical training programs often devote insufficient time to pain management, particularly in areas such as psychosocial assessment, communication skills, and non-pharmacological therapies. As a result, clinicians may rely too heavily on pharmacological solutions, overlooking the broader context of the patient’s experience. To address this, curricula should incorporate interdisciplinary pain education based on the biopsychosocial model, while continuing medical education (CME) should emphasize evidence-based guidelines and shared decision-making. At the system level, chronic pain should be recognized as a distinct clinical domain, supported by structured care pathways, reimbursement models for multimodal interventions, and the development of specialized pain management centers. These reforms are essential for improving patient outcomes and reducing the long-term societal and economic costs associated with chronic pain.[1][29][35][42][51]

Chronic pain is a multifaceted condition that poses a major challenge to both individual health and public healthcare systems. Its high prevalence, complex pathophysiology, and significant impact on quality of life underscore the need for individualized, multidisciplinary management strategies. While pharmacological interventions remain central to treatment, their long-term effectiveness is limited, and adverse effects are common. Non-pharmacological therapies, including physiotherapy, psychological support, and lifestyle modification, are critical adjuncts that must be more widely integrated into routine care. Interventional procedures may offer relief for selected patients but require careful indication and further validation.

Effective management of chronic pain requires a paradigm shift toward personalized, multimodal approaches rooted in the biopsychosocial model. Education of healthcare providers, public awareness, and improved access to comprehensive pain services are key components of such reform. System-level changes—including the development of interdisciplinary care models, training programs, and reimbursement mechanisms—are necessary to ensure equitable and evidence-based treatment.

Future research should focus on:

By addressing these gaps, the medical community can move toward more effective, humane, and equitable treatment of chronic pain.

All authors have read and agreed to the final version of the manuscript.

The authors declare no conflict of interest.