- Home

- About the Journal

- Peer Review

- Editorial Board

- For Authors

- Reviewer Recognition

- Archive

- Contact

- Impressum

- EWG e.V.

Background: Infection prevention is essential for providing safe and quality facility-level services. Worldwide, morbidity and mortality are primarily due to preventable infectious diseases which account for 62% of all deaths in Africa and 31% in Southeast Asia. Therefore, infection prevention and control measures enhance the protection of vulnerable people.

Objective: The objective of this study is to determine infection prevention practice and associated factors among healthcare workers working in government health facilities of Mogadishu, Somalia, 2022

Methods: A quantitative cross-sectional study was conducted from March 01, 2022, to May 30, 2022 on 562 healthcare workers of public health facilities in Mogadishu town. After obtaining consent from the study participants, data was collected using pretested, self-administered, and standardized questionnaires adapted from other studies. After the data was collected, it was processed, cleaned, and analyzed using SPSS version 26. A logistic regression model was computed to measure the association between the predictor and outcome variables. A P-value of.05 with a 95% CI was used as the cut-off point to declare the level of statistical significance.

Results: The study found that 236 (42.4%) (95%CI: 1.38-1.47) of the 556 respondents had a good practice of infection prevention. In the multivariate logistic regression analysis, attitudes of health care workers toward infection prevention (AOR=0.478, 95 percent CI: 0.316, 0.723), occupational training (AOR:0.177, 95%CI:0.177,0.591), work experience of health care workers (AOR:3.215,95%CI:1.712,6.038), availability of infection prevention guidelines (AOR: 0.489,95%CI:0.284,0.842), budget availability for infection prevention (AOR: 0.421, 95%CI: 0.245,0.723) were among factors significantly associated with infection prevention practice.

Conclusion: The magnitude of infection prevention practice was low (42.4%) compared to other studies. The results of the study showed that attitude, knowledge work experience, training, needlestick injury, vaccination against HepB and other infectious diseases, availability of infection prevention guidelines, availability of hand rub in the room, and availability of budget for infection prevention were among factors associated with infection prevention practice.

Keywords: Infection prevention, healthcare workers, government health facility, Mogadishu, Somalia

Infection prevention is the process of creating barriers between vulnerable hosts and microorganisms and is essential for the delivery of safety and quality health services at the facility level. This also applies to all policies, procedures, and measures aimed at preventing or minimizing the risk of transmission of infectious diseases in the healthcare sector. The emergence of life-threatening infections such as acute respiratory syndrome and other infectious diseases has highlighted the need for effective infection control programs in all aspects of healthcare (1).

Morbidity and mortality in the world are mainly due to infectious diseases. Available data shows that most developing countries are affected by the epidemic, which accounts for 62% of all deaths in Africa and 31% in Southeast Asia. While this poses a threat to both healthcare workers and patients, infection prevention and control measures improve protection for those who are vulnerable to infection in the community (2).

Studies show that healthcare-associated infections (HAIs) are a global problem and represent a significant disease burden for patients and healthcare workers, especially in low- and middle-income countries and in resource-poor settings. HAI is an infection that occurs during healthcare in every healthcare facility and poses a serious threat to patients and healthcare workers. According to a WHO report, the prevalence of HAIs ranges from 3.5% to 12% in developed countries, compared to 5.7% and 19.1% in developing countries. On the other hand, 10% of hospitalized patients in developed countries and a quarter of patients in developing countries are infected with HAI, leading to prolonged hospital stays, increased economic burden and severe morbidity and mortality. Over 90% of these infections occur in developing countries and are burdened by the lack of standardized infection prevention programs due to limited resources and poor sanitation and hygiene practices (3–5).

However, healthcare-acquired infections associated with morbidity and mortality can be prevented through infection prevention strategies such as proper hand hygiene, implementation of standard precautions such as safety injections, isolation precautions, patient bathing, antibiotics, vaccination, environmental cleaning, disinfection and sterilization, comprehensive unit. Safety program and surveillance were the most important steps in infection prevention. It has been shown that 35-55% of HAIs are preventable (1,6).

Infection prevention practices are one strategy to address the challenges of HAIs. However, various studies have shown that while HAIs are preventable, the rate of infection among healthcare workers appears to be very low. The study, conducted at Gondar University Hospital, Ethiopia, found that the infection prevention practice status of healthcare workers was 57.4% and about a quarter (26.6%) of them had been exposed to needlestick/sharp injuries (7). A study conducted in rural and urban hospitals in Vietnam also found poor infection control practices in hospitals due to lack of resources, lack of awareness, and patient overload (8).

Therefore, this study aims to find more evidence of infection prevention practice and associated factors among healthcare workers working in government health facilities in Mogadishu, Somalia.

The practice of safe infection prevention plays an immeasurable role in saving the lives of healthcare workers and patients and determining the quality of care. Infection prevention measures are among the precautionary measures in the fight against COVID-19. Therefore, there is a need to review the current status of health workers' infection prevention practices, identify gaps and find solutions. However, there are no documented studies in Mogadishu on the practice of infection and related factors among healthcare professionals in healthcare facilities.

It is crucial to examine the practice of infection prevention and the factors involved among health workers in order to take the necessary steps and measures to protect and support these health workers and patients. This study will provide evidence of infection prevention practices and associated factors among health workers working in the Mogadishu.

In this research, factors associated to infection prevention are evaluated, conclusions are drawn, and further courses of action are determined. The findings of this study on infection prevention practices and associated factors among healthcare workers are critical to inform affected governmental and non-governmental organizations, heads of primary health care units, CEOs of hospitals and service providers, and county, provincial and regional health departments to help and the Health Office of the city as well as the Somali Minister of Health to take action to fill the gap identified in the study to design an appropriate infection prevention strategy for policy development, also it will be made available for reference to other interested researchers . It is also important that patients receive quality care. Ultimately, to save the lives of the people of Mogadishu and Somalia, the study will help provide guidelines for reducing disease, medical expenses and mortality.

