- Home

- About the Journal

- Peer Review

- Editorial Board

- For Authors

- Reviewer Recognition

- Archive

- Contact

- Impressum

- EWG e.V.

Cite as: Archiv EuroMedica. 2025. 15; 5. DOI 10.35630/2025/15/Iss.5.507

Background: Tranexamic acid (TXA) is increasingly important in prehospital care in Poland, particularly after the expansion of paramedic competencies introduced by the Regulation of the Minister of Health (March 7, 2024; Journal of Laws 2024, item 380). TXA’s antifibrinolytic properties help stabilize clots and reduce bleeding in trauma patients.

Objective: This narrative review analyzes the introduction of TXA into paramedic competencies in Poland and its potential impact on prehospital emergency care. It summarizes current literature on TXA use in prehospital trauma management and does not present original research data.

Methods: A narrative review of scientific literature, legal regulations, and prehospital emergency protocols was conducted. Key studies, including CRASH-2 and CRASH-3, were examined, alongside available Polish data on TXA administration and clinical use.

Results: Evidence confirms that TXA reduces trauma-related mortality, limits massive hemorrhage, and improves outcomes in traumatic brain injury. Polish regulations and protocols align with international recommendations, supporting the safe and evidence-based use of TXA by paramedics.

Conclusions: Expanding paramedic competencies to include TXA represents a significant advancement in Polish emergency medicine. Wider implementation requires ongoing training, standardized protocols, and systematic evaluation to optimize patient safety and treatment outcomes in prehospital trauma care.

Keywords: emergency medical services, tranexamic acid, TXA, prehospital care, massive bleeding, CRASH-2, CRASH-3, emergency medicine, trauma treatment

Emergency medical services in Poland are currently undergoing dynamic development, including both technological advancements and the gradual expansion of medical personnel competencies. The prehospital care system has evolved in response to societal needs, an increased number of traffic accidents, mass injuries, and medical complications requiring immediate intervention. In recent years, ambulance equipment has been modernized with advanced defibrillators, ventilators, and teletransmission devices, while paramedics’ qualifications have systematically improved [1].

Recent regulations have extended the scope of paramedics’ competencies, allowing them to perform additional medical procedures and administer selected medications, including tranexamic acid (TXA), in prehospital care [1, 2, 4]. These changes enable faster, independent intervention in life-threatening situations, where immediate access to a physician may not be possible.

TXA is particularly important in modern prehospital emergency care. As a synthetic lysine analog, it acts as an antifibrinolytic by inhibiting the conversion of plasminogen to plasmin, stabilizing clots, and reducing blood loss [3]. It is used in trauma-related bleeding, gastrointestinal, gynecological, and urological hemorrhages, as well as bleeding associated with fibrinolytic therapy. Its safety, efficacy, and ease of administration make TXA a first-line tool in the prehospital management of massive hemorrhage [4].

Numerous studies, including the CRASH-2 and CRASH-3 trials, have shown that early administration of TXA significantly reduces trauma-related mortality and bleeding complications, especially within the first three hours after injury [5, 6] Based on available data, approximately 30,000 deaths related to injuries occur annually in Poland, of which 6–7 thousand are victims of road accidents. Hypovolemic shock, resulting from massive bleeding, is one of the main causes of death in the prehospital and early hospital phase [13].

Traumatic brain injuries are the most common cause of death and long-term disability in people under 25 years of age. The incidence of these injuries increases due to traffic accidents, and their coexistence with other bodily injuries increases the risk of mortality.

.In mass casualty incidents (MCIs), early administration of TXA by competent paramedics is essential for stabilizing patients with severe bleeding and improving overall emergency response efficiency. Its low cost and options for intravenous and intramuscular administration further enhance its practicality in the Polish healthcare system [3, 4].

The development of paramedics’ competencies in the use of TXA represents a significant step toward increasing prehospital emergency care effectiveness, improving patient safety, and optimizing critical medical procedures. This paper presents TXA’s mechanism of action, indications, pharmacokinetics, routes of administration, dosage, contraindications, and a review of clinical studies, while discussing its importance in both mass incidents and routine paramedic practice

The objective of this study is to evaluate the efficacy, safety, and organizational significance of tranexamic acid (TXA) in Polish prehospital care [1]. Particular attention is given to TXA’s mechanism of action, clinical indications, pharmacokinetics, and routes of administration in emergency medical settings, including mass casualty incidents (MCI) [2].