Mogadishu, unlike other Somali regions, is considered a municipality rather than a federal state. It consists of 17 districts and 8 government health centers, 12 general hospitals, 12 referral hospitals and high number of private primary, secondary and tertiary health facilities. There are a total of 5,000 government employed health professionals. Of these healthcare workers, 3,400 were male and 2,600 were female. Private health facilities employed 7,000 health workers, 3,000 men, and 4,000 women.

A quantitative institution-based cross-sectional study design was used in this study, from March 01, 2022 to May 30, 2022. The following health facilities were involved in the study: public facilities of Madino hospital, Banadir hospital, S.O.S hospital maternity,Yardimeli specialist hospital, De Martino hospital and Keysaneey hospital.

a)

Source population

All

health professionals (healthcare officers, nurses, midwives,

laboratory technicians and technologists, public nurses, physicians,

pharmacists, radiologists, and anesthesiologists) working in

Mogadishu government health facilities were the baseline population.

b)

Study population

The

study population consisted of all HCWs selected by simple random

sampling technique from the selected state healthcare facilities.

a)

Inclusion criteria

All health professionals who work in government

health facilities of Mogadishu own administration and who have the

qualification of health Doctors, officers, physicians, midwives,

nurses, pharmacy, anesthesia, and laboratory personnel who were

working in the direct care of patients in Mogadishu government health

facilities were included.

b)

Exclusion criteria

Health

care workers who were ill and absent at the time of data collection

and on annual leave during data collection were excluded. Healthcare

professionals not directly involved in clinical service and not

exposed to HAIs were excluded from this study.

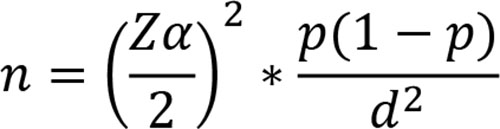

The sample size for this objective was calculated using a single proportion formula from governmental health care workers working in government health care facilities. With the assumption of 5% Margin of error and a 95% CI, Zα/2=Critical value = 1.96, 10% non-response rate and design effect =1.5. The assumption for P, for this study, was 50% since no similar published research has been conducted in the study area. So, the proportion of Infection prevention practice among government health care workers is assumed to be 50% based on this:

P (population proportion) = 50% Where n = required Sample size d= the margin error between the sample and the population = 0.05

The formula for single proportion was applied as follows using the following single proportion formula

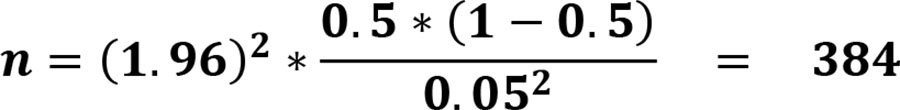

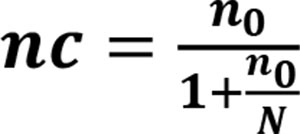

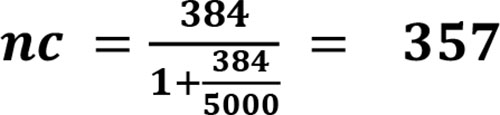

Now since the total sample size for the study is 384. According to the source from the Health Bureau of Mogadishu town central statistic, the total HCWs is 5000 which is <10,000 population.

Design effect (1.5) will be used Since we use a three-stage sampling technique (hierarchies), a 10% response rate will be considered. Now since the calculated sample size is < 10% of the Population, the Correction formula for a finite population is needed to be applied. Correction Formula for final sample size =

Where nc = Corrected sample n o = Sample size calculated

N= Population (in this case it is total HCWs in Mogadishu HFs)

there fore:

Final sample size = 357 *1.5 (design effect) * 10% = 590

Therefore, the Final sample size for the study is 590 Health care worke

Data was collected from study participants using a pre-tested structured questionnaire. The questionnaire was adapted from published studies with reasonable modifications. It contains variables on socio-demographic and socio-economic characteristics, characteristics related to health workers, characteristics related to health care facilities, questions about infection prevention practice, knowledge, and attitude questions. The questionnaire was prepared in English because the language is the working language of hospitals and healthcare professionals can answer the questionnaire in English. It was pre-tested by the trained data collectors on the participants at the same location outside of the surveyed healthcare facilities and revised before the actual data collection began. Data collection was carried out by 10 (ten) qualified data collectors (diploma holders) under the supervision of two supervisors, mainly health professionals with degrees and diplomas, and they received two-day training from the principal investigator on the aim of the study, how to fill in the questionnaire and how to maintain privacy and confidentiality during the interview.

Ten data collectors and two supervisors were trained for two days on the topics of data collection, data handling, data completion, data privacy, data completeness, consistency, etc. The pre-test was conducted in non-selected neighboring clinics of the study, ranging to 5% (30) of the respondents before the final data collection. Data quality was ensured by careful consideration of the relevance of the questionnaire to the study objectives. The correctness of the questionnaire in its content design and language was checked and modified according to the consultant's standards, comments and suggestions. The data collection process was reviewed daily by the supervisor and principal investigator for data completeness, accuracy and consistency, and corrective actions were taken.

Upon completion of data collection, they were entered into to Epi Info7 version 2.5 and then exported to SPSS version 26 for cleansing and analysis. Finally, descriptive analyzes such as frequency, percentage, and mean were used to describe the data. A binary logistic regression model was also applied to identify factors associated with infection prevention practice. Accordingly, the variables with the result of a p-value < 0.25 in the bivariable logistic regression analysis were considered for the multivariable logistic regression analysis. The adjusted odds ratio (AOR) with 95% confidence interval (CI) was used to measure the strength of the association, and the variable with a p-value < 0.05 was assumed to be statistically significant for multivariate logistic regression analysis.

Some of the very important terms are contextually defined below

1. Infection Prevention Practice: The infection prevention practices of HCWs were assessed for main components of infection prevention measures like hand hygiene practices, utilization of personal protective equipment (PPE), healthcare waste management practices, instrument decontamination, and disinfection practice. Each correct response was coded by "1" and incorrect "0". Correct values were summed up and the mean value was calculated. The mean value was used to classify HCWs infection prevention practices as having good practice if the score was equal to or above the mean. The same procedures were applied to assess knowledge by 6 yes or no questions and 8 choice questions (24)

For the convenience of analysis, each correct response in the knowledge category was scored 1 and each incorrect response will be 0. The correct response was obtained by summing up items scored and dividing by the total number of items and if it was above or equal to the mean (average) score was Good Knowledge and otherwise Poor Knowledge(23)

Attitude about Infection prevention Practice: Respondents will be asked attitude-related questions to describe their level attitude. subscale score will be obtained by summing up items scored and dividing by the total number of items, and if above or equal to the mean (average) score and it I was the positive attitude and otherwise a negative attitude (24).

Ethical approval of the study was obtained from the Research Ethical Review Committee of the Somali Federal Government, Ministry of Health and Human Services prior to proceeding with actual data collection under reference number MOH&HS/DGO/0287/March/2022. A formal letter was written to the Mogadishu Health Bureau and then to all selected health facilities in Mogadishu. Respondents were provided detailed information about the purpose, potential benefits and side effects, the right to continue or discontinue the interview, and the aim of the study, and were given consent to read for those who can read while the Interviewers read it for those who cannot read. Each respondent was assured that the information they provided would be kept confidential and used for academic research purposes only. The study was conducted on the basis of respondents' interest and they had the full right to withdraw from the study or refuse to complete any questionnaires at any time.

A total of 556 healthcare workers participated in the study with a response rate of 94%. 234 (42.1%) were men and 322 (57.9%) were women. The mean and standard deviation of the age of the study participants were both 27.29±5.854. The study found that more than two-thirds of respondents, 451 (81.1%), had a college degree and 76 (13.7%), 20 (3.6%), 9 (1.6%) had a degree, a Masters (MSC/MPH) and a Ph.D. The marital status of the respondents showed that 318 (57.2%) of the study participants were single, 222 (39.9%) were married and 16 (2.9%) were divorced. Of these, 353 (63.5%) had less than 10 years of professional experience and 203 (36.5%) had more than 10 years of professional experience. The study showed that 436 employees (78.4%) had a monthly income of less than three thousand US dollars (US$3,000) and the average annual income of the participants was US$1,594.3 (Table 1).

Table 1: Socio-demographic & economic Characteristics of Respondents, Mogadishu public health facilities , 2022

| Attributes | Categories | Frequency | Percent (%) |

| Sex | Male | 234 | 42.1 |

| Female | 322 | 57.9 | |

| Age | Age group 20-29 | 59 | 10.6 |

| Age group 30-39 | 342 | 61.5 | |

| Age group 40-49 | 93 | 16.7 | |

| Age group 50-59 | 60 | 10.8 | |

| Age group 60 and above | 2 | .4 | |

| Educational status | Degree | 451 | 81.1 |

| Diploma | 76 | 13.7 | |

| MSC/MPH | 20 | 3.6 | |

| Ph.D. | 9 | 1.6 | |

| Marital status | Single | 318 | 57.2 |

| Married | 222 | 39.9 | |

| Divorced | 16 | 2.9 | |

| Monthly income | Monthly Salary ≤ 3000 USD | 436 | 78.4 |

| Monthly Salary 3001-5000 USD | 113 | 20.3 | |

| Monthly Salary >5000 USD | 7 | 1.3 | |

| Work Experience | Health Professionals Work Experience with Less than and 10years | 377 | 63.5 |

| Health Professionals Work Experience with above 10years | 203 | 36.5 |

Infection prevention practice status of Health workers working in public health facilities of Mogadishu

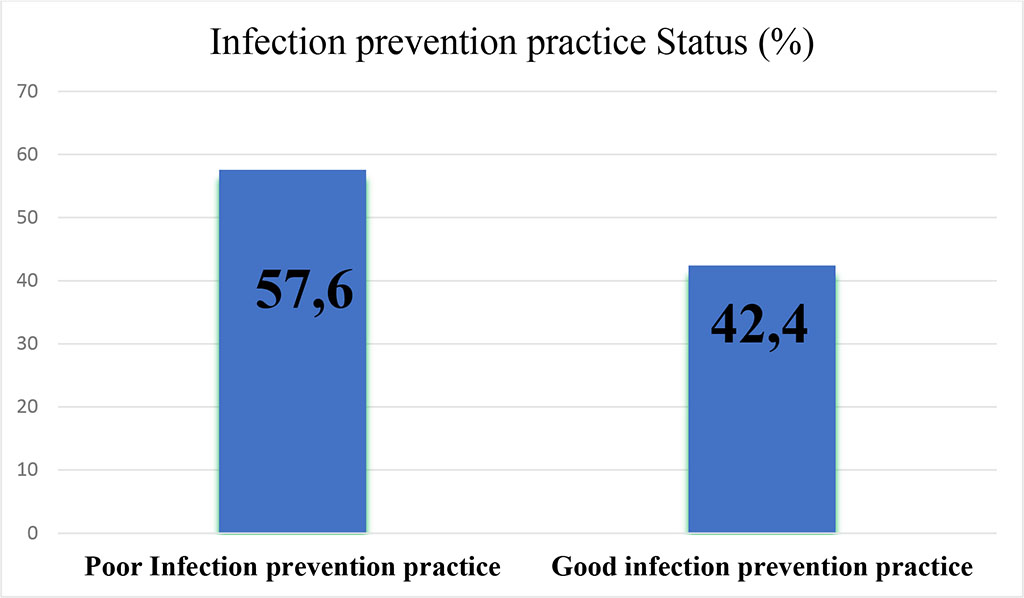

The study found that 236 (42.4%) (95% CI: 1.38-1.47) of the 556 respondents among health workers working in public health facilities in Mogadishu, Somalia, had good infection prevention practices (Fig.1).