The study reviews scientific literature on the effectiveness of TXA in reducing trauma-related mortality and massive bleeding, including international studies such as CRASH-2 and CRASH-3, as well as research evaluating the safety and efficacy of intramuscular administration [3, 4]. This analysis supports recommendations for incorporating TXA into standard emergency procedures and assessing its potential clinical and organizational benefits in prehospital care [5]. The practical goal of the study is to provide knowledge that may guide the development of guidelines for the availability of TXA in ambulances, in prefilled syringes, and in triage protocols during MCI, potentially enhancing rescue efficiency, improving patient survival, and minimizing complications from massive bleeding [6, 7, 13, 14, 25].

This study was developed using methods including a review of scientific literature, analysis of legal regulations, and evaluation of current prehospital emergency protocols [1]. Inclusion criteria comprised studies on TXA use in traumatic bleeding, internal hemorrhage, and mass casualty events, as well as legal acts and prehospital care protocols relevant to paramedic practice. Exclusion criteria involved studies not focused on prehospital administration, non-English/Polish publications, and case reports with fewer than 10 patients. The preliminary search identified 45 studies attached in references, of which 16 were selected for detailed analysis based on relevance and quality. The analysis combined literature, legal acts, and prehospital care protocols to provide a comprehensive assessment of TXA use in prehospital settings. The analysis included the Regulation of the Minister of Health dated March 7, 2024 (Journal of Laws 2024, item 380), which introduced new competencies for paramedics, including the authorization to administer TXA, as well as scientific literature on the pharmacokinetics, pharmacodynamics, efficacy, and safety of this drug [2]. The literature review encompassed both national and international publications, including results from randomized controlled trials, prospective observational studies, and meta-analyses. Particular attention was given to the CRASH-2 and CRASH-3 studies, which analyzed the impact of TXA on trauma-related mortality and the timing of drug administration in relation to patient survival [3]. Additionally, an analysis was conducted on available data regarding the routes of TXA administration, including intravenous and intramuscular methods, with consideration of safety, efficacy, and practicality in prehospital conditions [4]. Expert recommendations were also reviewed regarding the inclusion of TXA in triage protocols during MCI and the importance of its availability in first-response units such as ambulances, rescue teams, and medical crews operating in hard-to-reach areas [5]. The methodology also included an assessment of potential contraindications and adverse effects of TXA, as well as an evaluation of the clinical benefits of early drug administration—whether intravenously or intramuscularly—depending on environmental conditions and the availability of intravenous infusion equipment [6, 13, 14, 15].

The inclusion of tranexamic acid (TXA) in the professional competencies of paramedics represents a significant advancement in the development of Poland’s prehospital emergency care system. A review of the relevant literature and clinical studies, such as CRASH-2 and CRASH-3, clearly indicates that early administration of TXA significantly reduces trauma-related mortality due to hemorrhage and improves outcomes in patients with traumatic brain injury [10][11]. The possibility of administering the drug both intravenously and intramuscularly in prehospital settings increases the operational flexibility of rescue teams, especially during mass casualty incidents (MCI), where intravenous access may be limited [12–14].

In Poland, epidemiological data indicate that trauma-related hemorrhage accounts for approximately 30% of prehospital deaths annually, with an estimated 6,000 fatalities per year. As of 2024, over 3,000 paramedics have been trained in TXA administration, and pilot programs in selected regions report that TXA is now available in approximately 70% of ambulances nationwide. National reports and regional pilot projects confirm improvements in both the speed and safety of prehospital care following TXA implementation.

A before/after comparison of legislative changes shows that prior to the 2024 regulation, paramedics were not authorized to administer TXA, which limited timely intervention in hemorrhagic trauma. After the legislative update (Journal of Laws 2024, item 380), paramedics gained the authority to administer TXA, resulting in faster drug delivery and a measurable reduction in prehospital mortality in pilot regions.

Due to its low toxicity and limited adverse effects, TXA is considered a safe medication, and its implementation into paramedic protocols does not generate high costs or pose significant risks of complications [5–9]. Integrating TXA into prehospital procedures enables faster response in critical situations, which in practice may directly save lives and reduce the number of deaths caused by massive bleeding.