Figure 1: Infection Prevention Status among Health workers working in public health facilities of Mogadishu, Somalia, 2022

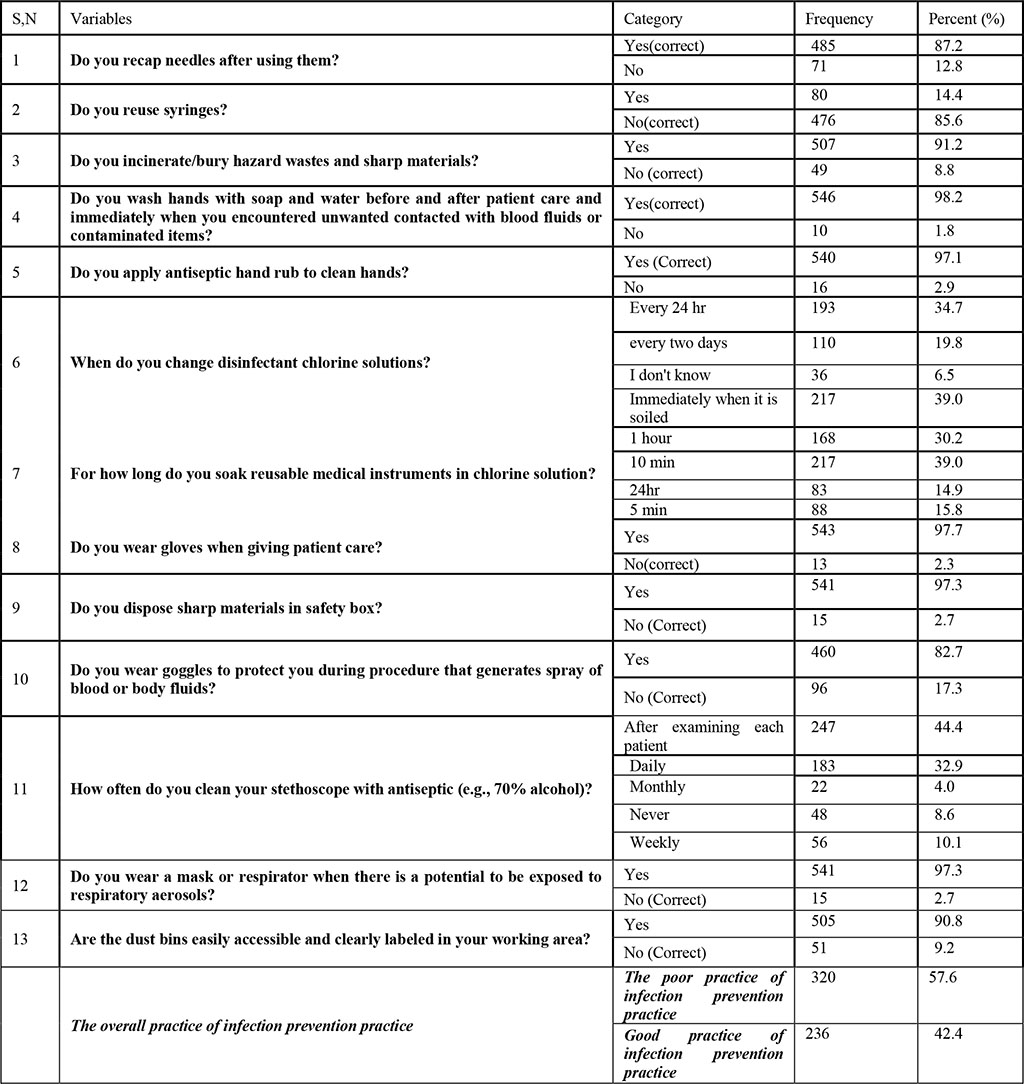

Thirteen practice-based infection prevention questions were used to assess the status of infection prevention practice among health workers working in public health facilities of the city of Mogadishu. Based on responses to the infection prevention questions, the majority of healthcare workers 485 (87.2%) responded that they recap needles after use, while the remaining 71 (12.8%) did not (Table 2).

In the practice of infection prevention, syringe reuse is one of the factors critically exposing healthcare workers to HAIs. In this finding, more than three-quarters of study participants, 476 (85.6%), reported that they did not reuse syringes, but in contrast, very few 80 (14.5%) of healthcare workers reported that they did Syringes reused (Table 2).

Hazardous waste should be disposed of and incinerated in hospitals to protect both healthcare workers and patients from HAIs. In this study, the majority of respondents (507.91.2%) confirmed that they burn/bury hazardous waste and sharp materials, while the others (49.8.8%) do not bury hazardous waste (Table 2).

Medical personnel should wash their hands before and after each patient care and immediately after unwanted contact with blood fluids. This was one of the questions health workers were asked to explain their handwashing practice. Respondents responded that almost all, 546 (98.2%), practiced hand washing during and after patient contact, and 10 (1.8%) of healthcare workers said they did not (Table2).

In infection prevention, the application of hand rub to clean hands is very important to kill microorganisms that expose healthcare workers. In this study, responses from healthcare professionals indicate that the majority of them 540 (97.1%) used an antiseptic hand rub to clean their hands, but very few respondents 16 (2.9%) did not use it (Table2).

Handling the chlorine solution and changing it within 24 hours is recommended as good practice for infection prevention. Health workers were asked to indicate how often they change the disinfectant chlorine solutions. According to these results, one hundred and ninety-three (34.7%) health workers change the disinfecting chlorine solution every 24 hours, which is the standard. However, 110 (19.8%) of healthcare workers change every two days, 217 (39%) change immediately when soiled, and the rest of respondents 36 (6.5%) said they didn't know. On the other hand, when asked how long do they soak reusable medical instruments in chlorine solution, healthcare professionals responded. Some of them 168 (30.2%) soak reusable medical instruments in the chlorine solution for one hour, while the other 217 (39%), 83 (14.9%), 88 (15.8%) soak reusable medical instruments 10 minutes, 24 hours or 5 minutes respectively (Table 2).

In this study, responses from study participants indicated that 543 of 556 respondents (97.7%) wear gloves when caring for patients, while 13 (2.3%) did not. On the other hand, 541 (97.3%) responded that they dispose of sharps in security boxes, while 15 (2.7%) did not. The majority of them (460.82.7%) wear goggles to protect themselves from blood or body fluid splashes during the procedure and their colleagues (96 (17.3%) did not use them. On the other hand, health workers were interviewed to say how often they clean their stethoscope with an antiseptic and some of them (247.44.4%) said they disinfect it after examining each patient, 183 (32.9%) of them said they disinfect them daily, while the other 22 (4%), 48 (8.6%), 56 (10.1%) indicated that they disinfect monthly, never disinfect, and disinfect weekly, respectively(Table2).

On the other hand, as they are in the period of the COVID-19 pandemic, study participants were also asked if they wear a face mask that is not exposed to respiratory aerosols, and the majority of study participants, 97.3% (541), wear it a mask and 15 (2.7%) did not (Table2).

To prevent infection, dust bins should be easily accessible and clearly marked in medical staff work areas. It was highlighted in this study that 90.8% (505) of the respondents indicated that bins are easily accessible and marked, the others (51.9.2%) assured that bins are not accessible and clearly marked in their work area.

Table 2: Practice of Infection prevention practice status of health workers working in public health facilities of Mogadishu, Somalia ,2022

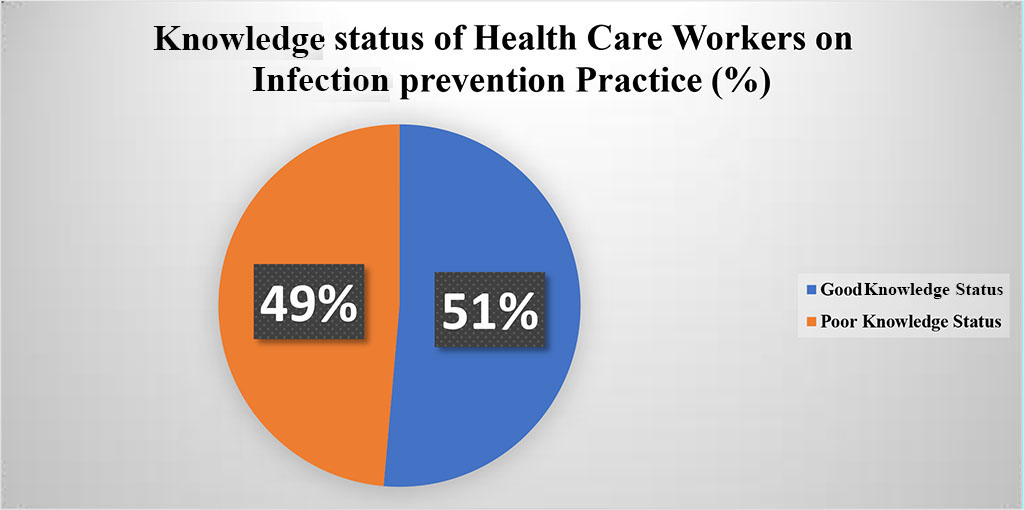

Five (5) knowledge-related questions were used to measure respondents' level of knowledge about infection prevention practice. Respondents' overall knowledge of infection prevention practice was rated as good for those responding above the mean and poor for those responding below or equal to the mean. According to the results, 270 (49%) of all respondents had a low knowledge of infection prevention practice, while 286 (51%) had a good knowledge (Fig 2).

Figure 2: Knowledge status of health workers working public health facilities of Mogadishu town ,Somalia,2022

Respondents were asked to rate their understanding of handwashing with soap or alcohol-based antiseptics to reduce the risk of transmitting hospital-acquired pathogens, and the majority of them, 539 (96.9%), were aware of the use of soap or alcohol-based antiseptics reduced the risk of hospital-acquired pathogens, while few of them, 17 (3.1%), were unaware (Table 3).

Respondents were also asked to name their most preferred handwashing methods to kill microorganisms, and more than half of the respondents, 360 (64.7%), chose washing hands with alcohol as the most common way to kill microorganisms, and some of them, 73 (13.1%) selected iodine solution as the preferred method, while the other 123 (22.1%) said soap and water was the more preferred hand washing method to kill microorganisms (Table 3).

On the other hand, the level of knowledge of medical professionals on how to prepare chlorine solution was examined and more than two thirds of them 485 (87.2%) knew the formula to prepare 0.5% chlorine solution and the residues, whereas 71 (12.8%). did not know (Table 5).

The safety box is very important to collect needlesticks and syringes after use and should be three-quarters full and burned according to the standard. Health workers were also asked to indicate their level of knowledge of the level to which security boxes should be filled prior to locking and sealing. However, the majority of them, 287 (51.6%), incorrectly answered that security boxes should be completely filled. The other 181 (32.6%) replied that it should be half full (1/2). Only 88 (15.8%) of respondents answered this question correctly, stating that security boxes should be three-quarters (3/4) full and sealed (Table 3).

On the other hand, the level of knowledge of healthcare professionals regarding the disease transmitted through needlestick injuries, and the majority of respondents 357 (64.2%) responded that HIV and HBV are the two most common diseases transmitted through needlestick injuries. The other 106 (19.1%) said that only HBV is transmissible through needlestick injuries, and 57 (10.3%) of them said HIV is the disease transmitted through needlestick injuries. Others chose HIV and TB (9.1.6%) and some of them21 (3.8%) said HIV, HBV, and TB were transmissible through needlestick injuries while few of them said TB (0.7%) was one needle-borne disease stick injuries (Table 3).