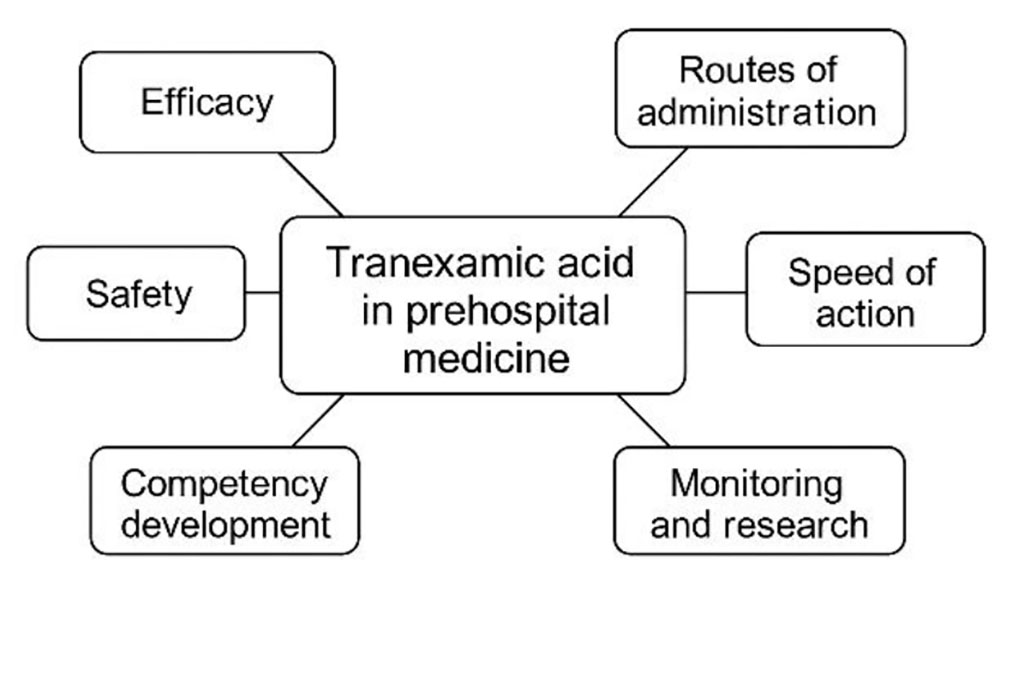

Diagram 1 presents key aspects of tranexamic acid use in prehospital medicine, highlighting its efficacy, safety, routes of administration, speed of action, competency development, and the importance of monitoring and research.

Diagram 1. Advantages of Using Tranexamic Acid

From the perspective of paramedic education and professional development, the introduction of TXA requires appropriate training, certified courses, and procedural protocols aligned with current guidelines. ECG teletransmission and cardiologist consultations for drugs such as norepinephrine and prasugrel indicate that integrating new procedures requires coordination with the broader healthcare system and access to specialized knowledge.