Table 3: Knowledge about infection prevention practice of health workers working in public health facilities of Mogadishu, Somalia,2022

| Variables | Category | Frequency | Percent (%) |

Washing your hands with soap or an alcohol-based antiseptic decreases the risk of transmission of hospital-acquired pathogens |

No |

17 | 3.1 |

| Yes | 539 | 96.9 | |

| Which is the more preferred hand washing method to kill microorganisms? | Alcohol hand rub | 360 | 64.7 |

| Iodine solution | 73 | 13.1 | |

| Water and soap | 123 | 22.1 | |

| Do you know the formula for preparing 0.5% chlorine solution? | No | 71 | 12.8 |

| Yes | 485 | 87.2 | |

| Do you know to what level safety boxes should be filled before closing and sealing? | Full | 287 | 51.6 |

| One half (1/2) | 181 | 32.6 | |

| Three fourth (3/4) | 88 | 15.8 | |

| Which of the following disease is transmitted by needle stick injury? (More than one answer is possible) | HBV | 106 | 19.1 |

| HBV and TB | 2 | .4 | |

| HIV | 57 | 10.3 | |

| HIV and HBV | 357 | 64.2 | |

| HIV and TB | 9 | 1.6 | |

| HIV;HBV;TB | 21 | 3.8 | |

| TB | 4 | .7 | |

| Overall Knowledge Score of health workers toward infection prevention practice | Poor Knowledge of health workers toward infection prevention practice | 270 | 48.6 |

| Good Knowledge of health workers toward infection prevention practice | 286 | 51.4 |

Attitudes of healthcare professionals towards infection prevention were measured using five-point items on the Likert scale (strongly disagree, disagree, neutral, agree, and strongly agree) ranging from one (1) to five (5) were coded. The mean score was determined, and those responding below or equal to the mean score were scored as negative, while those responding above the mean score were scored positive (Table 4).

After the procedure, the study found that 207 people (37.2%) had positive attitudes towards infection prevention practice, while 349 people (62.8%) had negative attitudes towards infection prevention practice. When healthcare workers' attitudes were assessed on whether they agreed that washing hands with soap or alcohol-based antiseptics reduced the risk of transmission of HAIs, a majority of them agreed 398 (71.6%), 89 (16%) of they strongly agreed, 10 (1.8%) strongly disagreed, 11 (2%) and 48 (8.6%) responded neutrally to the question (Table4).

They were asked about their attitude towards protective gloves and 15 (2.7%) strongly disagreed that gloves offer complete protection against infection transmission, 29 (5.2%) disagreed, 50 (9%) neutrally and one Majority of 370 (66.5%) agreed that gloves offer full protection and 92 (16.5%) of them strongly disagreed (Table4).

On the other hand, study participants were asked whether they agreed that used needles should be recapped immediately after injection to avoid accidental injury. Up to this point, 22 (4%) strongly disagreed, 17 (3.1%) disagreed, 40 (7.2) neutrally, 368 (66.2%) agreed, and 109 (19.6%) strongly agreed that used needles should be recapped to avoid accidental injury (Table 4).

The other question was knowing the attitudes of healthcare workers, whether using gloves when in contact with patient care is a useful strategy to reduce the risk of transmission and 11 (2%), 10 (1.8%), 28 (5%) , 382 (68.7%), 125 (22.5%) strongly disagree, disagree, neutral, agree and strongly disagree. On the other hand, respondents were asked if they were at low risk of getting infections from patients and 12 (2.2%), 53 (9.5%), 206 (37.1%), 200 (36%), 85 (15.3%) were strongly disagree, disagree, neutral, agree and strongly disagree that there is a very low risk of infection in patients (Table 4).

Table 4: Attitudes of Health care workers toward Infection prevention practice ,2022

| Variables | Strongly disagree | Disagree | Neutral | Agree | Strongly agree | |||||

| N | % | N | % | N | % | N | % | N | % | |

| Do you agree that washing hands with soap or an alcohol Based antiseptic decreases the risk of transmission of hospital-acquired infections | 10 | 1.8 | 11 | 2.0 | 48 | 8.6 | 398 | 71.6 | 89 | 16.0 |

| Gloves provide complete protection against acquiring/transmitting infection | 15 | 2.7 | 29 | 5.2 | 50 | 9.0 | 370 | 66.5 | 92 | 16.5 |

| To prevent accidental injury, used needles should be recapped immediately after use | 22 | 4.0 | 17 | 3.1 | 40 | 7.2 | 368 | 66.2 | 109 | 19.6 |

| Using Gloves during patient care contacts is useful strategy for reducing the risk of Transmission | 11 | 2.0 | 10 | 1.8 | 28 | 5.0 | 382 | 68.7 | 125 | 22.5 |

| You have a very low risk of acquiring infections from your patients | 12 | 2.2 | 53 | 9.5 | 206 | 37.1 | 200 | 36.0 | 85 | 15.3 |

| Attitude Score of Employees toward facemask utilization | Negative Attitude of HCWs toward Infection prevention practice | 349 |

62.8% |

|||||||

| Positive Attitude of HCWs toward Infection prevention practice | 207 |

37.2% |

||||||||

Bivariate logistic regression and multivariable analysis were carried out to determine independent predictors of facemask utilization. Those candidate variables with a P-value < 0.25 in bivariate logistic regression were included in the multivariable logistic regression model and considered significant in the model at a P-value less than 0.05(Table 5).

A result of bivariate logistic regression applied to identify significant independent variables showed that infection prevention was significantly (P<0.25) associated with attitude, knowledge, work experience, training, needlestick injury, vaccination against HepB and others, the availability of infection prevention guidance, it was found that the availability of hand rub in the room, the availability of infection prevention budgets, the monthly salary, the availability of the infection prevention committee, the availability of PPE, the availability of Hand washing facilities and the availability of incinerators are significantly associated with infection prevention (Table 5).

However, in the multivariate logistic regression analysis, attitude, knowledge, work experience, training, needlestick injury, vaccination against HepB and others, availability of infection prevention guidelines, availability of hand rub in the room, and availability of budget for infection prevention were found to have a significant association with infection prevention practice (Table 5).

The study found that healthcare workers with negative attitudes towards infection prevention were 52.2% less likely to practice infection prevention (AOR = 0.478, 95% CI: 0.316, 0.723) than those with positive attitudes (Table 6). Similarly, the study showed that healthcare workers with low infection prevention knowledge were 63% less likely to take infection prevention practices (AOR = 0.163, 95% CI: 0.099, 0.270) than those with high infection prevention knowledge (Table 5).

On the other hand, it was found that healthcare workers who were not fully vaccinated against HepB virus were 43% less likely to take infection prevention measures (AOR: 0.566, 95% CI: 0.366, 0.875) than those who were fully vaccinated against HepB -Virus were vaccinated HepB and others. In addition, those who had ever practiced a needlestick injury were 44% less likely (AOR: 0.560.95% CI: 0.390, 0.806) to practice infection prevention than those who had never had a needlestick injury (Table 5).

Regarding professional training, it was found that those who had not received professional training in infection prevention practice were 68% less likely to practice infection prevention (AOR: 0.177, 95% CI: 0.177, 0.591). compared to those who received an infection prevention practice. The study results also show that health workers with less than or equal to 10 years of professional experience are 3.215 times more likely to practice infection prevention (AOR: 3.215, 95% CI: 1.712, 6.038) than health workers with more than 10 years (Table 5).

In this study, it was found that the availability of infection prevention guidelines is one of the organizational factors related to infection prevention practice. On this basis, health workers without infection prevention guidelines practiced 51.1% less infection prevention (AOR: 0.489.95% CI: 0.284, 0.842) compared to health workers working in health care facilities where infection prevention guidelines were available (Table 5).

On the other hand, the finding of this study highlighted that the availability of hand rub in the working rooms of health workers was also an organizational factor associated with the low infection prevention practice. Following this, the study shows that the odds of infection prevention practice where there was no hand rub in the room were 78.8% less likely to practice infection prevention (AOR:0.212, 95%CI,0.047,0.955) when compared to those health workers working in where there was hand rub in their room (Table 5).

It is well known that budget availability is key to improving infection prevention practice. This study also ensured that health workers working in facilities that did not have an allocated budget for infection prevention practice were 57.9% less likely to practice infection prevention compared to health workers working in health facilities (AOR: 0.421, 95% CI : 0.245, 0.723) allocated budget for infection prevention practice.

Table 5: Multivariate analysis of Factors Associated with infection prevention practice among health care workers working in public health facilities in Mogadishu, 2022

| Variables | Category | Infection Prevention Practice Status | COR (95% CI) | AOR (95%CI) | P-value | ||

| Poor Infection Prevention Practice Status | Good Infection Prevention Practice Status | ||||||

| HWs fully vaccinated for Hep. B, other | Not fully Vaccinated(0) | 92 (28.7%) | 39(16.5%) | .595[.382, .927] | .566[.366, .875] | 0.022 | |

| Fully Vaccinated(1) | 228(71.3%) | 197(83.5%) | |||||

| ever had a needle stick injury | No | 151(47.2%) | 73(30.9%) | .616[.425, .892] | .560[.390 , .806] | 0.010 | |

| Yes | 169(52.8%) | 163(69.1%) | |||||

| Received occupational training on Infection Prevention | No | 63(19.7%) | 15(6.4%) | .323[.177, .591] | .323[.177, .591] | 0.000 | |

| Yes | 257(80.3%) | 221(93.6%) | |||||

| Work Experience of Respondents | <= 10 years | 201(62.8%) | 152(64.4%) | 3.215[1.712, 6.038] | 3.215[1.712, 6.038] | 0.000 | |

| >10 years | 119(37.2%) | 84(35.6%) | |||||

| Attitude status of HCWs | Negative attitudes of HCWS | 218(68.1%) | 131(55.5%) | .478[.316, .723] | .478[.316 , .723] | 0.000 | |

| Positive attitudes of HCWs | 102(31.9%) | 105(44.5%) | |||||

| Knowledge status of HCWs | Poor knowledge | 188(58.8%) | 82(34.7%) | .163[.099, .270] | .163[.099, .270] | 0.000 | |

| Good Knowledge | 132(41.3%) | 154(65.3%) | |||||

| Availability of infection prevention guideline | No | 60(18.8%) | 22(9.3%) | .445[.265, .750] | .489[.284 , .842] | 0.10 | |

| Yes | 260(81.3%) | 214(90.7%) | |||||

| Availability of hand rub in the room | No | 17(5.3%) | 2(0.8%) | .152[.035, .666] | .212[.047 , .955] | 0.043 | |

| Yes | 303(94.7%) | 234(99.2%) | |||||

| Availability of budget for infection prevention practice | No | 69(21.6%) | 22(9.3%) | .374[.224, .625] | .421[.245 , .723] | 0.002 | |

| Yes | 251(78.4%) | 214(90.7%) | |||||

The practice of infection prevention is important to delivering quality service and essential to protecting healthcare workers, patients and communities from infectious agents. This study attempted to assess the infection prevention practice of HCWs in Mogadishu. The study found that 236 (42.4%) (95% CI: 1.38-1.47) of the 556 respondents had good infection prevention practice among health workers working in Mogadishu's public health facilities. The results were lower compared to the systematic study conducted in Iran among dentists and showed that about 60% of them showed an adequate practice of infection prevention (34). The result is also lower than that of the study conducted among Palestinians, where most nurses (91.1%) had good infection prevention practices (39). On the other hand, this study was also lower compared to the study conducted in a public health facility in Addis Ababa, where 66.1% of healthcare workers were good at practicing infection prevention. The finding stands below the other study in Trinidad and Tobago, which found that 44% of healthcare workers are using best practice to prevent infection (14,18,19).

However, it was higher than the study conducted in Iran, which was found to be 8.7% (35). And the other study conducted and reported at Alansar General Hospital, Kingdom of Almonarawa, Saudi Arabia (24.6%) (37). Differences in practice could be due to the different periods of study; Experiences of HCW, area of study, and type of healthcare facilities from which HCW were selected to participate in the study.

This study also found that the knowledge level of health workers on infection prevention practice in the public health facility in Mogadishu was 286 (51%). This study result is higher than the study evaluating KAP in relation to infection prevention among health workers in Trinidad and Tobago, which reported 20.3% of infection prevention practice. The result is also higher compared to the study conducted in Kenya, which found that only 17.8% of health workers work at Mbagathi District Hospital (68). It is also higher compared to the study conducted in Iran, which reported a low knowledge rate of HCWS regarding infection control practices (1.5% of HCWS had low knowledge of IP practices (35). However, the result is lower than that of the study conducted at Hawler Teaching Hospital in the city of Erbil, where about 54% of nurses had a good knowledge of infection prevention measures (69).