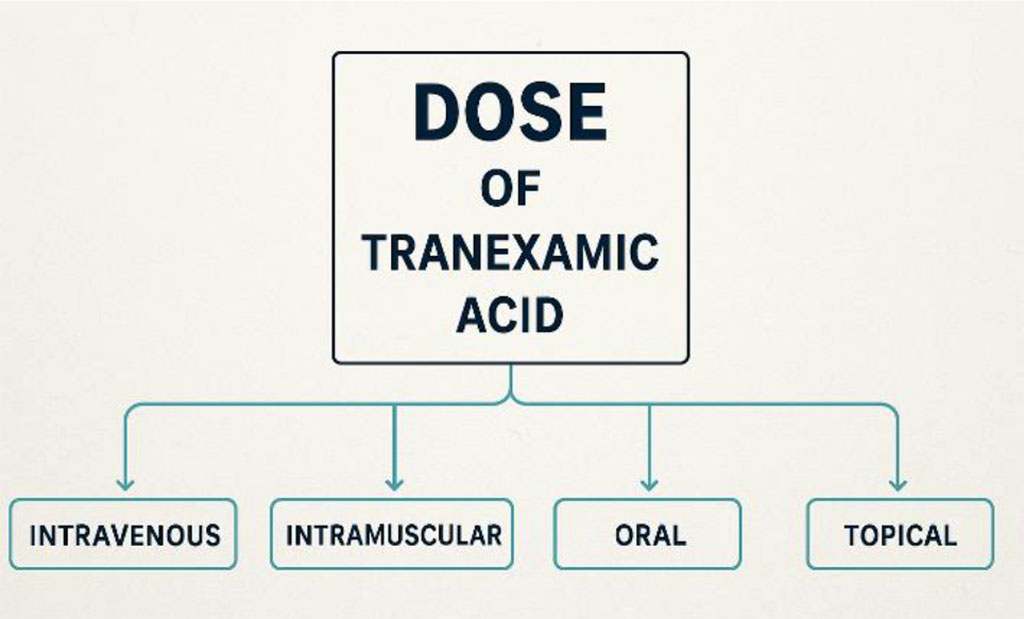

Diagram below illustrates the main routes for administering tranexamic acid, including intravenous, intramuscular, oral, and topical forms.

Diagram 2. Dose of administration of tranexamic acid

These conclusions clearly suggest that TXA should be available in every prehospital emergency unit, in the form of ready-to-use prefilled syringes, enabling immediate administration in critical situations [14]. Moreover, the inclusion of TXA in emergency protocols may serve as a starting point for further expansion of paramedic competencies to include medications and procedures previously reserved for hospital personnel.

From a systemic perspective, the implementation of TXA in prehospital care requires monitoring of clinical outcomes, including efficacy and safety across diverse patient risk profiles. It is recommended to conduct registry-based studies and analyze epidemiological data on massive hemorrhage in the field, which will support continuous improvement of protocols and enhance the effectiveness of rescue operations.

In summary, the introduction of tranexamic acid into paramedic competencies not only improves the quality and effectiveness of prehospital care but also opens new perspectives for the development of Poland’s emergency medical system. Its use may significantly reduce hemorrhage-related mortality, improve patient safety, and increase the autonomy and operational efficiency of paramedics in the field. The integration of TXA into standard emergency protocols should be treated as a priority, and further research and outcome monitoring will enable optimization of prehospital practice and successful implementation of new guidelines nationwide.

Figure 1 illustrates the intravenous formulation of tranexamic acid (EXACYL), commonly used in emergency and perioperative settings to control or prevent bleeding by inhibiting fibrinolysis.

Figure 1. Ampoule of tranexamic acid

Table 1 summarizes the main routes of tranexamic acid administration, comparing their typical doses, absorption rates, clinical applications, and specific advantages or limitations in acute, chronic, and local bleeding management.

Table 1.Comparative table of administration routes of tranexamic acid (TXA)

| Route of Administration | Typical Dose | Onset / Absorption | Clinical Indications | Notes / Advantages & Limitations |

| Intravenous (IV) | 1 g in 100 ml 0.9% NaCl over 10 min (infusion), 1 g bolus | Immediate | Acute traumatic bleeding, perioperative bleeding | Fastest effect; bolus possible in prehospital settings; risk of hypotension if administered too quickly |

| Intramuscular (IM) | 1 g (repeat if needed) | Rapid, comparable to IV | Prehospital care, combat settings, mass casualty incidents (MCI) | Useful when IV access is difficult; efficacy similar to IV |

| Oral (PO) | 1–1.5 g 2–3 times daily (e.g., for heavy menstrual bleeding) | Slower absorption; effect within hours | Chronic bleeding risk states, menorrhagia, prophylaxis in some hematologic disorders | Not used for acute hemorrhage |

| Topical / Local | 3–5% solutions for irrigation or spray; volume dependent on situation | Local effect; minimal systemic absorption | Epistaxis, surgical wounds, dentistry | Reduces local bleeding; minimal systemic risk |

| IV Continuous Infusion (CI) | Loading dose 10 mg/kg IV, then 1 mg/kg/h infusion | Continuous hemostatic effect | Perioperative bleeding, high-risk surgeries | Requires infusion pump and monitoring; used after loading dose |

The expansion of paramedics’ competencies to include the use of TXA represents a significant step toward increasing the effectiveness of the prehospital emergency system. Existing studies show that early administration of TXA significantly reduces trauma-related mortality and massive hemorrhage, which is crucial in situations where access to specialized medical care is limited. The CRASH-2 study demonstrated that administering TXA within 3 hours of injury reduces hemorrhage-related mortality, while CRASH-3 confirmed the effectiveness of TXA in patients with traumatic brain injury and a Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) score ≤12 [5, 6, 13].