On the other hand, it is also lower compared to the study conducted among Palestinians, where the nurses (53.9%) had an adequate knowledge of infection prevention practices (39). It is lower compared to Saudi Arabia, the study conducted on KAP from nurses towards IP in tertiary hospitals and found that 60% of nurses had a good knowledge of infection control measures (36). The discrepancy could be due to the difference between the study setting, the geographic location of the study, the difference in study time, the sample size, and the different healthcare systems between countries.

Regarding health-care workers' attitudes towards infection prevention practice, the study found that 207 health-care workers (37.2%) had positive attitudes towards infection prevention practice, while 349 people (62.8%) had negative attitudes towards infection prevention practice. This result is lower than the study conducted in the city of Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, which ensured that more than 80% of health workers had good attitudes towards infection prevention practice (14) and the study conducted in Egypt, Mina University Hospital and Mina General One hospital that reported 85% of HCWs at Mina University and 82% in general hospitals had a positive attitude towards IPP(68). On the other hand, the study is also lower than the systematic study conducted in Iran among dentists, which indicated a positive attitude towards infection prevention, which was >70% (34), and the study conducted among health workers in Trinidad and Tobago healthcare workers (46.7%) with a good attitude towards infection prevention practice and 55.6% of HCWs have a good attitude in Bahirdar Town, Ethiopia (57.71). The discrepancy could result from differences in the time, place, and sample size of the studies, as well as differences in the attitudes of healthcare workers.

In terms of professional training, the study showed that those who had not received professional training in infection prevention practice were 68% less likely to practice infection prevention (AOR: 0.177, 95% CI:0.177, 0.591) compared to those who received an infection prevention practice. This result differs from the study conducted in north-eastern Ethiopia, where healthcare providers who were trained in infection prevention were 2.2 times more likely to have good practice than those who were not trained (59). The difference could be due to differences in accessibility to vocational training, organizational commitment to building the capacity of their workers, time and geographic factors.

In this study, it was found that the availability of infection prevention guidelines is one of the organizational factors associated with infection prevention practice. On this basis, health workers working where there is no infection prevention guideline practiced 51.1% less infection prevention (AOR: 0.489.95% CI: 0.284, 0.842) compared to health workers working in health facilities working there Infection prevention guideline was in place. This study, in contrast to the study conducted in Ethiopia, shows that HWs who have had access to IP guideline have almost three times better chances of being proficient compared to the corresponding HWs (42,59,65). It's also not consistent with other studies where healthcare providers who have IP guideline in their healthcare facilities were 3.7 times higher than those who did not have IP policies and the study conducted in Addis Ababa, health care workers who were aware of the availability of infection prevention related standard operating procedures (SOPs) or guidelines in their healthcare facility were almost twice as likely to have good infection prevention practices in place as those who were not aware of the availability of infection prevention SOPs. The discrepancies could be due to the different availability of infection prevention guidelines and SOP, study time, and differences in sample size

The results of this study also showed that health workers with less than or equal to 10 years of professional experience were 3.215 times more likely to practice infection prevention (AOR: 3.215, 95% CI: 1.712, 6.038) than health workers with more than 10 years. This result was almost identical to the study conducted in Addis Ababa, which found that HCWs of less than 10 years were almost 4 times more likely to practice IP than those with more than 10 years of experience (23,24,57,58 ). This may be due to the fact that newly hired healthcare professionals have access to the updated knowledge and guidelines of infection prevention practice, and they are very energetic in applying infection prevention practice compared to those with more than 10 years of professional experience.

Compared to previous studies, the level of proper practice of infection prevention among health care workers working in the study area was low (42.4%). The results of the study showed that attitude, work experience, training, needlestick injury, vaccination against HepB and others, availability of infection prevention guidelines, availability of hand rub in the room, and availability of infection prevention budget were significantly related to these factors and infection prevention practice. Affected bodies should work hard to improve infection prevention measures by training medical staff in infection prevention practice to fill the training gap, and trained health workers sharing experiences for those who have not completed training, guidance use, allocate budgets for infection prevention practice, use of PPE, use of hand rub, and encourage HCWs to implement infection prevention practices.

The data used to support the findings of this study are available and can be accessed from the primary author on reasonable request.

Strength of the study: This research can help health professionals, hospital CEOs, health service managers, the Ministry of Health, and other sectors to focus on infection prevention and related issues. Because the information was collected by healthcare workers, it helps improve infection prevention strategies. Data were collected from trained government health workers who voluntarily completed a self-administered questionnaire. Data collection and data entry were strictly supervised, and analysis and cleanup were carefully performed using the latest versions of computer applications, SPSS version 26.

Limitation of the study: The study aimed to determine all aspects related to infection prevention practice but was not exhaustive and other factors might exist that were not discovered in this study. Some associated factors could not be compared to other studies due to the lack of similar studies. The other drawback of the study is that there were not enough comparable studies in Somalia and the study area to use as a literature review and therefore it was too difficult to make comparisons. Since the study only included government health facilities and health workers working in these facilities, not private health facilities and the health professionals working in them, this may limit the inference to the general health workers in Mogadishu.

The authors state that the research was conducted without commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

The authors contributed significantly to the work of this study and the correspondent participated in its drafting, revision/review. All authors agree to be responsible for the content of the work. The agreement was made with the journal to which the article was sent for publication.

I acknowledge RUDN University for initiating my work at this research. My gratitude goes to Somali Federal Republic, Ministry of Health and Human Services encouraging me and providing me Ethical approval. I am also grateful to Hagarla Institute and their team, my special thanks go to all my data collectors, Supervisors, Respondents, and co-workers.

No funded raised from institutions or other sources and the study was conducted by the researchers.