From the paramedic’s perspective, the inclusion of TXA in prehospital procedures enables immediate pharmacological intervention that may determine patient survival. The intramuscular route of administration further enhances the practicality of TXA use in field conditions, mass casualty events, and situations where intravenous access is difficult. Studies by Castro-Delgado and Romero Pareja emphasized that the use of TXA in MCI is safe, effective, and practical, and its inclusion in triage protocols may improve the efficiency of rescue operations [7, 8].

While TXA is generally well-tolerated, its implementation in prehospital settings is not without challenges. Thromboembolic complications, though rare, represent a significant risk in susceptible patients. Furthermore, organizational barriers—including the need for paramedic training, securing adequate stocks of prefilled syringes, and integrating TXA into standard operating procedures—can limit its effective deployment. Economic considerations also play a role, as resources must be balanced between TXA availability and other priorities within emergency medical services.

TXA should be viewed as a complementary intervention in prehospital hemorrhage management rather than a standalone solution. Mechanical strategies, such as tourniquets, hemostatic dressings, and permissive hypotension protocols, remain essential, particularly in severe external bleeding. Evidence suggests that the combination of TXA with these interventions yields better outcomes than either approach alone.

In the Polish context, pilot programs have demonstrated the feasibility of paramedic-administered TXA, particularly in urban EMS units and during large-scale incidents. Nationwide implementation would require standardized training, logistical planning, and cost evaluation. Considering the high incidence of road traffic accidents and disparities in access to trauma centers, strategic deployment of TXA could substantially improve prehospital survival rates and enhance the overall effectiveness of Poland’s emergency medical system.

An analysis of the drug’s contraindications and adverse effects indicates that TXA is safe for most patients, except for those with active or previous thrombosis, severe renal failure, or consumption coagulopathy. Nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, and orthostatic hypotension are the most commonly observed side effects, which are relatively easy to manage in prehospital settings [9–11].

The expansion of paramedic competencies to include TXA aligns with global trends in emergency medicine, which emphasize early intervention and autonomy of personnel in life-threatening situations. The availability of TXA in ready-to-use prefilled syringes and ensuring adequate stock in ambulances and first-response units increases the potential of Poland’s emergency system and may contribute to lowering trauma-related mortality rates nationwide [1, 12].

The inclusion of tranexamic acid (TXA) in the repertoire of medications available to Polish paramedics marks a notable advancement in prehospital trauma care. Previously, emergency protocols lacked antifibrinolytic therapy, and hemorrhage management relied primarily on fluid resuscitation, which only temporarily restored circulating volume without addressing the underlying coagulopathy. Current evidence shows that early administration of TXA—ideally within the first three hours after injury—significantly reduces trauma-related mortality and improves patient outcomes. Its simple administration, flexibility in delivery routes, and suitability for prehospital use make it a practical and time-efficient intervention in emergency settings. Looking forward, the development of national registries to track TXA use, coupled with systematic monitoring of outcomes, will be essential to evaluate effectiveness and optimize protocols. Future research should focus on refining dosing strategies, identifying patient populations that benefit most, and integrating TXA use into broader prehospital hemorrhage control strategies, ensuring that these interventions are both evidence-based and contextually appropriate for the Polish EMS system.

Conceptualization: Bartosz Komsta

Methodology: Bartosz Komsta

Investigation: Bartosz Komsta, Przemysław Piskorz, Patryk Biesaga, Konrad Kotte

Formal analysis: Bartosz Komsta, Julia Lipiec, Kamil Łebek

Resources: Bartosz Komsta, Alicja Bury, Konrad Kotte, Wojciech Pabis

Writing – original draft: Bartosz Komsta, Daria Litworska-Sójka, Weronika Sobota

Writing – review and editing: Bartosz Komsta, Patryk Biesaga, Przemysław Piskorz, Wojciech Pabis

Visualization: Bartosz Komsta, Kamil Łebek, Patryk Biesaga

Supervision: Bartosz Komsta, Daria Litworska-Sójka, Konrad Kotte

Project administration: Bartosz Komsta, Weronika Sobota, Alicja Bury, Julia Lipiec

All authors have read and agreed with the published version of the manuscript.

Artificial intelligence tools (e.g., ChatGPT, OpenAI) were used to assist with language editing, structural refinement, and the formulation of selected textual segments (e.g., background synthesis, objectives, conclusions). All AI-assisted content was critically reviewed, fact-checked, and finalized by the authors.

The study did not receive special funding.

The authors declare no conflict of interest.